In 1877, a group of African-Americans arrived in northwestern Kansas. They had left Kentucky to escape the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and increased repression of blacks throughout the South. Expecting conditions to get much worse with the end of Reconstruction, they decided to make a new home on the western plains. They settled in a place they called Nicodemus.

Despite the isolation, the challenging climate, and the lack of good railroad connections, the community took root. Churches, stores, and gathering places served 600-700 people spread out across the Kansas countryside.

This was the first black homesteading community in the West. It thrived until the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression of the 1930s, when people started to move to the cities to look for work. Only a handful of people remain today, and only one of them is still farming. Even so, Nicodemus remains a real community. Many descendants of Nicodemus still return every summer for a large Homecoming event.

A Part Of The Park System

The National Park Service is charged with preserving the history here and telling its stories. Nicodemus National Historic Site became part of the National Park System in 1996, along with Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (Kansas) and Washita Battlefield National Historic Site (Oklahoma). Tallgrass Prairie and Washita Battlefield each have a new visitor center. Both of them look great.

Nicodemus does not really have a visitor center and it doesn’t look so great. Geography is part of the problem. Nicodemus is located in an out-of-the-way part of a sparsely-populated region. It’s about five hours from a commercial airport and at least an hour from the Interstate in Hays, Kansas. It attracts fewer than 3,000 visitors in most years.

It’s not surprising that the site lies at the bottom of the budgetary food chain. Politically, western Kansas is not a traditional friend of the federal government, so the NPS is prohibited from owning the land it needs. In addition, the people who live here have mixed feelings about tourists poking around their churches and homes. Adding park infrastructure here must be acceptable to the community that the site celebrates.

To top it off, Nicodemus lacks powerful advocates. Tallgrass Prairie National Reserve has support from a major environmental trust and a Texas billionaire, among others. Nicodemus has no such supporter.

Good Planning, But No Money

Though it doesn’t have facilities as nice as its sister parks, Nicodemus has had plenty of planning documents and reports: a Cultural Landscape Report in 2003, a General Management Plan in 2004, a Long-Range Interpretive Plan in 2009, and a Historic Resources Study in 2011. A student team from the City College of New York’s Landscape Architecture Program has also developed an award-winning plan for the site. They suggested moving much of the interpretation to the Internet and making virtual connections between Nicodemus and other places and themes. This virtual park is an innovative idea but it doesn’t solve the problem of what to do with the physical reality of Nicodemus.

There are some good ideas in all those plans, and they all point out the need for money and staff. Unfortunately, it seems that Congress and NPS budgeters would rather pay consultants to write reports than spend the money to follow up on their recommendations. These closed pocketbooks do a real disservice to the place. It may have lousy facilities, but Nicodemus has friendly staff who tells its stories well. The park tries to greet every visitor with a 15-minute orientation talk.

The ranger will meet you in the Township Hall, rented from the local government. The inside of the hall looks like a high-school auditorium. It’s used for many community events, so the exhibits are built to be moved out of the way when necessary. Visitors read signs on fold-up screens and watch a brief film on a television tucked over in one corner.

The immediate, personal service puts a nice gloss on the site, but the physical environment is woefully inadequate for both visitors and staff. It’s also understaffed, with only one ranger and one guide. If either of them get sick or take a vacation, the other has to do everything.

Five Buildings, But None To Tour

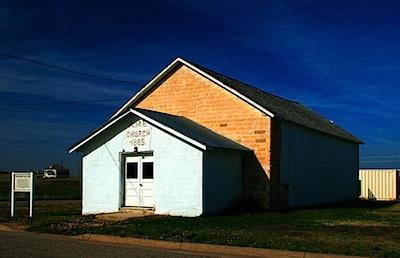

The rented Township Hall is one of five buildings that make up the site. The NPS owns the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, while the New First Baptist Church still owns the Old First Baptist Church. The American Legion owns the District No. l School, and a private individual owns the historic St. Francis Hotel. None are open to the public, though there are plans to open the foyer of the AME Church to visitors. Some of the buildings look ready to fall down, and one wall of the Baptist Church is being propped up to prevent that outcome.

The NPS has a brochure to help visitors take a walking tour of the site, and there’s an interpretive sign in front of each building. The park’s planning documents admit that none of these signs meet NPS standards, and some of them have minor inaccuracies. Though it’s beyond NPS control, the many vacant lots and the lack of any residents convey the sense that the town is dead.

The dilapidated buildings, outdated signs, vacant lots, and absence of people all tell the visitor that no one cares about this place. That’s not the story the park is trying to tell. The park wants to tell a story of courageous people building a new community on the frontier, a living community of people with close ties to the place who return regularly for Homecoming. Unless a visitor comes for Homecoming, however, the message is more one of neglect. This site appears abandoned not only by residents but by the National Park Service, Congress, and the American people.

It will cost money to preserve this place and tell its stories the way they should be told. If the American people and its representatives in Congress don’t want to spend that money, it’s a mystery why they bothered to preserve the site in the first place.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thank you, Bob, for another very interesting post.

I was especially interested and somewhat disappointed (but not too surprised) when I read this because for a long time now, I've been planning to visit Nicodemus on my way home from the air show at Oshkosh this summer. Somehow, the story of Nicodemus -- and the fact that it seems to be completely unknown -- captured my curiosity. Their NPS website touches on some of the challenges you mention. But even on the website, the staff's dedication manages to come through. I recall reading somewhere about the appointment of a new superintendent last year.

I'd love to hear the political backstory on this site. Maybe I can learn some of that next August.

Nicodemus just got a new superintendent in 2012. It is so far out in the plains that my wife said I could not apply b/c of the kids (lack of opportunity).

Thanks, Lee and NPSurvivor. For what it's worth, the new superintendent arrived not too long before I finished this article. I can imagine your being concerned about isolation, you'd have to live outside Fort Hays (an hour away) to have decent opportunities.

The more I hear about this little place, the more fascinating it becomes. Here's a link that will take you directly to the site's Newspaper. Interesting reading! More and more, I'm looking forward to stopping there in August or September.

As for being out in the plains -- isn't it true that we make our own opportunities? Some of my best memories come from places that were far from anywhere. Often the best people you will ever find are found in those kinds of places. Reading the Nicodemus newsletter makes it seem that's also the case here. There's apparently a lot of community involvement and interest.

About the only drawback I can see to a place like this is the fact that there are no mountains around. Can't live without mountains!

Normally I would agree, but quality of schools, availability of digital resources, shopping, and other "creature comforts" are important to my wife and kids. Being that far from many of these opportunities would be difficult for our family. I wouldn't mind, myself, but with family, it's different...

Yes, that can be true . . . . Perhaps we were also just lucky. One of our very best assignments came when it was 101 miles to the nearest real grocery store and there was no TV available. On the other hand, our kids were not in school yet and, at the time, reservation schools were more than a bit questionable. But that was back in the days when BIA actually did stand for "Boss Indians Around." Nowadays, I'd much rather have my kids in a rural school than one in a city of any size.

All that aside, however, I hope your time with NPS will be at least as good as mine was and that you and yours will be blessed in anything you do and any place you go.