El Morro's great bluff towers over the landscape/Lee Dalton

El Morro ' the headland ' is nestled along an ancient highway in central New Mexico between the town of Grants and the Pueblo of Zuni. Once upon a time, a pool of dependable water at the foot of a great cliff dictated that travelers stop here. It was the only sure water for about 40 miles in any direction. Once it sustained a fairly large ancestral pueblo village atop the bluff before it successively quenched the thirst of Spanish Conquistadores, missionary explorers, and others of the Spanish colony known as Nuevo Mexico. Two hundred years later, they were followed by Anglo-Americans as they pushed a new nation's borders farther and farther west. There was even a caravan of camels passing when the U. S. Army experimented with using them instead of horses or mules in the Southwest's deserts.

The smooth, tan sandstone of the tall bluff seemed to be an attractive canvas for travelers and those who lived here. Villagers from the now-ruined village we call Atsinna decorated it in places with petroglyphs. Perhaps inspired by their work, the man who was first Spanish governor of Nuevo Mexico ' Don Juan de Oñate ' paused here to write the first known modern inscription in 1605. 'Paso por aqui,' he wrote. 'Passed by here. . . '

Now a few thousand people a year follow Don Juan and the others whose names are recalled here as they visit America's second or third national monument. El Morro was set aside by Teddy Roosevelt the same day -- December 8, 1906 -- he proclaimed Montezuma Castle National Monument after signing the Antiquities Act in 1906. El Morro is one of the little gems in the crown jewels of our national parks, and even though it may not be as noticeable as its bigger cousins, it is precious just the same.

I served as supervisory ranger at El Morro from 1971 to 1974 and remember it as one of my favorite places. It hasn't changed much. Quiet. Peaceful. Gentle. A place to savor and enjoy at leisure. A place where time seems to have called a time out and people long gone still touch our lives as we, too, pass by here.

I pulled in late the afternoon of May 14 and managed to snag one of the last two campsites in the nine-site camp on a road named 'Dark Sky Drive.' It's six in the evening now a day later, the camp is filled, but the only sounds are of a gentle breeze through the piñons and junipers and the ticking of a little clock inside my trailer. Silence reigns. Last night a coyote sang me to sleep and this morning at six I was thankful for my furnace when I looked at the thermometer outside and saw it stuck at twenty-four. It may be the middle of May, but at 7,300 feet spring is still struggling to get here. Once the sun rose above the mesa to the east, it warmed things rapidly, and by eight it was short-sleeve time again.

One of El Morro's best features is that it's a Fee Free area. No admission fee and camping costs nothing.

Juan Gonsales' signature from 1629 is still easy to read/Lee Dalton

Most visitors pass by here quickly. A fast stop at the visitor center. Perhaps a look at their new award-winning film, 'Paso por Aqui.' Maybe they'll jaunt out to the Inscription Rock Trail. If they are really feeling ambitious and energetic they may take the entire two-mile walk past the inscriptions and then up and over the top of the 200-foot sandstone bluff. There they will take a look at a hidden box canyon that has always reminded me of a special secret garden. They'll walk past a few excavated rooms of Atsinna and then descend a set of stairs. Back in their cars, they will rush on and never know how much they missed because they didn't tarry awhile longer.

I had been here a couple of years ago for the first time in a long time. On that visit I found myself profoundly disturbed by an obvious miasma of gloom that seemed to pervade the place. Rangers sat idly behind the information desk, greeting visitors as if we were intrusions. When I asked if any guided walks or other programs were scheduled, the answer was that 'we don't have enough staff for that. Budget cuts, y'know.' Hmmmm. Five rangers and volunteers chatting behind the desk and not enough staff? Okay. Whatever. On top of the rock, I met a Navajo maintenance worker. As he passed I commented that it was good to see someone watching over El Morro. His reply was haunting ' 'Well, someone has to . . . ' Later, in the campground I spoke with a couple more maintenance folks and learned one of them was the nephew of a man who'd worked here with me. But little things they said made me realize that all was not well at El Morro.

I wondered if it was because the superintendent's office is now 40 miles away in Grants. Ol' Robert L. Morris would have skinned us all alive if he'd gotten a whiff of this kind of discord. I learned that many, if not most, of the staff live offsite somewhere. Does the Park Service lose something when the people responsible for protecting and sharing our parks live somewhere else? Later, I wrote a somewhat critical letter to the then superintendent. Never received a reply.

Other things had changed, too. An absolutely obscene sewage lagoon located just east of the employee housing area is now the most prominent feature of the landscape viewed from the top of the great rock. A mile of sewer pipe could have placed that thing down at the northeast corner of the monument near the highway where it would not have been such a horrible eyesore. Whoever designed and approved that abortion should be drawn and quartered.

As soon as I walked through the visitor center door this time, however, I knew in an instant that there have been at least some changes. I was greeted with enthusiasm by supervisory interpreter Rick Best and two volunteers ' Frankie Anderson and Margie, whose last name I didn't catch. Much better than my last visit.

El Morro's waters once sustained the residents of Atsinna/Lee Dalton

Aside from the lagoon reflecting sun for miles, not much had happened inside the monument. There have been big changes in the larger community around it. More houses. More development. Inevitable change. But there's a much more subtle and, I believe, even far more important change. Today while I watched the movie, a Navajo man brought a young girl through to look at the displays. They talked very quietly in both English and Navajo as, I supposed, he explained El Morro to his daughter. Later, two busloads of third-grade students from Zuni Pueblo arrived. Well-behaved kids with teachers who wore Zuni and not Anglo skin. Kids who were enthusiastic about learning ' a stark contrast to the silent, wary kids I remembered from school visits long ago when a native youngster could be punished for speaking his or her own language and none of the teachers could. Around me today I heard conversations in both Zuni and in English and I heard English being spoken without the accents and hesitation that once had been there.

I had to smile and I thought that maybe, just maybe, our nation might be growing up and beginning to realize the value of all our citizens. I found myself hoping that each of the kids who shared the VC with me will grow up to bright and happy and prosperous futures. It looks like they are off to good starts.

Then they headed out on the trail led by a ranger and couple of NPS volunteers and a Zuni wearing a maintenance uniform. Wow. A maintenance worker doing interpretation?

I met him later in the day and learned that he's actually a Historic Preservation Technician. The name tag on his shirt reads simply, C. Chimoni. He's working at El Morro to preserve the park's administration building. Built in the 1930s of native stone and mortar mixed on site, he's trying to repoint the rock where original mortar is crumbling. It is, after all, a historic structure now. He explained that he works throughout the Southwest on similar projects. He told of how he's been experimenting, trying to discover just the right mix and techniques for making up the lime-based mortar needed to restore old walls to as original condition as possible.

The visitor center movie tells some stories of the challenges involved in trying to keep Inscription Rock's inscriptions from fading away. It recounts some of the well-intended but misguided attempts of the past that wound up causing damage. Then I remember in my own time here and elsewhere when my colleagues and I chafed at new requirements that didn't seem to make sense. Things that required piles of paperwork. Environmental and historic assessments. Scientifically based plans in place of just trying to do the best we could with what knowledge and materials we had available.

Did we cause harm? I hope not.

Looking back, I'm happy to see the additional safeguards now in place. Safeguards that hopefully will prevent debacles like the recent flurry at Effigy Mounds National Monument or more sewage lagoons to destroy a beautiful scene. Decisions and actions based not on hope alone but on good science, good history, and good sense. And even with all that, how can we really be sure we are doing it right? Is that even possible? Will still-developing knowledge someday show that we were wrong ' again?

Even green water is slaking on hot days/Lee Dalton

= = = =

About a mile east of the monument entrance is a small café called Ancient Way. I'd heard rumors of how wonderful their pie is, so decided to go find out if they were true. THEY WERE! Unbelievably good. Crust unlike the crust on any other pie I've ever eaten. Thin and flaky like some sort of exotic French pastry, and the cherry filling was definitely not straight from a can.

A colony of starving artists and musicians have found refuge in the mountains and forests around El Morro. Across the road is a small community art shop where local artists exhibit and hope to make sales. As I ate my pie at the café, a lady played quiet music on a harp nearby.

Next time I visit this land I'll have to remember to wander over to the Ancient Way to find out if rumors about their other offerings are as true as the one about their pie. But come to think of it, I'll be here tomorrow evening . . . .

= = = =

Evening and the campground is full again. I accept an invitation to join a couple beside their campfire. Jack and Marie Thompson alternate between northern Utah's winter skiing and Maine's summers. This is their first venture into the land of Nuevo Mexico. We talk awhile about parks and politics and the anti-public lands ravings of some of Utah's lawmakers. They tell me of a recent trek by a herd of ATVs into Recapture Canyon, an area in southeastern Utah closed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to ATV use because of so much damage ' a trek led by a county commissioner to gain attention with an election looming.

Then I find myself becoming an interpreter again and tell them tales I remember of El Morro's history. Of Cabeza de Vaca and Estaban, and the Seven Cities of Cibola. Of Fray Marcos de Niza. Of Coronado and his trip to where Kansas City now stands. Of Don Juan de Oñate and J. H. Simpson. And, of course, of Edward Fitzgerald Beale and the camels.

The moon begins to rise one night past full. In a campsite nearby, a young couple from Canada gently strum guitars and sing quietly. It all seems to fit together perfectly and I find myself thinking that, yes, this is the way it should be.

If anyone wonders why we have parks, this is the answer.

= = = =

The next day dawned bright and beautiful, so I joined Jack and Marie for a walk past the inscriptions and over the top of the rock. One problem exists, though, for those of us who want to remember the place with some quality in our photos. The visitor center and trail don't open until nine o'clock. By then the light has already gone flat. Opening so late deprives serious photographers of that precious Golden Hour of morning light. Then, back at the visitor center, we met a long-term seasonal ranger named Jeremiah Maybee whose knowledge of the area helped answer a number of questions that had been haunting me because some of my 40-year-old memories are shadowy.

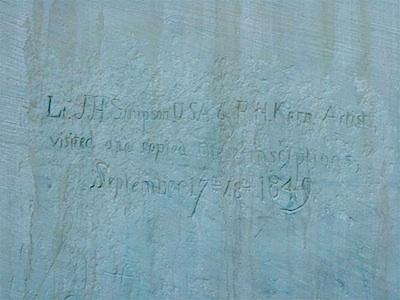

Lt. James Simpson and Robert H. Kern, an artist, passed this way in 1849/Lee Dalton

A bit later, however, came the only jarring note of this trip. I was trying to doublecheck the names of some of the people who had helped make my stay more pleasant so I could thank them here in Traveler. That's when one of the staff stepped in and told the person I was speaking with that if I planned to publish anything about El Morro, it could only come from someone in the superintendent's office. This person should not be talking with me. That ruffed my feathers in the wrong direction, but rather than make an issue of it, I apologized and ended the conversation.

I had already gathered that the past problems I'd seen at El Morro had been due to some serious internal conflicts. I'm sure that even though personnel have changed since then, there is still a need in the political structure of the local administration to try to avoid any potential embarrassment. What better way to do that than to try to control what may be written by limiting who may speak with a writer?

I'm sorry, but to my mind, that is not the way it should be. Yet given the realities of modern life in such a politically packed arena as our national parks, I guess I can understand it. It was things like this that led me to leave the Service many years ago. I'm sorry that it still exists.

I also noticed, but didn't ask about, an apparent absence of any interpretive programs at El Morro. The 'Programs' section of the campground bulletin board was empty, and I never saw any sign of any interpreters on the trails. Even if formal guided walks are not offered, the presence of an interpreter on a trail provides not only protection for resources, it also helps visitors make a human connection with what they are seeing. Even though I was greeted with a much different welcome at the desk, I still wonder what all those people in uniforms are doing if none of them are available to interact with visitors along the Inscription Trail. I'm an outsider now, but looking at things from an experienced point of view, it appears that what might be needed is a little creative leadership that remembers when you wear an arrowhead on your sleeve people are looking to you for an experience they won't soon forget. Those kinds of experiences don't happen at an information desk.

I'm sure that if I'd had the chance to ask more questions, I might have been provided with some reasons for what was happening. But everyone who works to manage our parks needs to remember that sometimes there is a fine line between reasons and poor excuses. Shouldn't the goal of any manager be to have a staff so well trained and feeling good enough about their jobs that one would not have to worry about what they might say ' even to someone who might write about it?

Mr. Long's carving is the most ornate at El Morro. He came by with Lt. Beale's Camel Corps/Lee Dalton

A few days later, I'd have an entirely different experience at Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

I also don't think I'll ever become accustomed to seeing law enforcement rangers armed to the teeth wandering through places like El Morro or Chaco or Hovenweep. I guess it may be necessary, but believe that if it is, then it's a tragic necessity. At least, though, on one night at El Morro I did spot a young law enforcement ranger with a dark mustache and beard walking from one campsite to another and actually answering questions of an interpretive nature. Unfortunately, I was visiting the little house on the hill when he stopped at my humble abode, so I didn't have a chance to talk to him. I'd have thanked him for getting out of his patrol truck and actually taking time to share with visitors stories of the place he protects.

To me, the don't talk incident only served to make my mission to spotlight and thank the peasants of the Service, the ones whose boots are on the ground and whose sweat falls on park trails instead of an air-conditioned office desk somewhere are all the more important. And I also know that I may be wrong or unfair in drawing some of the conclusions I've made here. Perhaps I'd have written something entirely different if I'd felt comfortable asking more questions.

I hope I won't cause problems for anyone if I thank the people wearing green and gray at El Morro ' even if I don't have official permission.

So thank you, Rick Best, C. Chimoni, Jeremiah Maybee, Frankie Anderson, Wendy Gordge, the mustachioed law enforcement ranger, and Margie Whose-Last-Name-Shall-Be-Unknown. Thank you, too, to all the rest of those I didn't meet who also labor at El Morro, whether they wear flat hats or hard hats. And thank you, also, to those who inhabit the Big Office in far away Grants.

Thank you all for working so hard to protect our special places. Thank you, too, for being courageous enough to be willing to stand up under the winds of political storms that may come your way. It ain't easy, that's for sure.

It's because of folks like all of you that I had the chance last night to sit in a peaceful campground and think to myself, 'This is the way it should be!'

Even if, sometimes, we could do even better.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Good lord, that sounds awful. I think it is a good example of how the dysfunction affects the public, and not just employees. I think the attitude of a lot of people in management is just "well, lots of people want to work for the NPS, if we have employees who are unhappy, we'll just get rid of them and find new ones." If it really didn't affect operations, they might have a point. This looks like a pretty over the top example, but visitor services are being damaged in less obvious ways every day.

The following was in the NPS Morning Report today. Given the earlier release by PEER of a report blasting management and maintenance of facilities at Pearl Harbor, this begs the question: What has happened to correct the apparent problems there? Does anyone have first-hand knowledge they could share?

World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument (HI,AK,CA)

Merry Petrossian Has Retired

Merry Petrossian, the park’s chief of facility management, retired on Friday, November 14th, marking a milestone in the NPS management of operations in Pearl Harbor.

Merry's presence at the site, working her way up the ladder from a part-time custodian (working several other jobs) to a division chief supervising some of her former co-workers, is a story of persistence and determination. She exhibited a strong ethic of caring for the site and its employees that helped raise the bar across all programs.

When asked about her most memorable part of working for the NPS, Merry referred to her receiving the NPS Director's Natural Resource Stewardship Award for Facilities Management. This award was an unexpected surprise to Merry, but recognized her efforts and response during an oil spill and subsequent cleanup. Merry was also responsible for the rip-rap along the shore of the visitor center. Her stories about being informed that she was nominated (on April Fool's Day) and her subsequent award presentation are priceless.

Merry's generosity and aloha spirit is well known in the park and in the broader NPS community. This generosity and aloha spirit will be remembered as an important aspect of what it means to be an NPS ranger in Pearl Harbor. Merry, in her manner, requested no grand recognition with her retirement and the park has respected her wishes.

“I ask that, in your own way, you wish Merry well in her new role as home-made honey supplier and full time grandmother,” said Paul DePrey, the park’s superintendent in a note to his staff. “The time gained by her children and grandchildren is a loss to the NPS, but one that has a higher purpose.”

[Submitted by Paul DePrey, Superintendent]