Grand Canyon was a national monument before it became a national park/NPS

Editor's note: George Wuerthner, whose distinguished career has been built around exploring and explaining public lands, takes to history to defend the national monuments created by presidents who wielded the Antiquities Act.

Today's opponents of parks and monuments are on the wrong side of history

Last week, President Trump launched an unprecedented assault on America’s public lands when he ordered Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to evaluate whether dozens of national monuments should be rescinded or reduced in size.

Trump was responding to pressure from Utah’s congressional delegation, which has long hated the Teddy Roosevelt-era Antiquities Act, the law that gives the president the authority to safeguard lands and waters with outstanding physical or cultural attributes. Some — though by no means all — Utahns are upset about President Obama’s creation of the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, as well as President Clinton’s 1996 designation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

The long-running campaign against the Antiquities Act comes with a lot of red-hot rhetoric.

When Obama announced the establishment of Bears Ears, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch fumed, “For Utahns in general, and for those in San Juan County, this is an affront of epic proportions and an attack on an entire way of life.”

(Never mind that five Native American nations came together to support the monument, and that it enjoyed deep support nationwide.)

During the signing ceremony for his new executive order, Trump declared that he would end the “abusive practice” of establishing national monuments, which he characterized as a “massive federal land grab.”

(The president, clearly not much of a history student, is apparently unaware that since the Antiquities Act was enacted, every president except George H.W. Bush has used it. Trump is also evidently ignorant of the fact that the lands in question were already under federal control.)

Adding additional misinformation to the Trump pronouncements, Interior Secretary Zinke said that some national monuments are “off limits to public access for grazing, fishing, mining, multiple use, and even outdoor recreation.”

(Zinke, who at a White House press conference the evening before the order signing, boasted that “no one loves our public lands” more than he does, should know better. All national monuments allow public access, and nearly all of those in question permit outdoor recreation including fishing, camping, hiking, and even hunting in some designations. Livestock grazing is typically permitted where it previously existed. The activities most typically banned are logging, oil and gas drilling, mining, and sometimes closure of areas to off-road vehicles.)

If all the talk from Hatch, Trump, and Zinke sounds predictable, that’s because you’ve heard it before. The anger directed at national monuments is history repeating itself. Secretary Zinke’s statement that, “in some cases, the designation of the monuments may have resulted in loss of jobs, reduced wages, and reduced public access,” is an echo of arguments long made against parks and monuments. For more than a hundred years, there have been voices railing against “overreach” by distant authorities.

But the predicted calamities almost never materialize. And the same voices that once warned of economies destroyed by lands protection come to see that there’s more value in protecting a place than stripping it of minerals and trees. There have always been people who hate parks and monuments — until they come to love them.

According to retired University of Montana economist Thomas Power, many people, when thinking about lands conservation, suffer from a kind of “rear-view mirror” effect. We look at what industries drove our economies in the past, but are often unaware of what is currently driving our economies, much less what may be important in the future. “Not only are there economic opportunities that come with protected lands, including the obvious tourism-related business enterprises, but land protection has other, less-direct economic benefits,” Power has written. “Wilderness and park designation creates quality-of-life attributes that attracts residents whose incomes do not depend on local employment in activities extracting commercial materials from the natural landscape but choose to move to an area to enjoy its amenity values."

This rear-view mirror effect has always been one of the challenges of the conservation movement. Only in hindsight does the protection of a place seem obvious; in the moment, any decision to guard the earth from our immediate needs takes some measure of courage.

With the benefit of hindsight, then, it’s instructive to look at various park and monuments and recall how locals reacted to them when they were created, and how they view them now. A little history might give Trump, Zinke, and others some perspective — and maybe even cool their histrionics.

Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park/NPS

Then: Opposition to parks and other protected lands began with the very first federal land withdrawal. When Congress declared the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as the nation’s first national park, in 1872, the local reception to the news was negative. The editors of Montana’s Helena Gazette opined, “We regard the passage of the act [to protect the area] as a great blow struck at the prosperity of the towns of Bozeman and Virginia City.”

Now: Anyone who has visited Bozeman lately knows that it’s a prime location for new businesses and footloose entrepreneurs in the West due, in part, to its proximity to Yellowstone National Park. Indeed, a recent economic study by Headwaters Economics found that 2015 visitors to Yellowstone generated more than $110,000,000 in income to the Montana economy.

Grand Canyon National Monument/National Park

Then: In the 1880s, three bills to protect the canyon as a national park failed to gain traction in Congress due to local opposition. The Williams Sun newspaper in northern Arizona captured the common sentiment of the time when it editorialized that the national park idea represented a “fiendish and diabolical scheme,” and that whoever fathered such an idea must have been “suckled by a sow and raised by an idiot. … The fate of Arizona depends exclusively upon the development of her mineral resources.” In 1908, President Teddy Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act to establish Grand Canyon National Monument. Arizona’s congressional delegation was flummoxed by Roosevelt’s declaration and successfully prevented any federal funding for the park operations and tried, unsuccessfully, to legally challenge Roosevelt’s monument designation.

Now: Local attitudes about the value of Grand Canyon National Park had dramatically reversed by 1994, when the Republican Congress shut down the federal government, including the operations of national parks. Fearing a loss in tourism dollars, the state of Arizona offered to pay the costs of keeping the Grand Canyon National Park open to the public. In 2016, Rep. Raul Grijalva and conservation groups were urging President Obama to establish a Grand Canyon National Heritage Monument around the park. Some 80 percent Arizona residents supported the idea.

