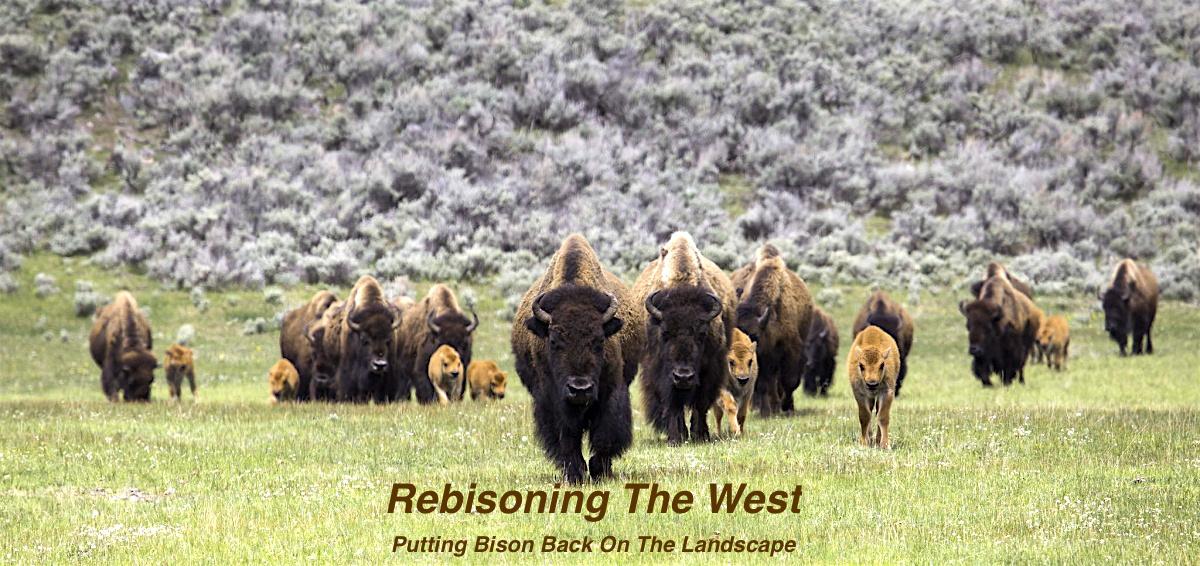

While Yellowstone National Park deals with brucellosis in its bison herds, efforts are underway via the Interior Department, National Park Service, Indian tribes, and non-governmental organizations to return bison to some of their historic landscapes in the West. In a collaborative effort, National Parks Traveler and WyoFile have produced a robust package of stories that examines efforts to repopulate areas of the American West with bison. These stories can be found at National Parks Traveler and WyoFile/NPS photo, Neal Herbert

♦

By Kurt Repanshek

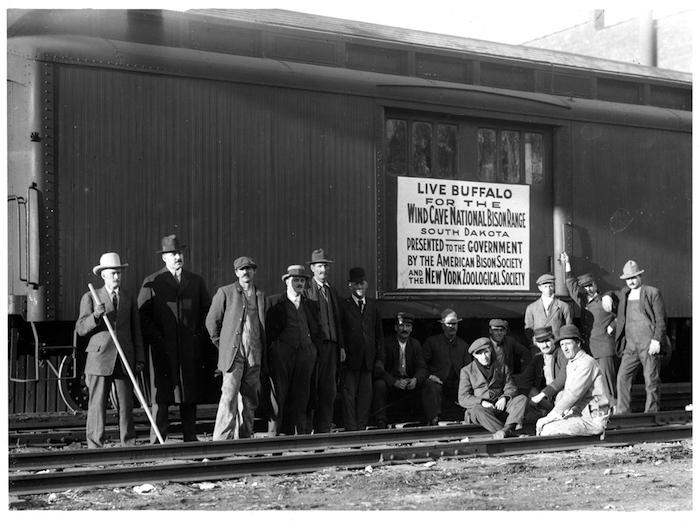

Clattering down the plank-lined chute, the 14 bison were leaving the big city for the high plains. Penned into individual crates that were then loaded into two steel express railroad cars, they rolled west late in 1913 on a 2,000-mile journey that would prove more astonishing than it might have seemed.

It was a cold, mostly cloudy day in New York City on November 25, 1913, when the bison left the New York Zoological Society grounds and began their trek to South Dakota, relying on the New York Central and Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad to get them to Hot Springs. The fee, by today’s standards, was inexpensive; just $850, and the cargo so highly valued that at one point another train was held “for two hours in order that these bison might make connections without delay.”

