Atlanta Campaign National Historic Site was established by order of the Secretary of the Interior on October 13, 1944. Less than six years later, Congress transferred the components, five marker-and-picnic pavilion sites along the historic Dixie Highway, to the state of Georgia. Interestingly, one of the Atlanta Campaign markers commemorates a strategically significant non-event.

The Atlanta Campaign, which yielded a Union victory at a critical time (the capture of Atlanta in September 1864), was unquestionably a monumentally important episode in the Civil War. Accordingly, it has been commemorated by……. well, a whole bunch of monuments.

This site offers a virtual tour of the Atlanta Campaign with excellent photos and discussion. William Scaife’s award-winning book The Campaign for Atlanta is the basic reference for the campaign. Another excellent accompaniment is Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, Volume 2, November 1863-June 1865 by Union general Jacob Dolson Cox (available in ebook format). If you prefer a simple, tightly written chronology, visit this site.

Historic sites associated with the Atlanta Campaign sites are – or if developed and promoted the right way, could be – important tourist attractions. They could get motorists to stop and bide a while at places where they might not otherwise do so. Once enticed to stop, these tourists might be parted from some of their money, creating economic benefits for the host communities.

It was these thoughts, more than historic resource preservation per se, that led the 1930s-era Works Progress Administration (renamed Work Projects Administration in 1939) to cooperate with the National Park Service in creating five Atlanta Campaign interpretive picnic pavilions or "pocket parks" along the historic Dixie Highway in north Georgia.

The Dixie Highway, constructed during 1915-1927, was the main route from the Midwest to Florida until Interstate 75 was built. Many historians consider the Dixie to be America’s first true interstate highway. All along the Dixie, communities offered tourist services. At first, amenities such as tent camps and roadside picnic pavilions were offered free of charge. Later, as tourist traffic increased, the route blossomed with tourist courts, cabins, inns, and motels with adjacent restaurants, diners, hot dog stands, filling stations, and roadside markets.

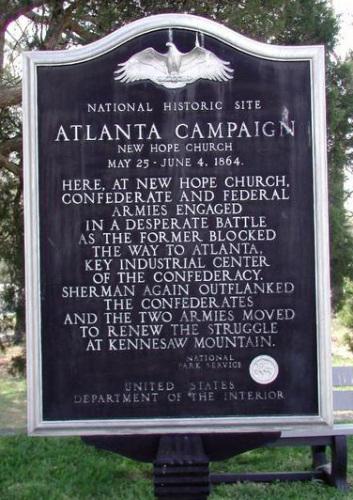

The WPA’s five pocket parks are at Rocky Face Ridge (at the state highway patrol post); Resaca. which was the first major battle of the Atlanta Campaign; Ringgold (Ringgold Gap); New Hope Church, and Cassville.

Perhaps the most intriguing of the WPA's Atlanta Campaign pocket parks on the Dixie Highway (modern U.S. 41) is the one in Cassville. In Civil War times, Cassville was a railroad, trade, and educational center (two colleges) that functioned as the cultural capital of North Georgia. Though small (peak population ca. 1,300), Cassville was one of the most important population centers between Nashville and Savannah.

Cassville’s roadside marker, which is actually on Cassville Road just off U.S. 41, reads as follows:

National Historic Site

Atlanta CampaignCassville

ON MAY 19, 1864, JOHNSTON ENTRENCHED ON THE RIDGE EAST OF THIS MARKER PLANNED TO GIVE BATTLE BUT SHERMAN THREATENED HIS FLANK AND HIS CORPS COMMANDERS OBJECTED TO THE POSITION.

HE THEREFORE WITHDREW TO ALLATOONA PASS. RATHER THAN ATTACK THIS STRONG POSITION, SHERMAN MOVED PAST IT TOWARD NEW HOPE CHURCH.

