Editor's note: Across the country, there are many spectacular landscapes that would fit appropriately within the National Park System. This article is the latest in an occasional series that looks at some of these places.

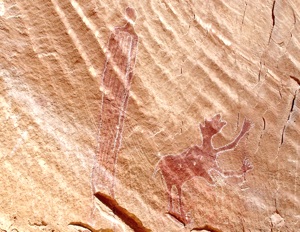

In places, the brush strokes are delicate, exquisitely formed, the work of a master. Others, though, are more roughly fashioned, in some cases pecked or scratched into the rock face's thin veneer.

The images, dating back thousands of years, are priceless. So, too, is the scenery in the landscape within which these pictographs and petroglyphs exist. It is a landscape of staggering natural beauty expressed by soaring cliffs, canyons compared to the grandest one in the country, minarets, and reefs of rock that tell a fascinating geologic story.

The plein aire art museum where you can find these works? Central Utah's San Rafael Swell.

Near-Perfect Preservation Conditions

The general aridness of central Utah gets the credit for preserving the rock art forms that, perhaps, date back 7,000 years, and which have been referred to as the state's Sistine Chapel. Though some appear childish, and others have been covered with images from nomadic cultures that followed the original artists through the millennia, the figures tell intriguing, at times hard-to-cipher, stories that still beg explanation.

The images inspired some intriguing names: "Head of Sinbad" was attached to a figure topped by a wriggling snake, while "Black Dragon" was spawned by a pictograph that some think looks much like a winged dragon.

Some of the oldest images fall under the category of "Barrier Canyon" rock art, a folder Dr. Polly Schaafsma, one of the country's most-renowned experts on Native American rock art, assigned the images to in the 1960s when she was part of an effort to catalog what existed in the southern Utah canyons that the pending Lake Powell were about to inundate.

Rock art at Buckhorn Wash in the Swell. Photo courtesy of Emery Country Travel Bureau.

While researching a story for Smithsonian magazine some years ago, I learned that some archaeologists who have studied the Barrier Canyon images believe they were created between 1900 B.C.and A.D. 300. But Alan Watchman, a research fellow at Australian National University, told me his radiocarbon analysis dates some of them to the Early Archaic period, from about 7430 B.C. to 5260 B.C.

Another archaeologist, Phil Geib, also was of the opinion that the earliest image might date to the Archaic period of roughly 8,000 B.C. to 1,000 B.C. He notes that a figurine similar in style to Barrier Canyon rock art was recovered in a cave in Utah above a layer of soil dating to around 7500 B.C. A distinctive style of sandals directly associated with the figurine, he says, dates to around 5400 B.C.

While some Barrier Canyon images can be found in Canyonlands National Park, as well as Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, the San Rafael Swell is rife with them. Though many are not easily found.

But Archaic-era images aren't the only ones within the Swell. There are some from the Fremont Culture that lived in the area from about 700 A.D. to 1300 A.D., and more recent images crafted by Ute artists and Spanish explorers, and even an inscribed name purportedly made by that 19th Century criminal, Butch Cassidy.

More modern history counts structures and roads built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, overly ambitious ranchers trying to coax a living from the spare landscape, remnants of uranium mines tapped during the Cold War.

Taken together, this history -- modern and prehistory -- tell wondrous stories in a demanding landscape.

Spectacular Landscape

Surrounding this graphic history is a landscape that is jaw-dropping.

Within the Swell you'll find some spectacular scenery thanks to its underlying geology. Photo via Big Stock Photo.

The San Rafael Swell is an 80-mile by 30-mile bulbous protuberance of rock in south-central Utah that was ratcheted into place by geologic machinations some 60 million years ago. The resulting geology is an open-air classroom, a layer-cake of strata named Coconino Sandstone, Kaibab Limestone, the Triassic Age Moenkopi and Chinle Formations, Wingate, Kayenta, and Navajo Sandstones.