Three attendants rode in the cars with the bison and had timothy hay, oats, and water to provide the animals, most of which tolerated the train ride surprisingly well.

“All ate fairly well of hay and crushed oats after the first night,” wrote H.R. Mitchell, who documented the trek for the American Bison Society. “The greater number of the animals remained quiet and laid down and got up in their crates at their pleasure after they were once loaded in the cars, but several continued to be ‘scrappy’ all the way, and would kick the crates violently on the slightest provocation.”

Sixty-three hours after leaving New York City, and after passing through Chicago and then Missouri Valley, Iowa, the bison finally reached Hot Springs, South Dakota. There their crates were hauled out of those freight cars and placed on a variety of wagons for the final 11-mile jouncing haul to Wind Cave National Park. It was an auspicious start to what would prove to be a keystone for rebuilding the West’s bison herds.

Two steel railroad cars were used to ship 14 bison from the New York Zoological Society to Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota/American Bison Society

Bison, North America’s largest mammal, were designated the national mammal of the United States in May 2016. With bulls standing 6 feet tall and weighing as much as a ton, they long have been viewed as icons on the landscape. They appeared on the back of the Indian Head nickel that was minted from 1913-1938, as a symbol of the Interior Department since 1917, and part of the National Park Service “arrowhead” emblem since 1951.

Once moving across the Great Plains in herds that stretched to the horizon, the “great slaughter” of the late 19th century decimated the species and left only pockets of the animals on the landscape. Yellowstone National Park today is home to the largest free-roaming herds of bison, and the shaggy animals are revered by tourists who come to the park. Though many of the animals head to the park’s high country for the summer months, in winter they descend to the river valleys, where they use their massive heads as snowplows to uncover the remains of summer’s grasses and forbs.

While Yellowstone National Park is renowned for being home to the largest free-ranging herd of bison in North America, Wind Cave National Park is renowned for seeding bison herds in more than three-dozen locations, including an ecological reserve in Mexico.

Today there are ongoing discussions about where else in the West bison might be returned to establish herds. Never again will the Great Plains support tens of millions of bison as it did in the early 19th century. But there can be pocket herds of these incredible animals to protect their gene lines, restore ecological conditions to their natural state, and even just to delight visitors who want to view the United States’ national mammal.

Possibly central to those efforts will be the herd at Wind Cave because of its genetics. While late 19th century ranchers and some in the early 20th century worked to cross cattle with bison – even President Theodore Roosevelt considered it a great idea – a “large-scale genetics study, conducted from 1999-2002, found no cattle gene introgression in bison at Yellowstone or Wind Cave national parks,” the Interior Department noted in its 2008 Bison Conservation Initiative.

“I think the reason Wind Cave keeps coming up in bison (discussions) are the genetics of the park herd,” said Dan Roddy, a National Park Service biologist at Wind Cave. “The history of the herd goes all the way back to 1913, when we brought the first 14 bison in from the New York Zoological Park in New York City.

“Then, in 1914, we added six more from Yellowstone. It’s really all about your founder animals as to what we have now,” he continued. “Those original 20 animals, those are the only animals that have been brought into Wind Cave in the last 100+ years.”

Bison skulls from the "great slaughter" were ground up for fertilizer/Wikipedia

From Wind Cave, a park known primarily for its “hidden world beneath the prairie,” the pure genetic strain of Bison bison has flowed to 30 Native American Tribes, including the Yakama Nation in Washington state, the Iowa Tribe in Oklahoma, and the Round Valley Indian Reservation in California. Wind Cave bison also have been shipped to Antelope Island State Park in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, to Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas where The Nature Conservancy works with the National Park Service to manage the herd, and to TNC’s Rancho ‘El Uno’ in Mexico, an ecological preserve.

“Not only do we provide a lot of bison, there are a number of entities that now are looking for the Wind Cave bison because, what we’ve learned so far, is that there is no evidence of cattle gene introgression,” said Mr. Roddy. “So if you’re starting a new bison herd somewhere, like The Nature Conservancy, or a reservation, if you want to start with a genetically diverse group of animals, and ones that don’t have any evidence of cattle gene introgression, then where would you go?”

While Wind Cave and Yellowstone reportedly have the purest strains of bison genes, because of Yellowstone’s issue with brucellosis Wind Cave bison are sought out, he explained.

