Editor's note: What role did the nation's rail industry play in the national park movement? Dr. Alfred Runte, in response to those who believe it was minimal, maintains the railroads not only helped substantially push the movement along, but opened the Western landscape to many who might not otherwise have seen it.

In responding to my article, Stephen Mather’s Ghost: Revisiting the Consensus for National Parks, five critics take exception that America’s railroads were instrumental in advancing the national park idea. Even if restored today, any railroad would pursue development. “Businesses exist to make a profit, controlled or not by the NPS. In our opinion, Dr. Runte could have emphasized ideas from other prominent national park scholars who have argued for parks being managed in more protective ways.”

Simply, they suggest, if the railroads were ever again to “win,’ it stands to reason the parks would “lose.” And so it was in the past. My perspective is too simplistic, they maintain.

This is to reemphasize how total has been America’s retreat from its railroads. Even educated Americans no longer see the distinctions between railroads and highway transport, especially how the automobile, not the railroad, became the principal destroyer of the national landscape.

As for the parks, I certainly take no credit for “discovering” how the railroads once embraced them. All of my material on Jay Cooke, for example, is the original research of Aubrey L. Haines. I quote from the dust jacket of his book:

Aubrey L. Haines was born in Portland, Oregon. After graduating from the University of Washington with a degree in forestry, he was employed as a park ranger in Yellowstone National Park. Following four years of service with the United States Army Corps of Engineers during World War II, he returned to Yellowstone and, in 1946, was appointed assistant park engineer. In 1959, he was promoted to the newly-created position of Park Historian, remaining in that post until he retired in 1969.

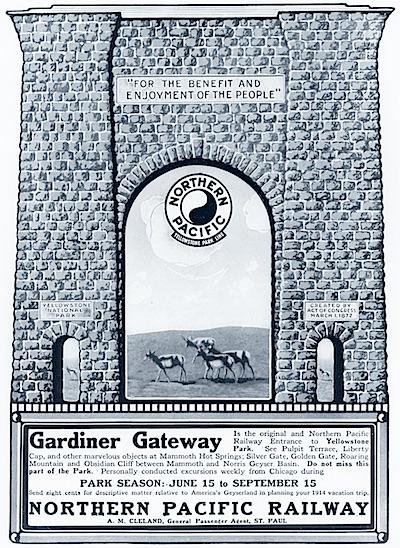

Railroad advertising constantly reaffirmed that the national parks were “for the people.” As of this reaffirmation, in 1914, a diverse tourist base still eludes the parks, but hardly a public understanding that the national parks were here to stay/Runte Collection

His two-volume history of the park, The Yellowstone Story, then appeared in 1977, itself published by the Yellowstone Library and Museum Association in cooperation with Colorado Associated University Press. In other words, the book was peer-reviewed. A preliminary volume, Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment, was published by the National Park Service and Government Printing Office in 1974.

There anyone may find Jay Cooke—exactly where I found him, along with his path-breaking influence on Yellowstone. Granted, he later went bankrupt. That still detracts nothing from his earlier contribution, which was no less than to orchestrate Ferdinand V. Hayden, Thomas Moran, Nathaniel Pitt Langford, and others, in calling on Congress for a Yellowstone “public park.”

Because that history came first, I naturally opened with it in my article, which PERC Reports asked that I limit to 2,300 words. If readers want more, there is a lot more. My book is called Trains of Discovery: Railroads and the Legacy of Our National Parks. Now in its fifth edition, it has been available since 1984. There is also my Allies of the Earth: Railroads and the Soul of Preservation, published in 2006. It, too, acknowledges my enduring debts to “other prominent national park scholars.”

For more on them, there is National Parks: The American Experience. Now in its fourth edition, it has been available since 1979, and was originally directed as a doctoral dissertation by Roderick Nash, still America’s leading scholar of wilderness and parks.

Simply, it does no good scolding the record. Those who need scolding are the ones ignoring history. Today, the National Park Service Centennial is mostly committees—most of them falling short. How do we know? Because they don’t even heed the agency’s own historians, as if to reinvent history has no consequence.

Last March, for example, there was that business about the University of California “founding” the National Park Service “idea.” The assertion was meant to promote a Berkeley conference about science in the national parks. UC Berkeley and the Park Service were among its co-sponsors.

What is wrong with a little spin? Everything. Misinformation feeds on itself, eventually to build mistrust. It is bad enough that Americans mistrust their government. History should not make the situation worse.

Ultimately, what apparently troubles my critics is that I failed to reinforce their spin. Yes, railroads developed the national parks, but then, the railroads were profit-motivated. As one consequence, only “the rich” could afford to travel while “the poor” were stuck at home.

Maybe, in the early days of parks and railroads travelers were similar enough to be counted as one type of tourist. But we know that other potential park visitors lacked income or social standing to use the railroads for travel to parks. If railroads had an understanding of how Americans understood parks, it could not have been a very diverse understanding.

The trap being set is a familiar one. These days, the moment anyone says diverse, the opposing side in a debate is supposed to buckle. “Maybe?” “Could not have been?” There is no research behind either claim.

Essentially, the rest of the rebuttal is just for show. The reader, too, is supposed to buckle before reaching Frederick Law Olmsted, Joseph Sax, and James Watt.

The ulterior motive is right up front. Because the railroads were profit-motivated, feel free to write them off.

Sorry, no buckling or write-offs allowed. I see the National Park Service Centennial in a different light. It is time to acknowledge everything that threatens wilderness, of which ignorance of the past is one.

For starters, other than by buying a first-class ticket, was there no other way for Americans a century ago to form an impression of their national parks? For example, did only the wealthy read newspapers and magazines? Did those lacking “income or social standing” simply cower in the shadows of national life?

Even if that were true (and it is not), every American city, town, and hamlet had a railroad depot and/or ticket office. Walking past the window, did average Americans—working Americans—not see a poster once in a while? Gee, I would like to go there. Perhaps some day I can afford the trip.