These rockbeds deposited over millions of years have colored the Swell with buffs, reds, tans, greys, blues, yellows, whites, and oranges. And within some of those formations are paleontological treasures -- the Cleveland Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, which holds a rich cache of fossilized prey and predator dinosaur remains, lies near the northern end of the Swell, and field research elsewhere in the Swell has turned up amazing finds.

According to the Utah Geological Survey, remains of Acrocanthosaurus, a giant carnivore of the Early Cretaceous that was nearly as large as Tyrannosaurus, turned up in the Cedar Mountain Formation not far from Cleveland Lloyd. It possessed "enormous teeth adapted for cutting flesh," the Geological Survey notes.

As the landscape rose, it was transformed into a maze of sorts by erosion. So cut, twisted, and inhospitable appearing is the Swell that when mountain man Jedediah Smith peered into it briefly in 1826, he figured there was no reason to explore it further and kept on going. What the mountain man found to be a barren wasteland is viewed to many today as spectacular.

Rock art in Black Dragon Canyon. Photo courtesy of Emery County Travel Bureau.

It was back in 1935 that many Utahans felt the same way, and at the time the Utah State Planning Board briefly lobbied for creation of a "Wayne Wonderland" national park, a 360,000-acre park named after Wayne County, one of the counties that the Swell is found in.

In 1936 Bob Marshall, founder of The Wilderness Society, identified nearly 2 million acres of roadless area in the general vicinity of the Swell that should be protected, and in 1980 the Interior Department identified seven potential National Natural Landmark sites in the same area. More recently, the Emery County Development Council at one point proposed that 210,000 acres of the Swell be set aside as a national park. About in the early 2000s, then-Gov. Mike Leavitt proposed that 620,000 acres be set aside as a national monument.

But the movement never could gain traction in Utah, where 67 percent of the landscape is owned by the federal government, a percentage that in the state's political circles spurs contempt.

Today part of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management landscape, the San Rafael Swell might not carry the "national park" imprimatur as do nearby Capitol Reef and Canyonlands national parks, but it is no less worthy of tag. Those who believe the Swell needs greater protection, perhaps as a unit of the National Park System or else as officially designated wilderness (it currently contains seven Wilderness Study Areas), cite mining, grazing, and off-road vehicle impacts as threats to the landscape. Some rock art panels have served as shooting targets.

Recreational Opportunities Abound

But the lack of a more protective land-management status hasn't prevented recreation in the Swell. Indeed, near the southern end of the Swell stands Goblin Valley State Park, and on BLM lands nearby the beautifully eroded Little Wildhorse and Bell slot canyons wiggle through the Swell.

Along with designated ORV routes, the Swell offers endless miles for horseback use, backpacking edens, mountain biking, and a river -- the San Rafael -- popular with paddlers when runoff swells it, usually from May into mid-June, depending on the previous winter's snowpack. The Green River, which runs through a portion of the Swell, is much more reliable for white-water cowboys and cowgirls looking to buck the rapids.

There's a wonderful BLM campground near the brink of the Wedge Overlook, which looks over a jagged canyon nearly 1,000 feet deep and which is locally referred to as the Little Grand Canyon.

Rock art aficionados appreciate the Swell for being home to some of the Southwest's most curious rock art, such as the renowned Buckhorn Wash Panel, the Head of Sinbad images, the Rochester Panel, or the collection of images found in Black Dragon Canyon.

Venture into the Swell and you'll find buttes and mesas, stone arches and minarets, grassy meadows and box canyons, streams and springs, and possibly be able to retrace routes Butch Cassidy took while fleeing posses. Too, the Swell is home to more than 200 desert bighorn sheep, peregrine falcons, feral horses and burros, Bald and Golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, and prairie falcons.

The prominence of the Swell -- its landscapes and rich archaeological and paleontological resources -- came up when the Obama administration was considering prospective landscapes for protection under the Antiquities Act. That Act allows presidents, without congressional approval, to designate landscapes for protection as national monuments.