Yes, you read it correctly; on 19 May 1864 an important non-event happened at Cassville, Georgia. There very well could have been a big, bloody, really important battle at Cassville in May 1864, but there wasn’t. What has come to be called the “Cassville Affair” was, from the tourist attraction standpoint, a near miss for Cassville.

When the Secretary of the Interior issued an order on October 13, 1944, instructing the National Park Service to administer the Atlanta Campaign National Historic Site, it could scarcely have been an occasion for an NPS celebration (not to mention that World War II was raging at the time). You’d have to have been at least one full bubble off plumb to really believe that a scattered collection of interpretive picnic pavilions belonged in the National Park System, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Yellowstone National Park and Gettysburg National Military Park.

What does the federal government do with a property like this? Just what you think it does. On September 21, 1950, Congress abolished the Atlanta Campaign NHS and transferred ownership to the state of Georgia.

In fairness to Cassville, I must say that it possesses a good bit of interest for genuine history buffs. Civil War-wise, the most interesting thing to see in Cassville is not the roadside marker. It’s historic Cass Station, the ruins of which stand beside the old Western and Atlantic Railroad track a stone’s throw from the burned-out shell of an old cotton warehouse.

Because of its strategic location between Atlanta and Chattanooga, Cassville was a vital link in the Confederacy’s rail infrastructure. It was a foregone conclusion that Sherman’s troops would end up in Cassville and at Cass Station, because Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign basically followed the W&A tracks into the city of Atlanta. Here is what Sherman had to say about the W & A after the war:

The W&A RR of Georgia should be the pride of every true American because by reason of its existence the Union was saved. Every foot of it should be sacred ground, because it was once moistened with patriotic blood. Over a hundred miles of it was fought in a continuous battle of 120 days, during which, night and day, were heard the continuous boom of cannon and the sharp crack of the rifle.

True Civil War history fanatics know that Cass Station even played a role, if rather minor, in the Great Locomotive Chase of April 12, 1862. Ill-fated civilian spy James Andrews stopped there to get water and wood for The General, the locomotive he and his band of 22 civilian-disguised Army soldiers had stolen. Andrews even obtained a train schedule from the stationmaster while he was at it.

After General Joseph Johnston pulled his Confederate troops out of Cassville, Union forces moved in and controlled the town for more than five months. They did not treat it kindly, either, eventually putting it to the torch. On November 5, 1864, Cass Station, along with most of the town, was destroyed by the Fifth Ohio Cavalry in retaliation for guerrilla activity in the area.

By the end of the war, all that remained of Cassville was three homes, two churches, and a Confederate Cemetery. No official records, photographs, or other documents survived. It’s a major understatement to say that Cassville never regained its former status as the cultural center of north Georgia.

Post script: The Dixie Highway stretched from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan on the Canadian border all the way to Miami. Part of the route, U.S. 23 then and now, passed near my childhood home in Bay City, Michigan. While in high school I worked part-time in a full-service gas station (the only kind there were back then) situated on U.S. 23. There I would occasionally chat with people who had driven the Dixie Highway all the way to Florida. Imagine that! This was in the pre-Interstate highway era, and if a person drove all the way to Florida from Michigan he was a by-gosh real tourist with the bragging rights attendant therewith.

I must admit that I have mixed feelings about the Dixie Highway. In June 1961, while driving in a blinding rainstorm on the Dixie near Detroit, I lost control of my car (a 1956 Chevrolet Bellaire I had owned for just three days) and ended up skidding backwards into opposing traffic. Nobody was hurt in the ensuing three-car crash -- a miracle, considering we didn’t have seat belts back then -- but I got an object lesson in several laws of physics and subsequently spent a good deal of time and money replacing sheet metal on my mangled Chevy. Since I had money enough to buy only vital parts, and none at all for a paint job, the result was an auto that was challenging to drive (being difficult to steer and stop) and had a very distinctive appearance (being turquoise overall, but completely white forward of the passenger compartment).

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment