A creekbed that carries water intermittently through Canyonlands National Park is also a road that should be open to vehicles. At least that's the argument the state of Utah will press this week when its attorneys appear before the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The state and one of its counties hope to convince the panel that Salt Creek is a road, an argument they failed to sell to a federal court judge more than a year ago. When he disagreed with their position, Judge Bruce Jenkins wrote that, "a Jeep trail on a creek bed with its shifting sands and intermittent floods is a by-way, but not a highway."

How the 10th Circuit receives the state's arguments is highly important for national parks, as Judge Jenkins' opinon ran a stake through arguments that abandoned Jeep tracks, cattle trails, and even creek beds are legal thorofares under R.S. 2477, a Civil War-era statute initially created to further western expansion.

In 1976 Congress repealed the law, but not before providing that any valid R.S. 2477 route existing at the time of the repeal could continue in use. Since then, there have been many debates and many lawsuits over what constituted a valid R.S. 2477 route.

Utah just might be the champion of R.S. 2477 challenges. According to Ted Zukoski, a staff attorney with Earthjustice, "Salt Creek is just the first domino the state hopes will fall to its extreme interpretation of law. Utah earlier this year filed 22 lawsuits aiming to take control of 10,000+ more "highways" - including streambeds, little used two-tracks and slot canyons - many in national parks, designated wilderness, or national monuments."

"The state's lawyers have essentially asked the Court of Appeals to rule that any hiking trail or wagon track that was used by one or two people a few times over a 10-year period is a 'constructed highway' that the state can control," Mr. Zukoski wrote in a column last week for Earthjustice's blog. "In essence, the state is hoping to turn a repealed, 140-year-old law meant to shield public investments in real highways into a sword to destroy wilderness.

"By gaining control of such 'highways,' the state could effectively tie the hands of park rangers and other land managers so they wouldn't be able to protect the land, wildlife, or watersheds inside a national park from the destructive impacts of motor vehicle."

There long have been pockets of disgust over federal land ownership in the West, and perhaps nowhere is that stronger than in Utah, where roughly two-thirds of the landscape is federally managed. While the "Sagebrush Rebellion" mightily reared its head some three decades ago, its waning vestiges were on trial before Judge Jenkins.

The poster child of the rebellion rose up on July 4, 1980, when several hundred people gathered in Moab, Utah, on the doorstep of both Canyonlands and Arches national parks, to celebrate the nation's birthday...and decry federal land-management policies. From atop a Caterpillar bulldozer, one carrying a few "Sagebrush Rebel" stickers and spouting a U.S. flag from its smokestack, county officials complained about federal land managers. After firing up the crowd, the politicians fired up the bulldozer and, while following the scant traces of an abandoned mining road, worked to scrape a path into a nearby Wilderness Study Area on U.S. Bureau of Land Management lands.

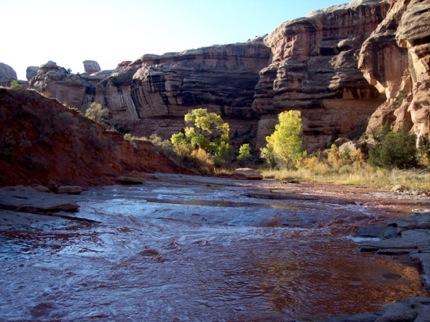

Litigation, not bulldozers, has littered the landscape in Canyonlands these past dozen years over whether Salt Creek should be open to off-road vehicles. Born from springs and snowmelt on the Abajo Mountains just about 5 miles the south of the national park, the meandering creek is most vibrant during flash floods that scour the streambed. For the rest of the year, its thin flow depends largely on the output of occasional springs and storms. When enough water fills the creek, it slowly makes its way 32 miles to the Colorado River.

Salt Creek is a portal to the past, a vital one at that for both biological resources and archaeological records. Its water nourishes a surprisingly rich riparian habitat in this largely arid national park, and "supports the park’s richest assemblage of birds and other vertebrate wildlife outside the Green and Colorado river corridors," according to the federal government.

This week's hearing before the 10th Circuit will be held on Wednesday. It could be months, though, before the panel rules. Stay tuned.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

I truly believe that Salt Creek should remain closed to off road vehicles both from an environmental and an ecological point of view. We love back roadinig as much as any one but it is not like there aren't already enough trails to go on.

Sincerely, Guy O. Parks

This is a national park. This is why these parks need federal protection from predator state politicians. They won't be really happy until there are gas and oil wells there, or everything is just dug up for fracking.

Thats right, there aren't any predator federal politicians.

Maybe, but that doesn't mean there aren't state ones.

This is just one more symptom of a much wider problem in Utah. Our legislature is bent on "retaking Utah" from the Feds. They seek virtually any excuse to try.

I just came home from an extensive trip throughout southeastern Utah and southwestern Colorado. My GPS tried to direct me along "roads" that obviously have not carried a wheel -- or horse, for that matter -- in a long, long time. But, according to the loonislators, those are still roads.

Then there were a few San Juan County roadsigns that ostensibly marked a "road" where no trace whatsoever could be seen.

This despite the fact that judging solely by the number of out-of-state license plates I saw on roads (real roads, that is) along the way, the vast majority of traffic down there -- and probably a very large percentage of local income -- comes from people here to enjoy the scenery and breathtaking spectacles of Utah.

One spectacle: An old practice of gouging tourists that is still alive and well in Blanding. I stopped for gas at a station on the Ute Reservation about 15 miles south of Blanding where I paid $3.79 for a gallon. I had to go on to Blanding for some groceries, and discovered that the stations in town were charging $3.99. So I asked the young man at one of the stations if I would be eligible for a "local discount." He asked where I live and I told him I'm from northern Utah. "Yeah," he replied. "That's close enough." Thus, as a "local" I could have qualified for the 20 cent per gallon "local discount" because I was local enough to know to ask for it.

I went back to the Ute station on the way out to Natural Bridges and stopped to talk with the young native girl at the counter. She shook her head and said, "Yes. Disgusting isn't it? But at least we Indians are honest . . . "

Our local politicians constantly yowl about something called "Utah Values." Makes me wonder if price gouging is part of Free Enterprise. I guess it is. Another Utah Value must also be caveat emptor.