A proposal to create a 1.4-million-acre national monument wrapping Canyonlands National Park in Utah should not be dismissed out of hand, but receive serious consideration from the Obama administration. And it should receive equally serious consideration from Utah officials who promote the state's recreational wonders in one breath and demand a handover of federal lands in the next.

The current proposal for a Greater Canyonlands National Monument is not a move to "lock up" these lands, but rather seen as a way to provide for multiple recreational use and help smooth out economic bumps by bringing into the region tourist dollars, wealthy retirees, and "knowledge workers" who often can work from home.

Ashely Korenblat, who owns Western Spirit Cycling, a Moab, Utah, bike shop, said that under the proposal no Jeep routes or mountain bike trails would be closed. While the proposal envisions a ban on energy development, it also sees a sprawling national monument that would lure outdoor recreationalists of many stripes to southern Utah.

"We need the monument to protect the landscape that makes these roads and trails worth experiencing, and to keep us on the path of consistent and sustainable economic development that doesn’t rely on more speculative technologies or fluctuate with worldwide commodity prices," she says.

Utah's Branding As An Outdoor Recreational Capital

When you consider the idea, it actually goes hand-in-hand with the state government's approach to luring businesses. This is the state that long campaigned for a Winter Olympics, won the right to host the 2002 Games, and afterwards viewed and promoted itself as a winter sports capital for training and competitions.

Ogden, a short drive north of Salt Lake City, boasts that it "has become known around the globe for its high adventure recreation and high-energy outdoor lifestyle." Along the way towards building that description, the city persuaded Descente, DNA, Salomon, Suunto, Atomic, Goode Ski Technologies, Peregrine, Kahuna Creations, Scott USA, and Rossignol to relocate to Ogden. Goode officials say they moved to Ogden specifically to be within a short drive of both "world-class snow and water skiing."

Peter Metcalf, owner of Black Diamond Equipment, a gear-manufacturing company, relocated his business from California to the Salt Lake Valley specifically to be close to the climbing routes of the Wasatch Range and the canyoneering landscape farther south.

“We are here because of the inspiration and the creativity our employees derive from being here," he says.

Utah's ties with the outdoor recreation industry go back years, thanks to the twice-a-year Outdoor Retailer conventions held in Salt Lake City. These shows bring together gear manufacturers and retailers for multi-day get-togethers that leave behind some $42.5 million a year.

To further burnish Utah's reputation as a world-class destination for outdoor recreation, the Outdoor Industry Association and more than 100 recreation-oriented businesses from across the world last fall reached out to President Obama to use his powers under the Antiquities Act to create a 1.4-million-acre Greater Canyonlands National Monument.

The protection a monument would provide the landscape would be a step down from that provided through an expansion of the national park, and in that regard the proposal can be viewed as a compromise to those in Utah who view the federal landscape with distaste.

Completing Canyonlands

It's long been suggested that Canyonlands itself needs to be "completed." This tableau of red-rock country has never lived up to the expectations of those who set their eyes on the landscape and saw not a wasteland but rather a cataclysm of earth, water, and sky that should be protected and enjoyed as a national park.

As early as 1936, 28 years before Canyonlands was actually created, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes envisioned an "Escalante National Monument" of nearly 4.5 million acres, a behemoth that would encompass a good deal of Utah's southeastern corner south of Green River and east of Torrey. Not until the 1960s did the idea of a national park in this corner of Utah return, and it led, after much horse-trading, to a 257,000-acre Canyonlands National Park that was created in 1964.

But the creation of Canyonlands, which grew a bit through the years with the addition of the Horseshoe Canyon annex, didn't settle the debate over exactly how big the park should be. It was revived most recently in the late 1980s by the National Parks Conservation Association, and again in the early 1990s when then-Superintendent Walt Dabney endorsed "completing" the park by stretching its boundaries to the surrounding rims of the basin created by the Colorado and Green rivers.

But in highly conservative Utah, where there is a resentment over the federal government's land ownership because it is viewed as an impediment to economic development, the movement to enlarge Canyonlands has never gathered much steam.

There have been petitions in recent years to protect the "greater Canyonlands" region, and late last year the push took a bigger step when the OIA coalition promoted for the Greater Canyonlands monument a vast landscape of U.S. Bureau of Land Management lands running west from Canyonlands to Hanksville, south to wrap Natural Bridges National Monument, east to parallel U.S. 191, and north towards Interstate 70.

That proposal stirred much debate in and around Moab, Utah, the gateway to both Canyonlands and Arches national parks. So much debate that some of the businesses that signed on in support of the OIA proposal were tagged for a boycott on a Facebook page, Sagebrush Coalition.