Rebounding Across The West

Today there are “conservation” bison herds, those kept to maintain sound genetics and a measure of “wildness” in our kingdom of public lands, in a small handful of national parks: Yellowstone, Wind Cave, Badlands, Grand Teton, and Theodore Roosevelt. Grand Canyon National Park also has bison on its North Rim, though it’s a controversial herd that goes back to efforts to cross bison and cattle. Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas also has bison, and in Alaska, at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, there’s a relatively small, 200-head herd of Plains bison transplanted there from the National Bison Range in Montana in 1928.

The number of herds could increase in the coming years, in part because of former Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, and in part because of the Blackfeet Nation in Montana. The Interior Department’s 2008 Bison Conservation Initiative “set the goal of restoring herds to their ecological and cultural role on appropriate landscapes within the species’ historical range.”

In 2011, when then-Park Service Director Jon Jarvis issued his “Call To Action” document that was to serve as a blueprint for leading the agency into its second century, one plank called for returning “the American bison, one of the nation’s iconic species, to our country’s landscape. To achieve this we will restore and sustain three wild bison populations across the central and western United States in collaboration with tribes, private landowners, and other public land management agencies.”

Secretary Salazar nudged that initiative further in 2012 when he issued a directive calling for short- and long-term proposals to transfer bison from Yellowstone to other federal or tribal lands “with a goal of restoring bison to their historic, ecological, and cultural places on appropriate landscapes.”

That May 2012 directive was followed two years later by an Interior Department report that further crystallized Secretary Salazar’s vision. It conducted an inventory of sorts where bison are found on the public domain, and lands where herds could be established.

The bison herd at Wind Cave National Park has been tapped from across the country to start, or supplement, bison herds/NPS

Today there are many landscapes, privately owned as well as in the public domain, with bison, from Ted Turner’s ranches that combined graze 51,000 bison to TNC operations at 13 locations that together manage about 6,000 bison.

Helping the Interior Department and Park Service spread bison into some of the species’ historic landscapes is the Wildlife Conservation Society, which traces its roots back to the American Bison Society that President Roosevelt and William Hornaday launched in 1905 to nudge bison back from the edge of extinction.

“As an organization, we’re really focused on restoring wild, free-ranging bison on an ecological scale, so we’re looking at places that are sort of matrix landscapes that are anchored by public lands but where there’s an awful lot of opportunity for restoring or repatriating bison,” said Kelly Stoner, WCS’s associate conservation scientist for its bison program.

While the Society is not involved with the Yellowstone bison issue, the organization is working with the Blackfeet Nation to expand its bison herds, and also acting as a facilitator of sorts to help the Park Service identify Western lands that possibly could support bison.

An intriguing aspect of WCS’s work with the Blackfeet Nation is the effort to bring bison from Elk Island National Park in Canada to the tribe’s reservation that borders the eastern side of Glacier National Park in Montana. Last year the first shipment, of 87 bison, arrived on the reservation, she said.

“The bison from Elk Island National Park are actually genetic descendants of the original bison herd that was found on the reservation in the late 1800s. Some hunters captured some bison calves, they ended up in the (1908) Pablo-Allard herd, and when that herd was split up these bison made their way into Canada, and now their (genes are) coming back to the reservation,” said Ms. Stoner.

The Blackfeet Nation wants to put bison back on the northwestern edge of its reservation, where Chief Mountain straddles the boundary of Glacier National Park/Rebecca Latson

Under the proposal being reviewed by the tribe’s business council, additional bison transfers would help build a herd on the northwestern edge of the reservation near Chief Mountain, a prominent, tribally significant, peak that straddles the Glacier-Blackfeet Nation border. In that case, some theoretically could roam into the national park.

“The idea is that could provide some economic opportunity and food security opportunity also in the form of hunting licenses,” said Ms. Stoner. “It’s a way of helping to push forward some of the related values that are associated with restoring bison. As a wildlife conservation organization, we’re really interested predominantly in restoring wild, free-ranging bison on an ecological scale.”

At Glacier, Superintendent Jeff Mow was watching the effort with great interest.

"What's exciting to me about the Innii Initiative is that it has high conservation values, high cultural values, and high community values for the Crown of the Continent,” he said.

On the federal landscape, one potential location for a bison herd is Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve in Colorado. The Park Service currently is preparing an environmental impact statement into the feasibility, and desirability, of placing bison in the park. Actually, some bison already roam part of Great Sand Dunes, as The Nature Conservancy owns the Medano-Zapata Ranch that adjoins the park, and some of its bison head into the park. Under the EIS, the park is considering the purchase of the ranch from TNC.