"... the San Rafael Swell is a .. . giant dome made of sandstone, shale and limestone -- one of the most spectactular displays of geology in the country. The Swell is surrounded by canyons, gorges, mesas and buttes, and is home to eight rare plant species, desert bighorns, coyotes, bobcats, cottontail rabbits, badgers, gray and kit fox, and the golden eagle," reads an internal draft document prepared for Interior Department officials.

"Visitors to the area can find ancient Indian rock art and explore a landscape with geographic features resembling those found on Mars."

While political push-back from Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives seems to have squelched the administration's consideration of the Swell, and any other landscapes, for protection as national monuments, it hasn't lessened any of the wonders that you'll find in the Swell.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The Swell is in the top 5 of my favorite places to wander. I think BLM is doing a good job managing the area, especially considering that they barely get any money to do it.

If anything, the SRS should be designated as a National Monument and left to BLM to manage like GSENM. Or just designate the wilderness areas once and for all, though we all know the Utah Congressional delegation will never let that happen.

The SRS might make President's Obama's monument list in January, 2017 if he's reelected. But most folks I know this it's okay just like it is now. I tend to agree with them.

Kurt, thanks for a comprehensive story that obviously required a whole lot of work. But this is Utah -- and there's COAL and maybe OIL beneath that beauty.

Remember Utah's environmental motto: Multiply, multiply and pillage the earth.

Tha San Rafael Swell is magnificant and it would be a disgrace if anyone was ever allowed to ruin it's majasty.

That said, this world needs habitat for rare plants and animals set asside permenantly right now. Ancient trees and lots of them, whole forests, millions of acres, to protect species that are endangered right now, in harms way, living on land that will be exploited and divided into islands of habitat that will not function as whole forests do.

The whole Earth will benifit from protected forests and the oxygen they give us, the clean water they provide.

The San Rafael Swell is magnificant, but there's not much oxygen or water being made there.

The Tongas, the Maine Woods, the Klamath Siskiyou Forests are endangered right now, and they are as essential to life on Earth as the Amazon. Don't overlook necessity and the emmense beauty of vast forests while, by it's sheer desolation, the San Rafael desert protects itself.

www.ancientforestnationalpark.org

Lee - I recent took a trip which had me cross Utah twice - 70 to 15 to 80 going west and then Route 50 (named the Loneliest Highway in the US) going east. Some years back I also took the southern route through Four Corners. I didn't see an oil or gas rig, coal mine or "pillaging" of any kind on all three legs. Heck the only civilization was in the Provo/Salt Lake City corridor. I have traveled to nearly every state in the union and Utah is one of (if not) the least developed or exploited in the country. Your whining has no basis.

Driving through a state hardly constitutes any form of evidence of a state's development of it's land. This could mean that you are unobservant, that Utah makes new dirt roads away from highways to build oil and gas rigs, and many other possibilities. Most other states also don't have places like Zions, Canyonlands, Bryce, and Capitol Reef, whose fragile landscapes are easily destroyed but not easily mended. No basis? Think again

I've certainly been through Utah a few times. It's actually pretty hard to miss all the mining going on there. I remember going from SLC to Price (where we stayed overnight) and then to Moab. I would have thought it would have been pretty hard to miss all the open pit mines. At the Holiday Inn in Price, there were people in the lobby openly going over mine plans. We also went to a local store for supplies, and the local BLM mining office was right there.

Anon, I suggest you try living in Utah and listen to some of the nonsense that comes from our loonislature and their development buddies.

As for mining evidence visible from the Interstates, you'll only need to drive a few miles off any of them to find all you want. And if you did indeed drive through the Four Corners area off any of the main roads, you had to have been driving with your eyes closed. (How on earth do you that?)

Your claims have no basis because you simply haven't taken the time to investigate very carefully at all.

Lee, If you drive for an hour or two and don't see a single structure on the state's two major highways and you think your state is being pillaged? You are the one driving blind. Oh, that's right, you don't drive because that would use products from evil "big oil".

It has been 10-15 years since I did the Four Corners route, perhaps things have changed there but there certainly was no pillaging when I was there. Next to Nevada, Utah would appear to be one of the least developed states in the country