Editor's note: Last week Kenyan officials burned more than 100 tons of ivory tusk and one ton of rhino horn in a statement that the country opposes the illegal trade of ivory. Mark Deeble, a wildlife filmmaker in Africa, long has followed the issue and wrote the following article in the days leading up to the burn. Wildlife poaching the world over is a serious problem that needs greater attention and rooting out. Here in the United States the poaching of bears for their gallbladders is one example of the problem. Unless otherwise noted, photos are by Mark Deeble.

The Ivory Burn is about to happen and for days the internet has been full of pictures of the pyres being built, conservationists having their pictures taken with tusks, and heart-felt video pleas.

Despite the piles of tusks rising above the plains in some grotesque parody of a rural village, I’ve found it hard to contemplate the significance of what they mean in terms of individual lives. There are so many that it is overwhelming.

We’ve tried. We worked out that the number of tusks in the pyres represents a procession of elephants over 30 miles long, and while it creates a powerful mental image, it gets us no closer to the individuals.

I was looking through images of the piles of tusks, posted by Salisha Chandra, cofounder of KUAPO (Kenyans United Against Poaching), when one close-up caught my eye. What first drew my attention, was a spiral bound notebook, placed incongruously amongst the tusks. It was the tusk beside it though, that made me suddenly still.

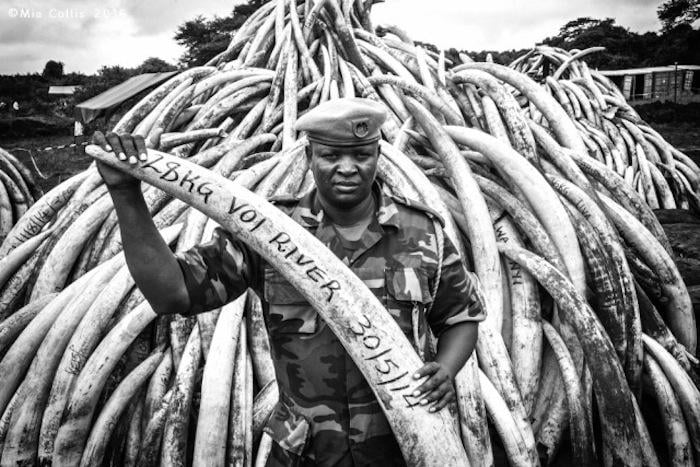

Like all the tusks there it carried information as to where and when it had been recovered – all I could see was .. .KG VOI RIVER 30/5/14, but it was enough. It was written in the perfect hand-written capitals that Kenya’s 8:4:4 education system produces.

The tusk is one in ten thousand, seemingly unremarkable – but the date and location made me remember.

At first I thought it fanciful. It seemed inconceivable that the tusk has come from an elephant we’ve known and written about. Perhaps I’d been looking for a connection to an individual to make sense of the masses, and willed it to happen. I closed my eyes, thinking that when I opened them, I’d see a different date, a different location – but nothing changed.

What were the chances that I’d see a random photograph posted on the internet that would contain a tusk that was known to me? What were the chances of that particular tusk ending up on the outside of a pyre, with it’s date and location visible?

To check my memory, I went back to photographs we’d taken of a bull elephant that had been shot by poachers, next to our camp in May 2014. The tusk’s date and location matched the camera’s metadata – there was no mistake. I shivered, my surroundings dropped away, and I was transported back to that dry river bed, where a dead bull lay, his tusks gone, his bones scattered by hyaenas – and hanging over it all, the clinging stench of death.

The bull had been one of an all-male herd that had taken over a nearby seep – I’d called them ‘The Waterboys’. Downstream from camp was a tiny seasonal oxbow lake beside the Voi river. When the river dried-up, the bulls dug down to the water-table there and patiently waited for a trunkful of water. It seeped through so slowly that they’d spend most of the day there – each waiting their turn in a hierarchy based on size, age and tusk length. On hot days, by the time the smaller bulls were allowed in, the bigger bulls would be thirsty again. They knew they’d only have a minute or two and in their desperation to drink, would collapse the sides and the whole operation would start over again. Like the teenagers they were, the young bulls took their frustration out by squabbling and jousting – which just served to make them hotter and thirstier.

As the dry season set in and the level dropped, the water was more difficult to reach and then the tables turned. The older bulls with the longest tusks were at a disadvantage then, as their tusks prevented them lowering their faces close enough to drink.