Lavish publicity was the railroads’ specialty—how, in the age before radio, television, movies, and the Internet, they kept the public informed. With specific reference to the national parks, some railroads, notably the Southern Pacific, owned entire magazines (Sunset). At 10 cents a copy and a dollar per year, Sunset was indeed meant to be accessible to the working public. After all, along with promoting the national parks, the Southern Pacific wanted more settlers to head West.

If price mattered, people could always read Sunset at the library or get one from a friend. I still read magazines at the barber shop.

In return, the railroads formed their “understanding” of the public through a myriad of responses, here, by the number of people asking for that poster or magazine. More broadly, the railroads tapped into the culture itself. What books were people reading? What kinds of pictures did they favor? At the state fair, and grandly that occasional world’s fair, what exhibits did they talk about the most?

Count on it. The railroads exhibited at those fairs, and yes, eagerly turned to exhibiting the national parks. Each exhibit would be staffed by ticket agents, passing out literature and gathering public comments.

These days, we wouldn’t even know how to mount a world’s fair. The first objection would be security; the second would be cost. Can’t we just put the exhibits on a smart phone? A century ago, the railroads were master exhibitors, and the public loved them for it.

Diversity

But okay, let’s play “Diversity.” Certainly, the game is all the rage. Granted, if in 1916 my forebears had wanted to visit the national parks as tourists, they simply could not have afforded it.

Besides, my father was indisposed. In 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm II had tapped him on the shoulder and sent him to the trenches on the Western Front. His two brothers were already there.

Our family casualty list? One dead (my Uncle August); one seriously wounded (father); and one so messed up inhaling cordite (Uncle Fritz) he would die of lung cancer at 49. Three years after his death, his son (my cousin Manfred) died at Bougainville in the Solomon Islands while fighting with the Americal Division in World War II.

For most people in the working class, the times were just not propitious for visiting the national parks. However, that is not to say working people were uninformed about the parks, or that America’s railroads, responding to the reality of pleasure travel, were the ones standing in the way.

Today, we should be so lucky as to have America’s original confidence that the country was on a noble path. Was America perfect? Has it ever been? No one argues that. But yes, drawing on America’s confidence—America’s idealism—railroads expecting to profit from the national parks noted meticulously how the parks contributed to national pride.

Simply, pride and profit were still interchangeable. Remember—we are talking about history—the difference between then and now.

The moment Jay Cooke “discovered” Yellowstone, every railroad wanted the same thing. If no railroad today seems to want that (and the few remaining apparently don’t), let us at least keep the history separate. Once upon a time the railroads believed in philanthropy, especially with respect to the national parks.

There, if I have made any contribution to original scholarship, it is to assemble and interpret, among thousands of images, publications, and artifacts, those that advanced the durability of the national park idea, regardless of the source. The point still remains: The railroads were the principal source.

Budweiser? Disney? REI? As shapers of a positive imagery, none has come even close.

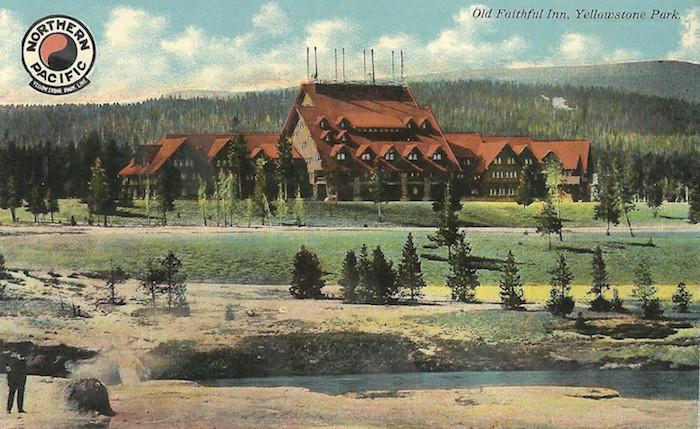

The Northern Pacific Railway loaned its hotel subsidiary $200,000 to build the Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park/Runte Collection

Today, business is all about “building market share.” The railroads were building the country. What does any builder say to a population of other builders? Here is how to build. “Make no small plans,” the architect Daniel Burnham advised, offering his design for Union Station (1908) in Washington, D.C. Robert Reamer, as the architect of Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone (1904), had already heeded that advice.

Great public spaces have always appealed to builders, and so the appeal of the national parks. They are “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” the railroads agreed. In the ultimate display of that conviction, all exhibited at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. UC Berkeley and Stephen T. Mather as co-founders of the National Park Service “idea?” An enticing bit of spin, but again, a wanting history.

Seven days a week, 24 hours a day, over a period of more than a century, railroads were the principal arteries of American life and commerce. Of course they were profit-motivated, but still as builders of the country, remains the point.

What is the distinction between a builder and a developer? Take a look. Your whole country has filled with developers. Have you seen anything like Old Faithful Inn lately? No, but you sure have seen a lot of new shopping centers, strip malls, billboards, and graffiti, and as a reminder for those living in Park City, Aspen, Jackson, Lake Tahoe, and Bend, thousands of so-called log cabins that are anything but.

The railroads were selling access, not sprawl. No doubt, the Western land grants were extremely generous. However, none was finally awarded until each increment of a railroad had been built. Consequently, the railroads eventually forfeited 50 million acres (out of 180 million) for noncompliance with the terms of their grants.

As for James J. Hill, he actually did have a land grant (the seventh largest), that from a preexisting railroad in Minnesota. Purchasing that, he then leveraged its land grant of 2.5 million acres to help facilitate construction of his allegedly “landless” Great Northern Railway.

Why the land grants and government loans? To speed construction—to build the country. Abraham Lincoln knew the importance of having the Union joined. On the West Coast, California and Oregon were already states. No less important, with the onset of the Civil War, Lincoln recognized the need for healing the country once peacetime had returned. Jobs and a bold project would help accomplish that.

In those days, the term “business basis” did not mean just profit and loss. It also meant ensuring that the country would last. Later applied to the national parks, it meant building those to last, as well.

Surely Dr. Runte, being an historian, knows that there never has been a clear idea about what parks should be–or are. Further, railroads have never been noted to have the pulse of all Americans when it comes to national parks.

Again, “never” is pretty big territory, and here it is being used twice. Is not permanence, “inalienable for all time,” a clear idea about what the parks should be—and are? Did Jay Cooke say anything about selling Yellowstone off to the highest bidder? No, he asked for “a public park forever” (italics mine). I will put that “forever” against my critics’ “never” any day of the week.

Yes, every railroad wanted to benefit from the leases—tourism—but it is precisely because railroads kept taking the pulse of America that the inalienability of the parks was assured.

Are the parks monuments; are they ecology; are they wilderness; are they playgrounds? Yes, those things we continue to argue, but not the permanence of the parks themselves. The business model of the railroads indeed was permanence, that in contrast to the automobile, which by unleashing a transportation free-for-all, gobbled up the parks from within.

Here is where those losing at Diversity, like Monopoly, always begin to cheat. You can’t put your token on that square! You can’t say America—you can’t say the people—until every possible victim has been identified.

If at any time—and in any place—some injustice still prevailed, you can’t talk about America the Beautiful. Lynching, strike-breaking, native dispossession—you name it—all prove that America was one big mess.

No, those things only prove that America still had grave injustices, as was true all the way back to Jamestown. When my cousin Manfred died in World War II, he was not fighting to spread those injustices. He was rather fighting to end injustice. There is the confidence America had—and no longer has—every time an injustice plays out in the news.

The democratizing influence of the railroad landscape remained a basic theme of railroad promotion, here a calendar painting by John Gould. Whether rich or poor, any child within waving distance of a railroad might know the American Dream/Runte Collection

Railroads emboldened America’s confidence and, by World War II, had secured middle-class status for millions. Meanwhile, they had not been sitting on their hands, waiting to be told what the public wanted. That is not how any business grows.

The general public was always in focus. Between 1885 and 1906, for example, anyone not privileged to visit Yellowstone in the flesh might visit for just six cents in postage. On receiving your six cents in postage stamps, Charles S. Fee, General Passenger Agent, Northern Pacific Railway, St. Paul, Minnesota, would affix them to a manila envelope containing a copy of Wonderland, the railroad’s 100-page, annual guidebook to Yellowstone and the Pacific Northwest.

Several days later, Wonderland would be in your mailbox. Did Charles S. Fee care whether you were rich or poor? Of course not. He only cared that you had shown an interest in Yellowstone National Park.

How did the railroads know that Americans wanted more parks? Because Fee alone needed 40,000 copies of Wonderland every year.

Posters from the railroads. Free. Brochures, postcards, calendars, and timetables. Free. Send in the coupon from our ad (and there were thousands of ads). We will send you a keepsake of the national parks you and your family can cherish forever.

Among the thousands still available on Ebay and at auction houses, you won’t get any for free. The point is: Thousands remain because the railroads distributed them by the millions, after which many were lovingly saved.

Think now of Budweiser’s image of the Statue of Liberty, offered for the Centennial next year. Will you lovingly save that beer can? Learn anything from it? The spirit of Charles S. Fee rests his case: A railroad image was about building dreams—and confidence. You mean to say we have such places in America? How wonderful! Perhaps someday I can see them, too.

Heading West

As for that someday, it came as early for many lacking income and social standing as it did for America’s rich. After all, someone had to build the railroads and staff the park hotels. Wanting to see the West, many found ways other than buying a ticket.

Millions went west, is the point, among them my maternal grandfather, who actually did it twice, originally arriving in New York City from Germany without a cent to his name. Earning his passage to America, he had hired out in the boiler room of his ship.

The year was 1891. Job by job, he worked his way to South Dakota. A skilled rider (trained in the German cavalry), his last job was caring for horses. As a final steppingstone to buying his own farm, he pinched every penny he made.

To his property he then added 40 acres still available under the Homestead Act. Remember that? Free land from the federal government. You bet millions headed west.

They didn’t sit around and whine, waiting for future apologists to call them disadvantaged. And while heading west—even on a third-class train—they saw all of America’s greater diversity.

The second time grandfather traveled west, he in fact took the train. It was 1910, and he was bringing home a second wife from Germany, his first wife having died in childbirth.

Six years later there would be a National Park Service. Seriously, does anyone mean to suggest that only “one type of tourist” knew about it—or the parks? An avid reader, grandfather knew all about the West. If the title said West, he devoured it. (He loved South Dakota.)

As for actually visiting the national parks, he simply didn’t have the time. In season (and farmers always had a season), he worked a 16-hour day, moving in 1914 to a diary farm just south of Binghamton, New York. (Grandmother had hated South Dakota).

His new schedule? Up at four to milk the cows and feed the horses. After breakfast, off to the fields until noon. No tractor. He walked behind the horses, guiding the plow with his arms.

After lunch, back to the fields with the horses. At five, time again to milk the cows. After dinner, the milk cans had to be set out for pickup (ever lift a milk can?) along with completing needed chores. If he was lucky, before turning in at eight, he got to enjoy one pipe and a few pages of Owen Wister, Mark Twain, or Zane Grey.

The national parks? They would have to wait.

His friends and neighbors were just as busy. It was still an agrarian age, after all. It would not tip urban until 1920, when finally half of America’s population lived in towns and cities of 2,500 plus.

That said, still an “understanding” of the national parks was close at hand—in still the flood of railroad lithographs, brochures, timetables, advertisements, calendars, posters, postcards, luggage stickers, ink blotters, traveling exhibits, and sponsored lectures. Even railroad freight cars were put to work, lettered to herald the “Yellowstone Park Line,” “Glacier Park Route,” or “Route of the Grand Canyon Limited.”

Maybe someday I can afford it. Maybe someday I will have the time.

Not enough diversity? Let’s continue our review. Looking out the window from his train, grandfather would have seen a plethora of diversity. After initially building the railroads beginning in the 19th century, thousands of workers were still needed to maintain and improve the rights-of-way.

Their ethnicity? The railroads hired every ethnicity, which again, brought a diverse population—not just wealthy travelers—right up to the doors of the national parks.

At Grand Canyon, the door opened just 100 yards from the rim. Does anyone really mean to suggest that working people were barred from those 100 yards?

To the contrary. Still as late as 1929, nearly 2 million Americans (out of 130 million total) worked for the railroads, further including telegraphers, dispatchers, station agents, freight agents, passenger agents, engineers, conductors, firemen, and many more. Even the smallest American town had a railroad depot. In major cities, stations still rose to palaces.

And yes, let us not forget the Railway Post Office. Remember the days before zip codes when Americans still knew geography—and how to spell?

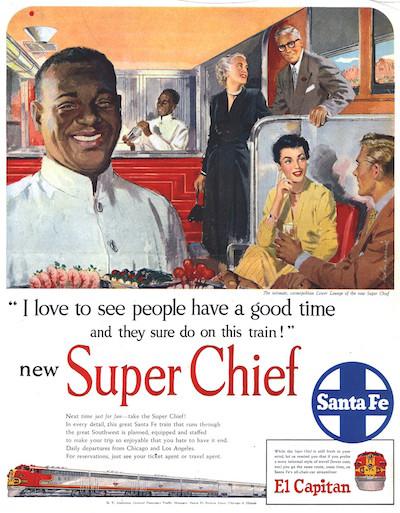

"The best job he ever had." A prestigious train, great tips, and solid membership in the middle class. Although not all American trains were as grand as the Super Chief, hundreds of others did come close/Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

The trains proper were staffed by African-American men. In the dining car they cooked and waited on tables; in the Pullman sleeping cars they made up the rooms. In the stations they were the majority of redcaps, hustling luggage to and fro. Most chair cars also had an attendant, as did parlor cars, lounge cars, and baggage cars.

Where trains were serviced or otherwise repositioned, car interiors were cleaned and scrubbed. Here, as distinct from when the trains were in motion, minority women often performed those tasks.

And let us not forget the Harvey Girls. Who were they? Among the first working women to see Grand Canyon while staffing El Tovar—and other famous railroad hotels—along the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe.

Did the Harvey Girls lack “social standing?” Well, because they waited tables and said “Yes, sir,” I suppose we could agree they lacked social standing. The point is that they did not lack initiative—or opportunity—if they really wished to see the West.

Many fulfilled that wish, further including the thousands of young people—principally college students—who worked the park concessions. Especially at Glacier, Yellowstone, and Grand Canyon, the vast majority arrived by train.

Yosemite’s “Curry Coolies,” as they called themselves, had to disembark at El Portal, while those working Zion, Bryce, and the North Rim of Grand Canyon rode the train to Cedar City, Utah. From there they were shuttled by bus. No matter, their fare was again either reduced or included with one’s contract.

Only someone intimidated by this history would reject it out of hand. Why the intimidation? For one, because we no longer “see” the history on the land. All we see now is sprawl.

For another, the Park Service grew up with the automobile; by 1930, the railroad era was winding down. As do we, the modern Park Service knows only asphalt. Relying on railroads again would mean giving up “control.” We don’t do railroads at the Denver Service Center.

Shuttle buses still need asphalt. Okay, we’ll let them in. Otherwise, we need an excuse to keep railroads out. At South Rim, the Grand Canyon Railway is called “entertainment.” People being “entertained,” the superintendent once told me, are less serious about the park.

Should that argument fail (and it has), there is always the argument here. Because the railroads were profit-motivated, they could never have been serious about preservation.

The automobile? The mobile home? The tour bus? The airplane? The helicopter? The Grand Canyon Skywalk? And those are the preservationists?

Truly, our postmodern look at history—as distinct from how those who made the history saw themselves—is beginning to sound pretty lame.

The Rest of the Story

Now you know the risk of playing Diversity—the risk of sounding lame. However, if we must continue playing, again, let us at least get the history right.

When the railroads declined, African-Americans were the biggest losers, having little where else to turn. Yes, America in the railroad age spawned a Jim Crow South, lingering racism in the North, and millions of members in the Ku Klux Klan. But that age also had the Pullman Company—and a hundred major railroads—turning America’s eyes to something positive. On the trains, greeting and serving the American traveler, a black man could stand tall.

On Diversity’s game board, that square is labeled “menial labor.” Oh, and everyone else had it easy? No one had it easy, is still the point. Miners, loggers, farmers, seamstresses, maids, cooks, railroad workers. It was a 16-hour day and six-day week for everyone.

At least the minorities working the trains could see something of America, perhaps even a national park. Although low-paid, the jobs were prestigious, including starched uniforms denoting class.

Improving their pay, African-Americans got tips, infamously 10 cents from John D. Rockefeller. In contrast, Bing Crosby is remembered for having tipped $900 when leasing out a private car served by four.

Railroad jobs, either in the depots or on the trains as porters and waiters, raised up pay levels and brought African-Americans across the country and into the parks. In this photograph from June 1940, the porter (white jacket, left) is serving the parlor car of the Santa Fe Railway's Grand Canyon Limited. Within a few hours, everyone (Pullman passengers, coach passengers, and workers) will arrive at South Rim/Runte Collection.

Yes, “the boss man”—the Pullman Company and the railroads—did everything possible to hold wages down. But that again meant everyone’s wages, not just those of African-Americans. Their tips the railroads could not control.

By itself, tipping—the generosity of travelers—propelled tens of thousands of African-American families into the middle class. When the railroads collapsed, those families were left with what? Well-meaning activists telling black men to “retrain”; social scientists demanding government welfare; but no practical way of recouping enough jobs to replace those lost.

More specifically, the kind of jobs lost. No need for college; no need for special skills, but yes, prestige and respect, and finally—for the first time in a century—the income needed to put your kids through college.

Few saw it because America was distracted, ultimately by the war in Vietnam. Nor were the airlines and Detroit shedding tears. But that is what happened to the black man, and why he still struggles to regain his feet. Gangs? Family abandonment? Drugs? All were worsened by the rapidity of losing so many jobs requiring little more than loyalty and commitment.

Just as the Civil Rights Movement reached its peak, the railroads reached their nadir. On the railroads, African-Americans—as the majority minority—suddenly found themselves out in the cold.

We should have saved our trains, good people, before singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Confirming the enormity of the transition, I took the time to ask, interviewing dozens of former railroad workers before they passed away.

A favorite source was Meredith, in the 1980s shining shoes at SeaTac Airport. He of course considered that a demotion, although it still paid tips. The job he longed for, and still called “his best job ever,” was the one he had ultimately lost. He had been a sleeping car attendant for the Pullman Company, starting in 1941.

How good was that job? Good enough to buy a house and put three children through college. “I did it all on my tips,” he confessed.

As railroads declined, so did their employment opportunities for African-Americans, along with their celebration of the American landscape. The airlines competed with sex and speed. Should this young woman get married, she will be fired. At 32, she will be "retired." What is she smiling about? Certainly not job security/Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

No less important was the pride. “Your neighbors saw that uniform and looked up to you. They knew you had money in your pocket.”

The airlines? He was blunt. “The airlines never wanted the black man. They just wanted pretty girls. I asked a couple times, but they said no.”

Say all you will that the railroads were not diverse. Like the national parks, it just isn’t true. There again, let us not forget the Buffalo Soldiers assigned to patrol the national parks. Granted again, they were not wealthy, nor visitors per se, but they were Americans forming an “understanding” of the inalienability of national parks.

If only the wealthy traveled—as in traveled first-class for pleasure—that was the times, not the railroads’ doing. And still the rest of it—98 percent of travel—was America on the move.

Trigger Warning

Today, our enemy is not the profit-motive; it is rather our failure to sustain that confidence. We instead get in everyone’s face. See here, Dr. Runte. I want you to tell us about the Chinese and how many died while building the Central Pacific Railroad across the Sierra Nevada.

Ignoring the exaggerated figure, any death is a tragedy, as it was a tragedy when Irish-American workers died while building the Union Pacific from the east. Civilization is never far away from tragedy, either natural or human made. The point is that by dwelling on tragedy you never get past it long enough to understand how far the nation has come—and why.

Challenging my students to see that, I would ask: Where else would you live? What other country would you fly to? While everyone seems to be flying here, why does no one seem to be flying “there?”

Although the railroads were never perfect, they further assured that immigrants kept coming here. Every time a railroad grew confident, so did society. If government alone is capable of advancing national confidence, it sure hasn’t proved it thus far.

Think of it this way. Absent our individual profit-motive (higher wages), and “their” profit motive (bigger dividends), how would government pay its bills? What would government tax?

As for the environment, there again, partisans find the truth hard to accept. The moment our culture abandoned the “old-fashioned” environmentalism of the railroads, we got interstate highways and sprawl. Not the railroads, but rather the automobile led to the homogenization of our country—and our parks.

Rather than acknowledge its own complicity, the Park Service itself seeks to rewrite the history. Just say diversity; just invent some “trigger warning” that keeps our role as developers off the radar.

Although unofficial, note the trigger warnings here. "Alfred Runte associates with PERC." The company he keeps is “bothersome” and “lurking.” “Whether the principles of PERC are those appropriate for national parks is debatable.”

Allow me a trigger warning. Stop hanging around the student center picking the debate you want and get your butts back in the library. There you will find many debates, the most informative not of anyone’s choosing. I didn’t choose to write this history; it is in fact the history.

As for PERC, they have never claimed to be infallible, but they happen to believe in libraries and history. They will listen to what anyone has to say.

Certainly, the three PERC conferences I have been privileged to attend would put most universities these days to shame, both for freedom of expression and intellectual rigor.

If that troubles anyone, look in the mirror. Accusing the messenger is weak. From where I sit, the onus is on the present to get its act together before rushing to condemn the past.

In the example here, the railroads did good things, and yes, some bad things. But that has always been the truth of institutions. Nation states also rise and fall.

Human perfection is forever elusive. All we can hope, for America at large, is that people resolve to repeat only the best things about their country, of which our national parks remain high on the list.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

I'll let the scholars debate this subject further, but wanted to add some additional documentation pertaining to this discussion.

In the Annual Report of the first (and only) Superintendent of National Parks, R.B. Marshall in 1916 acknowledged (pg. 3) that there were three classes of tourists to the national parks:

"The three general classes of tourists who visit our parks are: Those to whom the expense is of little moment; those who, in moderate financial circumstances, travel in comfort but dispense with luxuries; and, third,

those who, fired with the love of God's out-of-doors, save their pennies in anticipation of the day when they may feast their eyes upon the eternal expanse of snow-clad peaks and azure skies."

Marshall went on to insighfully say:

"Any plan, however, which may be devised for the management of our national parks should not be predicated upon the assumption that their function is solely to accommodate and retain our tourists in this country."

Stephen Mather, then Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, wrote in 1916 "Progress on the Development of the National Parks" (pg. 4):

"Informing the People. Realizing that success depends ultimately upon public support, and knowing that the people were surprisingly ignorant of the extent, variety, magnificence, and economic value of their national parks, I early inaugurated an earnest campaign of public education under the management of Robert Sterling Yard."

"To this end the information circulars were immediately rewritten, reorganized, and distributed under a new and effective plan. Last winter a descriptve booklet entitled 'Glimpses of our National Parks' was written by Mr. Yard to meet special educational needs. The astonishing demand that immediately developed for this book assured me that the public was eager for the facts."

"I followed this in the early summer by the publication, with the financial cooperation of 17 western railroads, of Mr. Yard's 'National Parks Portfolio,' an elaborately illustrated volume written and designed for the purposes of differentiating the principal national parks and presenting an adequate pictorial representation of each. An edition of about 275,000 of these was distributed over specially compiled lists and reached

appreciative hands. Forty-three thousand dollars were contributed by the railroads toward the cost of issuing these portfolios, and this sum represented only a small part of the contributing railroads' total expenses in advertising the national parks reached by their respective lines."

This was accompanied by a two-page map (pg. 20-21) showing the major rail lines west of Chicago. On pg. 9 Mather went on to say:

"National Parks to Pay Their Own Way. It has been your desire that ultimately the revenues of the several parks might be sufficient to cover the costs of their administration and protection and that Congress should only be requested to appropriate funds for their improvement. It appears that at least five parks now have a proven earning capacity sufficiently large to make their operation on this basis feasible and practicable. They are Yellowstone, Yosemite, Mount Rainier, Sequoia and General Grant."

Mather went on to say (pg. 27):

"Of first importance is the creation of the national park service, which makes all things possible."

"Of perhaps equal importance is the practical establishment on sound business lines of the princicple Government participation in concessioners' profits, which makes eventual financial indepedence for the national parks possible, and, wise administration, probable."

"Also of great importance is the creation of a spirit of hearty cooperation among concessioners, railroads, and park officials. There is much still lacking here, but the beginnings are inspiring."

The next year (1917), then Acting Director Horace Albright, in the first Director's Annual Report of the newly formed National Park Service, commented (pg. 17-18):

"Substantial Help of the Railroad...The three national park trip of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, including Rocky Mountain, Yellowstone, and Glacier National Parks, and the 'two national parks in two weeks' trip (Yellowstone and Rocky Mountain National Parks) of the Chicago & North Western and Union Pacific lines are instances of the efforts of the railroads to stimulate tourist travel to more than one park during the summer season. Practically no western railroad confined itself to promotion of travel to one particular park. The Northern Pacific Railway encouraged travel to Yellowstone and Mount Rainier National Parks. The Great Northern Railway promoted Glacier National Park and Lake Chelan in the Cascades. The Southern Pacific lines induced travel to Yosemite, Sequoia, Lassen Volcanic, and Crater Lake National Parks, and also to Roosevelt Dam via the Apache Trail, and to Lake Tahoe in connection with park trips. The Santa Fe promoted both the Yosemite National Park and the Grand Canyon Monument. The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad extensively advertised the Mesa Verde National Park, the Colorado and Wheeler National Monuments, and offered various side trips to Taos and the Cliff Dwellings of the Pajario Plateau. The Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul system encouraged travel to both Yellowstone and Mount Rainier National Parks. The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific lines devoted attention to the inducement of travel to several

of our national playgrounds. The same may be said of the activities of the Missouri Pacific system and the Iron Mountain lines. The Salt Lake route began the promotion of Zion Canyon (Mukuntuweap National Monument) and the other monuments in southern Utah. The Union Pacific system also aided in the development of travel to Mount Rainier Park and Zion Canyon in addition to the attention that it gave the Yellowstone and Rocky Mountain regions."

"The tourist bureaus and commercial organizations of the West have joined the railroads in making the national park system the general inducement for western travel, establishing them as the 'permanent expositions' of the West, as they were designated in 1915 in a speech made by Director Mather in San Francisco."

"The work that the travel bureaus of the express companies have done in the way of encouraging American travel in the park system is also worthy of special mention. A very useful pocket guidebook of the national parks, which includes the authorized rates for the 1917 season, was issued early in the spring by the Wells Fargo Express Co. and very wide circulation was given to it."

Just thought I'd toss out some additional food for thought.

The following comment is from Dr. John Lemons, Emeritus Professor of Biology and Environmental Science, Department of Environmental Studies, University of New England.

In our article ‘The Importance of Railroads in the Evolution of National Parks’ myself and four colleagues rebutted issues raised in Alfred Runte’s initial article in National Parks Traveler (NPT), ‘Stephen Mather’s Ghost: Revisiting the Consensus for National Parks,’ which itself was first published by conservative land–use think tank PERC.

In his rebuttal to our paper in NPT, Dr. Runte goes to great length to argue in a second paper, ‘Railroads and the National Parks’, some of the initial critical points raised about his article.

The biggest problem in Dr. Runte’s rebuttal is that he introduces issues that we did not, and he fails to address some issues that we made. Basically, Dr. Runte turned what should have been an author’s traditional response to readers’ comments into a long article, beyond typical rebuttal length. Our rebuttal focused on only a few of Dr. Runte’s assertions that he attributed to us.

One, we did take issue with Dr. Runte’s statement that ‘It was under the railroads that Americans had formed a clear understanding of what parks should be.’ Our response was that ‘…railroads have never been noted to have the pulse of all Americans when it comes to national parks.’ The railroads’ views about national parks never have amounted to much in the record of historical works, archives from the National Park Service (NPS), Congressional legislative history, individual parks’ management policies, legislative archives, case law, or academic scholarship. There simply have been no definitive conclusions that indicate that executives of railroads knew what the national park idea meant or that their conclusion held sway with Congress or the NPS or the American public. No one knew a definitive conclusion of the meaning of national parks–it was a point of contention. And still is. With one exception, all courts or venues in which the meaning of NPS legislation was an issue, courts and others made decisions that the fiduciary NPS mandate was to be consistent with the Organic Act of 1916, as Amended. Through the years, there has been no deviation from this kind of decision.

Two, Dr. Runte again devotes a considerable number of words in defense of Jay Cooke. The point, or question, that we asked in our article was: Why Runte should make Jay Cooke an ‘emblematic’ person in fostering the national park idea? Remember, the context for the question lies within Runte’s assertion that parks should be managed on a ‘business basis’ similar to how railroads were managed. Hence, it is appropriate to raise questions about the use of Jay Cooke as an emblematic person for fostering the national park idea, especially because Cooke went bankrupt, his railroad went bankrupt, and because he was involved in dubious business dealings with Canadian Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald that contributed to Macdonald’s defeat for prime minister in the 1873 election. Again, our point is that if one is to use someone from the railroads as an example in guiding national park policies and management, Jay Cooke is probably not a good choice.

Third, Runte devotes a large amount of his rebuttal article to issues of diversity–issues that we never addressed to any great extent, other than to say most early park visitors using trains to national parks were upper middle or higher in economic class. Runte wants to attribute to the railroads high standards in promoting diversity (e.g., ‘blacks had jobs in railroad cars and, through the public’s tipping this propelled them into the middle class.’). Now is not the time to discuss Runte’s views on diversity, and it is not our role to enter the discussion since Runte’s discussion has nothing or little to do with anything we said. Other readers with a greater understanding of diversity issues might wish to reread Runte’s rebuttal and offer some comments.

Fourth, Runte dismisses in a sentence or two the philosophies about national park experiences described by such writers as Edward Abbey, Joseph Sax, and Jonathan Livingston. We assert that their philosophies are much more in line with a nonconsumptive, reflective, and contemplative relationship with national parks; there is nothing in Runte promotion of railroads that indicate expression of any of the values typified by Abbey, Sax, and Livingston.

Fifth and finally, in his articles Runte fails to deal with the role of private enterprise in lobbying Congress and trying to make national park policies more developmentally–oriented (e.g., the efforts by Music Corporation of America to expand development in Yosemite, the efforts by Delaware North Corporation & Resorts to copyright historical Yosemite names, etc.). Runte’s first article in NPT was first published by PERC. PERC, as we mentioned in our response to Runte’s first article is a conservative neoliberal organization dedicated to absence of federal land ownership and policies within states’ boundaries, the use of an unfettered free market enterprise system to reduce conflicts between states and the federal government, and entranpenural relationships that focus on rights of private property owners and those active in the free market. PERC does not want more land protected by the federal government and has argued that management of some federally protected lands be given to private land owners or businesses. Most people who publish with PERC do not do so in professional peer–reviewed journals.

First, am I reading this right? Dr. Lemons is asserting the following: "The railroads' views about national parks never have amounted to much in the record of historical works, archives from the National Park Service (NPS), Congressional legislative history, individual parks' management policies, legislative archives, case law, or academic scholarship. There simply have been no definitive conclusions that indicate that executives of railroads knew what the national park idea meant or that their conclusion held sway with Congress or the NPS or the American public."

With all due respect to Dr. Lemons, I find it hard to believe that any academic would ever make such a categorical statement, especially pertaining to sources outside his field. Any one of the categories listed above could represent a lifetime of research, especially the archives of the National Park Service, Record Group 79.

In short, where did Dr. Lemons get all of those lifetimes? How does he know what so many records hold?

No one could possibly know, is the point. His rebuttal remains pure assumption meant to convey a prejudice, in this case that no corporation could have defended wilderness--nor are conservatives interested in defending it now.

"Fifth and finally, in his articles Runte fails to deal with the role of private enterprise in lobbying Congress and trying to make national park policies more developmentally-oriented (e.g., the efforts by Music Corporation of America to expand development in Yosemite, the efforts by Delaware North Corporation & Resorts to copyright historical Yosemite names, etc.)."

Again, he obviously has not read my YOSEMITE: THE EMBATTLED WILDERNESS, which is all about that issue. Peer-reviewed and published by the University of Nebraska Press, it has been available in national libraries since 1990. I am also on record in The Traveler, AP News, and elsewhere that Delaware North is running a scam.

Which brings us back to our railroads. They were not running a scam. They hoped to profit outside the parks, not on the inside. They only built the hotels because no one else would. A 90-day season in the Rocky Mountains? No one made a profit from that. But extra tourists on existing trains? Read Louis W. Hill. He is in my article.

Or don't take my word for anything. Still the history is not going away. Further in the category of "academic scholarship" Dr. Lemons alleges has "never amounted to much," there is Richard J. Orsi, SUNSET LIMITED: THE SOUTHERN PACIFIC RAILROAD AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AMERICAN WEST 1850-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. The holder of a Ph.D. in history from the University of Wisconsin, Dr. Orsi is Professor Emeritus of History at California State University, Hayward, and the past editor of California History, the publication of the California Historical Society.

I warn everyone that at 615 pages, including notes, SUNSET LIMITED is a hefty read. After all, the Southern Pacific Railroad was instrumental in developing the entire West, including land settlement, water, and agriculture in addition to conservation. Behind 35 years of research and writing are no less than 20 major archives, including the un-catalogued corporate records of the railroad itself. I am told those records covered the floor and walls of an entire warehouse. At that point, Dr. Orsi was down on his hands and knees sifting through the records. To be sure, the railroad by then was in decline and not particularly interested in its history, either.

I will cut to the chase with just one sentence on page 376 of his book. "Over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Southern Pacific Company compiled a distinguished record of support for wilderness and scenic-land preservation in the American West." Did everyone get that--a distinguished record? He is not saying a perfect record, or an unblemished one, but yes, it was distinguished. Note just one entry from his index: "parks and wilderness projects: in Lake Tahoe area, 371-73, leadership in, 196, 357-58; railroad's leadership in, 373-75; redwoods, 196, 373-74, 577n82, Sequoia as, 349, 363-64, 370-71, 374, 576n67. See also recreation areas, wilderness and wilderness preservation; Yosemite National Park."