View from Hurricane Ridge in Olympic National Park/NPS

Mount Olympus National Monument/Olympic National Park

Then: There was significant local opposition when President Teddy Roosevelt created a national monument on Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula in 1909. Commercial logging interests were especially angry. M.J. Carrigan, Seattle’s tax collector, railed against the monument, which became a national park under Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “[We] would be fools to let a lot of foolish sentimentalists tie up the resources of the Olympic Peninsula in order to preserve its scenery.”

Now: The area’s U.S. representative, Congressman Derek Kilmer, has proposed legislation to add areas surrounding Olympic National Park. He’s a local and says he can’t imagine the area without the park. “As someone who grew up in Port Angeles, I’ve always said that we don’t have to choose between economic growth and environmental protection.”

Mount Moran reflected in Leigh Lake in Grand Teton National Park/George Wuerthner

Jackson Hole National Monument/Grand Teton National Park

Then: When FDR used the Antiquities Act to create Jackson Hole National Monument (precursor to Grand Teton National Park), locals went ballistic. Some feared that Jackson would become a “ghost town.” The Wyoming congressional delegation introduced legislation to eliminate the monument.

Now: Today, the “ghost town” of Jackson is home to 22,000 “ghosts” and Teton County is the wealthiest county in Wyoming, with an unemployment rate of 2.6 percent and a median household income of $75,325, compared to Wyoming’s median of $58,804.

Logan Pass, Glacier National Park/Kurt Repanshek

Then: When Glacier was first protected as a national park in 1910, the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce went on record opposing the park designation, fearing the park would preclude oil and gas and logging operations. Locals submitted a petition to the federal government in 1914 to dismantled the park, arguing “that it is more important to furnish homes to a land-hungry people than to lock the land up as a rich man’s playground which no one will use or ever use.”

Now: Today, the same Kalispell Chamber of Commerce brags about having the “best backyard in the country. A half hour to the east lies the rugged grandeur of Glacier National Park.” And contrary to the assertion that “no one will use or ever use” the park, according to the National Park Service, nearly 3 million people visited Glacier National Park in 2016.

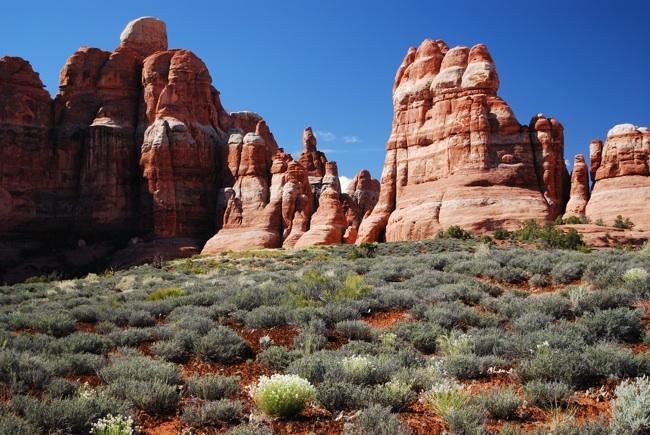

Chesler Park, Canyonlands National Park/Kurt Repanshek

Arches, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, and Zion National Monuments/National Parks and Canyonlands National Park

Then: Many of the national parks that anchor the economy of southern Utah — including Zion, Bryce Canyon, Arches, and Capitol Reef — were first protected in the 1920s and 1930s as national monuments. In the 1960s, efforts to make those places national parks, and to establish a Canyonlands National park, met stiff resistance from the oil and gas industry, ranchers, and Utah Sen. Wallace F. Bennett, who in 1962 predicted, “All commercial use and business activity would be forever banned and nearly all of southern Utah's growth would be forever stunted.”

Now: When congressional Republicans shut down the federal government in the fall of 2013, state officials in Utah rushed to keep the state's five national parks open. The move came with a hefty price tag — about $167,000 a day to run the parks. In 2014 speech on the Senate floor, Senator Hatch declared, “We owe a debt of gratitude to the people, both elected officials and citizens, who possessed the foresight to recognize the value of Canyonlands and created the park 50 years ago.”

George Wuerthner is the former ecological projects director for the Foundation for Deep Ecology and has published 38 books, many of them in conjunction with the late Doug Tompkins.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

APRIL/MAY 2017

A BEARS EARS ALTERNATIVE SOLUTION ...by Jim Stiles

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2017/04/03/a-bears-ears-alternative-...

Katahdin Woods and Waters. National Parks Conservation Association.

'Spiteful and Destructive': Maine Gov. Bans Road Signs to Obama-Designated Monument

Looks like you'll have to trust your map if you want to find the newly designated Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in Maine.

Gov. Paul LePage has refused to put up any official signs along the four main roads to the 87,500-acre preserve, which is on the list of 27 national monuments under Interior Sec. Ryan Zinke's review. President Barack Obama established Katahdin under the Antiquities Act last summer on forestland donated by Burt's Bees founder and philanthropist Roxanne Quimby

https://www.ecowatch.com/maine-ban-signs-obama-monument-2417881972.html

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/may/21/katahdin-woods-water...