At the end of May, there was still plenty of water in the seep. Our bull would have drunk and then wandered upstream to feed – light crunched feet in the sand – it was only a few hundred metres to where Ndololo’s giant figs provided shade and food. The bend in the river-bed there was favoured by families that couldn’t get to drink at the seep. The matriarchs would dig down – penduluming a foreleg to uncover water hidden beneath the sand. Our bull probably joined them for a while – enjoying their company. The irony was that, in the heart of the park amongst other elephants and within earshot of people at the camp, he probably felt safe. How wrong he was.

What I remembered most from that time, was the overpowering feeling that his death was as bad as it gets – a brazen attack with an automatic weapon, next to a camp, just a few kilometres from park headquarters.

I’d written about his death in 2014 in ‘Another place, another Bull’ http://tinyurl.com/zs5frbl

The attack had happened just after dark, half a mile from our camp.

“That evening, just after sunset, there was a burst of gun fire a short distance upstream and a bull elephant collapsed and bled out in the riverbed. We didn’t hear about it until dawn the next day. The shots were heard from a tented camp, and by people camping close-by. They contacted Kenya Wildlife Service – their headquarters are only ten minutes away. They responded rapidly, but by the time rangers arrived, the poachers had hacked out one tusk and fled. The rangers removed the other. Later that night, hyenas chewed the ears, and the bull became immediately unrecognisable – faceless – just another statistic in a developing genocide.

I could imagine the scene – a mature bull elephant, digging for water in the moonlight – surrounded by females and calves. Within seconds, the tranquility shattered; within hours, the bull reduced to a one-line entry in a KWS manifest, a bloodied and numbered tusk in a strongroom, and another – probably already strapped on a motor-bike, en route to Mombasa.”

The poachers had escaped with one tusk, and shortly afterwards police in Mombasa seized two tons of Tsavo ivory from a warehouse owned by businessman, Feisal Mohammed. He’d immediately fled the country, but was later arrested in Tanzania and brought back to Mombasa, where he is still awaiting trial.

The other tusk was removed by KWS rangers. It was taken to Voi headquarters where it was cleaned, weighed and given a number that was entered in a ledger. It became part of the stockpile.

That was the last time it ever saw the sun – until a few days ago, when it was transported along with 10,000 others in eleven Maersk shipping containers to the burn site in Nairobi National Park. It would have been carried to a pyre on the shoulders of a workman, or perhaps ‘double-handed’ by a dignitary posing for the press. …KG/VOI RIVER 30/5/14 was a large tusk, and was given pride of place on the outside of the pyre. Standing upright, tip curving in towards the centre. That’s where it is now.

Two years ago I wrote, “We wouldn’t have forgotten him – but his identity would have slowly ebbed away. The next time the river comes down in flood, the bones will be rolled downstream, buried under sand – or slowly eroded to become sand themselves. In a year, there’ll be nothing left to show he ever existed.”

I’d forgotten about that remaining tusk – but in two days time, it won’t exist. It will be incinerated in a kerosene-fuelled conflagration, which, in the absence of sun under Nairobi’s rain-filled skies, will warm the faces of the invited dignitaries and Heads of State.

The international press that have descended on Nairobi will talk in terms of Kenya ‘setting an example to the continent’ and ‘closure’. Hopefully in years to come, April 30th will be seen as a day to remember all the elephants that the world has lost to poaching.

‘Lest we forget’ are three of the most powerful words in the English language, and we’d do well to apply them to elephants.

Lest we forget though, Feisal Mohammed is still awaiting trial. Despite the defence’s delaying tactics, the reassignment of the arresting officers, the missing files, the evidence that has conveniently disappeared, and the destruction of the crime scene by arson – there is still a chance that he will face trial and be prosecuted for his ‘alleged’ crimes.

For the Voi river bull that was killed in the moonlight by poachers on the 30th May 2014, that would finally be closure.

When the pyre is lit, I’ll think about that single tusk on the outside of the pile – a tusk that miraculously appeared again.

I’ll mourn a life that tangentially touched mine – and I’ll mourn the lives of the untold thousands that lie beside him.

Tusk Photo: Mia Collis

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Thank you for posting this great piece. Everyone needs to understand the severity of the poaching issue, and what we all stand to lose if it is not curbed.