Our National Park System now includes over 400 units, and none of them would be in existence today without the energetic efforts of individuals or organizations to secure the necessary authorization and funding. Such efforts are known as "lobbying," and the story behind Mount Rushmore National Memorial includes both a very creative approach for gaining a President's support...and a good example of what not to do in the halls of Washington.

In the early 1920s Doane Robinson was the South Dakota State Historian, and he is credited with conceiving the idea that massive stone carvings on a mountainside in the Black Hills would serve as a tourist draw for people from across the nation.

Robinson is known today as the "Father of Mount Rushmore," and according to park publications, he enlisted the support of several important allies, including Congressman William Williamson and Senator Peter Norbeck.

The Goal: "A Heroic Sculpture of Unusual Character"

In August 1924 Doane Robinson invited a sculptor named Gutzon Borglum to come to South Dakota and talk about the opportunity to create a "heroic sculpture of unusual character" in the Black Hills. Borglum replied promptly by telegram that he was "very much interested in your proposal," and by the end of March 1925, both the United States Congress and the South Dakota Legislature had been persuaded to pass legislation giving permission for the project to occur.

Permission to proceed was important, but finding the money to pay for the work was another matter entirely. According to a park history, "Early in the project, money was hard to find, despite Borglum's promise that eastern businessmen would gladly make large donations. He also promised the citizens of South Dakota that they would not be responsible for paying for any of the mountain carving."

By most accounts, Gutzon Borglum was a talented sculptor, an optimist, and a sometimes controversial individual; as the above comments suggest, he was anything but reticent when it came to promoting his project. Confidence and enthusiasm, however, don't always translate into money in the bank, and Congressman William Williamson became "the driving force in getting money appropriated from Congress for the construction of the memorial."

Seize the Moment to Get the President's Attention

In 1927 Congressman Williamson convinced President Coolidge to visit the Black Hills for a summer vacation, and the presidential party was housed at the State Game Lodge in Custer State Park. It's not clear how much coordination had occurred between the congressman and the sculptor, but it's surely not a coincidence that at the time of the president's visit, Borglum was planning a formal dedication of the nearby site of the massive stone carvings.

President Calvin Coolidge delivers a speech on August 10, 1927, at the Mount Rushmore dedication ceremony. NPS photo

If your goal is to secure White House support for a project, one good approach would be to convince the president to give a speech at a dedication ceremony. Even in 1927, however, capturing the president's attention'and some of his time while on vacation'was likely a challenging task.

This would require some creative lobbying indeed, but sculptor Borglum was up to the task. His solution: Hire an airplane'still something of a novelty at that time'fly over the Lodge where Coolidge was staying, and drop a wreath, inviting the President to the dedication ceremony.

The ploy was successful, and on August 10, 1927, President Calvin Coolidge not only gave a speech praising the project with suitably inspiring language, he voiced his support for federal funds for the project. On the basis of this achievement, I'll nominate Mr. Borglum's aerial delivery of that wreath as one of the most creative examples of lobbying for what eventually became an NPS area.

On the Heel's of a Lobbying Victory, a Bobble

Alas, on the heels of this win, the sculptor fumbled the ball, not once, but twice... and thus makes the list of examples of how not to lobby for a park'or any other government project. A document on the park website sums up the tale.

With the President's backing for the project on the record, "Borglum arranged a meeting with the United States Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon to secure his support for the project and the passage of a funding bill, the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Act. Borglum was able to convince Secretary Mellon of the importance of the project and gain his support for funding the entire cost."

Victory! Then, inexplicably, "Gutzon Borglum instead asked only for half of what he needed, believing he would be able to match federal funding dollar-for-dollar with private donations. Senator Norbeck was stunned that Borglum had turned down the offer of full federal funding."

Be Careful What You Ask For

As proof that you should be careful what you ask for, especially when politicians are involved, "President Coolidge signed the bill authorizing government matching funds up to $250,000. The bill also called for the creation of a 12-member Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission, with members appointed by the President."

Alas, a changing of the guard was approaching at the White House, so Coolidge chose to appoint only ten of the required twelve members of the Commission, leaving the final two spots to be filled by the incoming president, Herbert Hoover.

"When Herbert Hoover took office, he quickly appointed the final two members to the commission, but did not seem in a hurry to meet with the commission, as required by the funding bill before work on the memorial could begin. Congressman Williamson was asked to make an appointment with the President and request that he organize the first commission meeting."

Haste Nearly Spoils the Deal

The wheels of progress can indeed turn slowly in Washington, and a President's calendar is always full, especially early in a new administration, but Mr. Borglum was a man on a mission. He had a mountain to carve.

That zeal unfortunately led to lobbying bobble number 2.

"Frustrated by the slow pace, Borglum decided to attempt to visit President Hoover himself. When he arrived at the White House, Borglum got into an altercation with the President's secretary, and Congressman Williamson's appointment to speak to the President about the Commission meeting was cancelled."

The nature of this "altercation" isn't clear, but a key lesson in Lobbying 101 is "Don't upset the President's staff!"

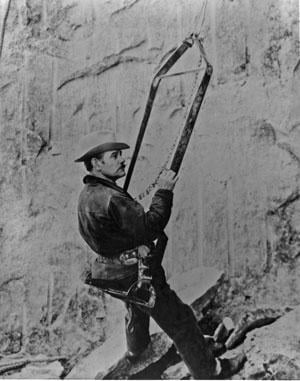

Gutzon Borglum is shown here in a Bosun's chair inspecting the work on the memorial. NPS photo

Congressman Williamson was eventually able to reschedule a meeting with President Hoover, right the ship, and receive approval for both the work and the first installment of funds.

Success At Last

John Boland, the newly elected secretary of the executive committee of the Mount Rushmore Commission, and Congressman Williamson went to see Secretary of the Treasury Mellon and pick up the first payment for the project. It totaled $54,670.56. There was no mention in this account that Gutzon Borglum was present to savor the moment.

The rest, of course, is history. Borglum remained actively involved with the project until his death on March 6, 1941, with his son Lincoln assuming a key role for the final two years of the on-site work. Gutzon Borglum died on March 6, 1941, as a final dedication for the carving was being planned. Mount Rushmore National Memorial was declared a completed project on October 31, 1941.

Along the way, lobbying in a variety of forms both helped and hindered the process, but when Gutzon Borglum was involved, the process was sometimes very creative...and rarely dull. The park website offers a nice summary of the nuances involved:

"Gaining permission to carve a mountain, acquiring funding and managing varied personalities were all a part of the challenge in creating Mount Rushmore National Memorial. For those involved, keeping the project moving forward often seemed more difficult than the actual work of carving the granite into a colossal sculpture of the four presidents. In the end, cooler heads, charm and determination allowed the memorial to become a reality."

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment