The serious birder of the 21st century is a bit of an amateur polymath. There's no doubt a thorough knowledge of bird identification is essential, but there's a host of ancillary disciplines that make for more rewarding and successful birding.

Some ornithology knowledge helps. This is the science of birds and bird behavior rather than just the birding hobby of finding and identifying them. Knowing what they eat, how they migrate, how long they live, what social structure they have, and how they keep from freezing in the winter are all worthwhile things to know.

A birder tends to learn geography whether he or she wants to or not. The where and when of finding birds is intricately tied into the lay of the land. An experienced birder can look at a satellite map of an area and make some pretty good guesses about where the hotspots before even hitting the ground with binoculars. Geography also comes into play when going after rare birds. If I'm in Big Bend National Park on vacation and hear that a very rare shorebird was just spotted at Padre Island National Seashore, can I make a quick day trip to see it? It turns out Texas is a rather large state! That one was obvious, but others don't come to mind as readily.

Botany is another science that gets thrust upon a birder sooner or later. It's usually when someone is trying to point out an exciting bird on a forest edge.

'See the tallest maple? It's at 3 o'clock in the patch of cottonwoods just to the right of that.'

Knowing your trees is also useful when it comes to finding birds on your own. Pileated Woodpeckers absolutely love Black Cherries. Yellow-throated Warblers are partial to Sycamore. Each subspecies of Red Crossbill specializes on different conifers. Knowing your trees will make you pay special attention when you find yourself in a habitat particular to a certain bird. It will also make you dislike invasive plant species all the more as they don't tend to attract nearly as much bird life.

The science that's been on my mind a lot for the past week is meteorology. The upper Midwest has had a problem for the last ten days or so ' north winds. The jet stream has had a dip that won't seem to budge (polar vortex, anyone?). Consequently, any birds headed north have been running into headwinds and heavy air masses that are stopping them cold around the Ohio River. The first significant wave of migrant warblers, thrushes, vireos and other songbirds typically arrives in the lower Great Lakes around April 25, but birders spent the last week of April in the traditional migrant traps looking at cardinals and chickadees in a stiff north breeze.

Rose-breasted grosbeaks were running behind on their migration this spring due to headwinds/Kirby Adams

We all turned to the weather forecasts to see when our beloved warblers would get here. The typical weather forecast doesn't tell you much. You need upper level wind predictions. You need to know whether you're looking at wind speed and direction at 20 meters or 200 meters. You need to know what direction air moves on the southwest side of a low-pressure system.

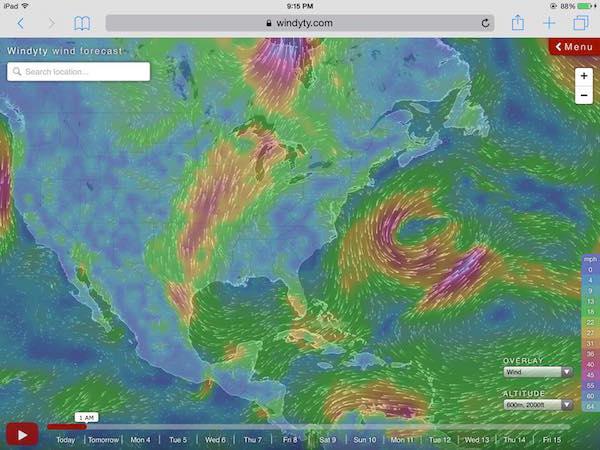

Actually, you don't technically need to know any of that as all of this was being discussed among birders on Facebook, but it's still fun to turn yourself into a amateur meteorologist. Sites like Weather Underground and NOAA provide most of the raw data you'll want. Windyty is an incredible site with real-time animated wind maps.

What we were looking for was the first evening when winds would be from the south. Most migrating songbirds fly in large masses through the night. They eat all day and take to the air for night migration, but only if the winds are right. They don't tend to fly into headwinds.

Initially it looked like things would be good in this region on Friday night, the first of May. As the day came closer, it looked like the wind wouldn't be favorable until too late at night, so Saturday morning wasn't going to be as good as expected. Sure enough, it was quiet on Saturday. Things appeared to be a little better for a Saturday night flight, but the experts predicted Monday would be the best morning.]

Right on cue, the reports of 15 species of warbler arrived Sunday morning, with even more on Monday. Now, here we are on Cinco de Mayo and we're finally seeing the birds we should have had almost two weeks ago. It may not seem like a long wait, but for birders starving for spring migration it's an eternity.

Thanks to some armchair education in meteorology and geography, we knew where to be and when to be there to greet our feathered travelers.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places