Some opponents to the OIA proposal suggest that instead of asking President Obama to use his authority under the Antiquities Act to create such a monument, that an "upfront, full dialogue and discussion" of the proposal be held. Unfortunately, talk of designating national monuments is a nonstarter in Utah's current political makeup, where officials instead want the federal government to hand over public lands to the state.

The Facebook page against the proposal and against the Moab-area businesses in support of it demonstrates the lack of interest in considering the proposal. Plus, U.S. Rep. Rob Bishop, a Utah Republican who chairs the House subcommittee on national parks and public lands, likely isn't interested in discussing the matter, either. His work during the 112th Congress and his comments show he would rather see the federal government relinquish its holdings in the West.

What's At Stake

What's at stake in seriously considering a monument on the landscape adjacent to Canyonlands?

Mr. Bishop has long supported increased energy exploration on public lands in Utah, including tar sands development. Unfortunately, a recent NPR report on the pollution from such development in Alberta, Canada, demonstrates that this is anything but a clean industry, and the water it would take to develop in Utah, the second-most arid state in the nation, is troubling.

Too, what would be lost by allowing more energy development here? For starters, the raw beauty of the landscape would be at risk. Wildlife would suffer, too, from networks of oilfield roads. And what about the unknowns that inhabit the landscape. A long-running inventory of all species -- plant, animal, insect, fungi, fish, reptile, etc, etc, -- within Great Smoky Mountains National Park has turned up not only some 8,000 species previously unknown residents, but also more than 900 previously unknown to science.

What can be gained is not only protection of a wondrous landscape, but a strengthened regional economy, one not subject to energy booms and busts.

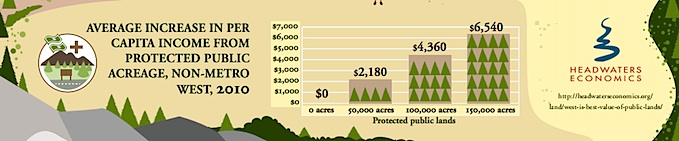

Studies show that protected federal lands help the local economies. Headwaters Economics graphic.

According to Headwaters Economics, an independent, nonpartisan research organization, "(P)er-capita income in Western non-metropolitan counties with protected public lands is higher than in other similar counties. For every gain of 10,000 acres of protected public land, per-capita income in that county in 2010 was on average $436 higher. So a county with 50,000 acres of protected public lands was $2,180 higher; while one with 100,000 acres of protected public lands would have a $4,360 higher per capita income in 2010. For perspective, that same year the average per capita income for non-metro Western counties was $34,870."

Further more, that study found that "from 1970 to 2010, Western non-metro counties with more than 30 percent of their land base in federal protected status increased jobs by 345 percent. As the share of federal lands in protected status goes down, the rate of job growth declines as well. Western non-metro counties with no protected federal land increased jobs by 83 percent."

To ignore these risks, and realities, would be a disservice not only to Utahns, but to all Americans.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Take another look at my posts. I do refer to the specific language of the Act (as do the courts).

To argue that this reading of the Act is somehow a "progressive" misreading is pretty odd, given that the Act has been invoked by conservative Presidents to create national monuments that consist of only natural elements.

Really? I don't see any reference in the Act to "natural elements". Can you please point those out?

By definition, if they have been so invoked, those Presidents were not being "conservative".

Take another look at my posts. You're confusing the terms of the Act and what things are covered by those terms.

Do I really need to point out the circular reasoning here?

Several areas in the Greater Canyonlands monument proposal would already have been designated as national parks or monuments all by themselves, if they had been anywhere but Utah. Three examples: Harts Draw, Bridger Jack Mesa, the Dirty Devil River and its side canyons. Their national values need protection as soon as possible.

protection from what?

I think you are making my point again. People after the fact have extended what is covered. If its not in the Act (and not part of the intent of the act) then it should be covered.

Hardly - its as linear as you can get. If you do something that isn't conservative, your not a conservative, no matter what you or anyone else wants to call you.

MikeG, let's protect it against any mineral or energy development. if you listen to those opposing the monument, some say they want mining and they want development of oil, gas and tar sands. Others say the monument's unnecessary because nothing is going to hurt the land. They don't agree among themselves. I say protect this area, and develop minerals and energy elsewhere, on lands that do not have the outstanding values of the Canyonlands. It's a matter of setting priorities.

ecbuck,

You seem to be historicizing the "intent" of the Act through a particular reading of it. If you read the phrase I've singled out above, nothing in the terms by definition excludes natural elements.