Badlands National Park, not far from Wind Cave in South Dakota, recently completed an environmental assessment into the possibility of opening more of the park to bison and is moving forward in that direction.

Then there’s the American Prairie Reserve, an ambitious project in central Montana managed by a nonprofit that envisions a 3.5-million-acre park that would range across a checkerboard mix of private, federal, and state lands. Once that park is completely in place, it’s anticipated that it will be able to accommodate 10,000 bison, said Damien Austin, reserve supervisor.

“We started out small in 2005, and then we’ve been boosting numbers. The Wind Cave (National Park) imports were like 15-20 animals, the Elk Island (National Park) imports, the first one was 93 animals,” he said. “Two subsequent ones were 75. So we’re trying to boost the population up over the 1,000-animal threshold for genetic preservation. Now the natural growth of the herd is taking over, and now we’re looking to expand the genetic diversity as much as we can.

“We’re working with a few different places to bring in some unique genetics. Possibly by next year we’re hoping to have some Yellowstone genetic animals mixed in the herd, and looking at some other source animals from the surviving herds that made it through the ‘big slaughter’” of the late 19th century, said Mr. Austin.

At the American Prairie Reserve in Montana, the goal is to have a herd of 10,000 bison/American Prairie Reserve, Gib Myers

Under the preserve’s management plan, small plots of private lands, strategically located next to public lands, are acquired to connect the lands. Then American Prairie works to obtain the grazing rights, either outright or through leases. Bison are then released on the landscape and so help “transition the land more into open ecology and natural grazing systems,” Mr. Austin explained.

“Currently, Sun Prairie is our main unit where we started, and that’s probably the most progressed piece of property. We’ve actually got a herd of about 450 bison on that properly, about 30,000 acres,” he said. “And they can move across from our private land to state land and the BLM. There’s no boundary, no fences, we just manage it cooperatively. That’s our ultimate goal, we blend the landscape together so we can move across from one side to another, the 3.5 million acres, and not encounter any fences or artificial boundaries.”

Conserving Bison Genes On A Large-Scale Landscape

From the Park Service’s viewpoint, the growth of bison herds in the West is key to conserving the species and strengthening its genetic pool.

If and when a decision is made to put bison at Great Sand Dunes, the agency “would probably want to look at the full portfolio of Interior Department bison, where we have 17 herds on U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NPS jurisdiction, two herds on BLM jurisdiction in Utah,” said Dr. Glenn Plumb, who retired September 15 as the Park Service’s chief wildlife biologist.

“We’d probably want to look at all those herds and say, ‘What would be the animals that we want to bring to Great Sand Dunes that would help that park meet its mission,’” he added, “'and contribute optimally to bison conservation?'”

But how far can bison expansion in the West go? The landscape is nowhere near as wide open as it was 150 years ago.

“Is there room in this century for large-scale wildlife conservation? Is the era of big conservation over?” Dr. Plumb asked. “Many people would say no. We’re still on the pathway, we’re still working towards the era of big conservation.”

But others, he added, would say that era has passed us by. Even when President Roosevelt and William Hornaday were working to prevent the extinction of bison, there were those who opposed their efforts, pointed out Dr. Plumb.

“Some of the things that people were saying in those first couple decades were that the time of buffalo had come and gone and it was foolish and it was aesthetic and it was self-serving, falderal, for people to be keeping bison alive and then bringing them back out to the West, and that there was no place for bison in the West.

“And these weren’t just spurious people in corners. These were organized voices, at state and industry levels. So, has that changed?” he continued. “A little bit. But there’s still a lot of uncertainty and a little confusion about whether or not in the 21st century bison conservation at large scale, with large numbers and with large assemblages, is a high priority.”