Dr. Orsi is not arguing--nor am I--that the railroads of the country were saints. But yes, they did believe in the conservation of parks and wilderness, and yes, took the pulse of the country while doing so. Note another index entry under Muir, John: "railroad's alliance with, 349, 356, 358, 360." The Southern Pacific Railroad allying with John Muir and the Sierra Club? Of course. After all, Muir and Edward Harriman--also with controlling interest in the Union Pacific--were fast friends. "Muir's relationship with Harriman especially demonstrates how far Muir had come since the 1870s toward making peace with the industrial and corporate world. . . . Muir soon came to admire the man and his works, to appreciate Harriman's devotion to conservation and preservation causes, and to hold him and his family in genuine affection." (p. 366)

When Muir wanted Yosemite Valley returned to federal control, Harriman made the call to Speaker of the House Joe Cannon. "John Muir certainly deserves credit for having inspired and orchestrated the movement to protect the Yosemite. . . . However, the consistent support of the Southern Pacific over four decades was also important, indeed critical." (p. 369)

If you don't like Jay Cooke (and perhaps now Edward Harriman), there is also Frederick Billings--and another "missing" academic to tell his story. That book would be Robin W. Winks, FREDERICK BILLINGS: A LIFE: The Story of One of the 19th Century's Great Railway Builders and Early American Conservationists (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991). The late Dr. Winks, professor of history at Yale University, left us with this account on page 285: "While [Yellowstone] national park may have had its origins around a campfire by the Madison River, where members of the Henry D. Washburn expedition talked into the night of September 19, 1870, it was Jay Cooke and the Northern Pacific Railroad in the person of A. B. Nettleton who most effectively urged Congress to create such a park, and it was Billings as president of the Northern Pacific Railroad who reminded his chief engineer and surveyors, as construction moved up the Yellowstone Valley, that they should try not to damage the values of the land through which they would carry the line, since the time might come when the Northern Pacific would make as much money taking visitors to see the wonders of the West as it would make from the mines hidden in the mountains."

Again, Dr. Winks is not arguing that Cooke did it all, but he was the one "who most effectively urged Congress to create such a park." As for the rest of it, "try not to damage the values of the land," where is the highway engineer heeding that advice today, whether inside or outside the parks?

That makes three of us, Runte, Orsi, and Winks, all saying the exact same thing. Does anyone think we have a conspiracy going, or is it just possible that railroad affection for the national parks really did exist? As for PERC, agreed, the story shouldn't change just because of the sponsor. Then prove to us where we changed it before rushing to say we were "bought."

These days, colleges and universities are corporations, too. It starts with the football and/or basketball coach who, among state universities, is the highest paid university official in 49 states out of 50. Our football coach gets $6.5 million and is expected to fill the stadium. "The market," as it were, demands it. NIKE expects something for its logo, too.

And let us not forget all of those university "management teams" now numbering in the thousands. In most major universities, people never in the classroom have grown to outnumber the teaching faculty by a factor of ten to one.

What are young people and their parents paying for with a lifetime of burdensome debt? Bean-counting bureaucrats earning double what a history or classics professor makes. PERC hires only scholars, and yes, invites its most outspoken critics to share the floor.

Well, no one ever said higher education was perfect. If only it were still an education. Peer-review indeed.

Response to Mr Runte Comments on John Lemons's Comments about Railroads and Parks

First, I am no longer interested in pursuing what seemingly is becoming a personal argument with Dr. Runte. But I will stand by my decision, especially after looking at many documents used in case law studies and other laws– the role of railroads was not as Dr. Runte describes. The role of national parks always has been reliance on USC 16 SEC 1–4 as ammended. Further, there is no indication that the county relied to any great extent on what the railroads said, unless said railroads were directly involved in a lawsuit with the National Park Service.

Mr. Runte talks at great length about the purpose of national parks, but he seldom if ever mentions 16 SEC 1–4 as Amended which always has been the defining legislation for national parks, railroads or not with standing.

Mr. Runter wonders where I get the time for reading all of the many resources. Well, I worked with the NPS in Yosemite for 15 years, and my 40 years being a full tenured professor gave me ample time to devote to writing and publishing about park national services. I was not, as Mr. Runte says, hanging around the student union and by implication not doing my work. Maybe he was if he had not had a full time job (did he?)–but I was not.

Sometimes I think Mr. Runte is confusing tourism with resouce protection and natural scenery protection.

Finito

John Lemons

Ah, now I see the problem. Dr. Lemons wants to start the history with the National Park Service. Well, so does the NPS, and hence my article. By the time the NPS came around, the national park idea was well advanced, both legally and culturally, although no historian would deny that the Organic Act was a critical moment.

But how did the nation get to that critical moment and the establishment of the NPS? The railroads; it was what they wanted, themselves further inspired by preservationists fearful of another Hetch Hetchy.

This is not a personal argument, Dr. Lemons. It is rather the pursuit of history. If I have any argument with you, it is your denial of my right to have a sponsor just because you don't approve. You were sponsored by the taxpayers, and yes, I fail to see how they're getting their money's worth as university after university in this country becomes just another football school.

PERC is not sponsoring football. They are rather sponsoring scholarship. It's a wonderful feeling after all these years to be surrounded by people who think. Do they think alike? Not on your life, but yes, they are trying to find solutions to the mess our government has made of the public lands, as well.

See you in the library, and while you're at it, send a nice check to Kurt. The taxpayers aren't sponsoring him, either.

The National Park Service, in partnership with Amtrak, has created the Trails & Rails program in which National Park Service Volunteers provide interpretive programs on select Amtak routes. Reconnecting the national parks to railroads is made possible through this program which reaches a diverse population of Amtrak passengers. The volunteer Trails & Rails guides provide infornation on the cultural and natural history along the route and on Amtrak corridor trains provide public transporation information on getting from Amtrak stations to national, state and local parks. The national parks and passenger trains are once again connected and one can #FindYourPark via Amtrak.

Why use unpaid volunteers? Why not hire professional park interpreters for the cooperative "Trials and Rails" prgram?

On the issue of the "National Park Idea", to what extent have railroads promoted parks, in which the primpary purpose of those parks is resource protection and nature appreciation, as opposed to simply being promoted as tourist destinations? I can agree that railroads were quite important in promoting parks as vacation destinations. I'm less certain of their role in promoting the "National Park Idea" in which resource conservation takes priority over industrial tourism and wreckreation.

Runte himself overlooks some national parks history!

Namely, he doesn't talk about Yosemite, not Yellowstone, really being the first national park, and it being created years before any railroad was near it.