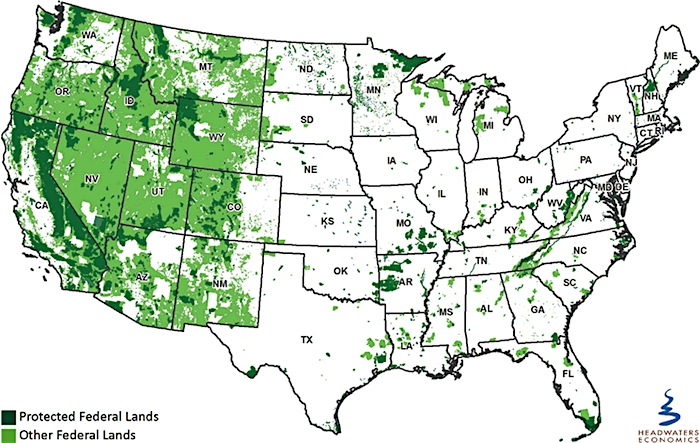

The vast array of protected lands and public lands across the West could make it possible to practice large-scale conservation/Headwaters Economics

At the Wildlife Conservation Society, which evolved from the vision embraced by William Hornaday and President Roosevelt, Ms. Stoner was of the opinion that large-scale conservation isn’t a thing of the past, but how it is implemented has changed.

“I do not think the days of large-scale conservation are over – rather, our definition of ‘large scale’ is evolving. For many reasons conservation has moved beyond relying on protected areas,” she said. “We have found that the established protected areas are not sufficient to support biodiversity at an ecologically meaningful scale. That is, we cannot cram all the biodiversity required to maintain ecological function into a protected area that is 1/10th the size of the ecosystem (or smaller).”

But, continued Ms. Stoner, when you look across the landscape, as the folks at American Prairie Reserve have done, you can find how different pieces of public and private lands, like a massive Jigsaw puzzle, can be pieced together to provide the habitat necessary for migratory wildlife, such as elk and bison.

“Our parks are sometimes protecting the ‘wrong’ areas if your goal is wildlife conservation. Protected areas are also static, but wildlife habitat use is dynamic. Migratory species are an excellent example of this –Yellowstone elk spend part of the year in the park, and part of the year outside the park. Expanding protected areas isn’t a feasible solution,” she said. “The human footprint is only going to grow, not shrink (which is what expanded protected areas would mean). And we would essentially have to protect everywhere in order to capture ecological function.

“So for all the above reasons, protected areas are not a silver bullet solution for wildlife. Parks, national forests, wildlife refuges, etc., certainly play an important role given that they hold land that is not as modified or impacted by human activity,” explained Ms. Stoner. “And when incorporated into a large-scale plan, they can form core areas for wildlife habitat protection. This is how WCS’s matrix landscape method came about. In the bison program, we talk about working in landscapes that are anchored by large tracts of protected land (usually national parks) and surrounded by an assortment of other types of land (forests and refuges but also agricultural land or state land). If we can get a partnership of organizations focused on a common goal for wildlife, then all these pieces constitute a large landscape over which wildlife can move.”

At Yellowstone, Superintendent Dan Wenk hopes the era of large-scale conservation is not in the past. And he just has to look at the lands surrounding his park to savor some optimism that it is not.

“Yellowstone enjoys the fact that it is the heart of an ecosystem that’s about 16-18-20 million acres, depending on who is counting the acres. And we are surrounded by five national forests, and that’s not usual for many parks in the West,” he said. “But certainly some of the major migration routes for any animal take them through private lands and so that makes it more difficult. I think the days of conservation are not behind, but I think the days of really great collaboration and cooperation with state agencies are becoming more and more necessary.

“Fortunately we do have a great conservation story with elk, and we have a great conservation story with grizzly bears,” said the superintendent. “I think we have the potential to work with those state agencies to have wildlife conservation that we can still look to for success.”

From Ms. Stoner’s viewpoint, finding ways to share the landscape with wildlife is key.

“I do think that if we cannot figure out how to coexist with wildlife then we have lost something as a society. The conservation scientist part of me could quote all sorts of research about nature deficit disorder and how spending time in nature and around wildlife is good for the soul,” she said. “But I also think that working together, across whatever aisles may exist in our society, is important. In that regard wildlife management can be a platform for building community and partnership.”

Comments

Thanks for this story, Kurt. I live not far from from Wind Cave National Park and have appreciated that the park's management has kept the genetics of their 1913 bision herd "pure". As stated in the story other herds now have domestic cattle in their ancestry, and this is a factor that should be monitored as herds increase around the country. By coincidence to your story, just north of Wind Cave Custer State Park is having their "buffalo roundup" this Friday (Sept. 29). It's not so much a roundup as a public tourism spectacle with some 10,000 people showing up to watch 1500 bison being driven across the prairie to corrals where they are sorted and checked for brucellosis, with some culled from the herd for later auction. Even though they appear the same, these bison are known to have cattle genes.