The Waterpocket Fold in Capitol Reef National Park/NPS, Jacob Frank

Editor's note: Frederick Swanson, a Salt Lake City-based writer, is working on a history of southern Utah’s national parks and monuments. He and his wife recently visited Capitol Reef National Park and returned home with this story.

If you pay a visit to any of Utah’s five national parks, much of the time your eyes will be riveted on arches, towers, cliffs and canyons. That’s only natural in places as scenic as these, but in the years that my wife and I have been exploring southern Utah’s park lands, we’ve found it worth our while to learn about their history as well. The signs of human occupancy in the national parks and monuments of the Colorado Plateau are often hidden, but they give important clues to how people have adapted—or failed to adapt—to the rigors of living in this harsh landscape.

In Zion and Bryce Canyon, Utah’s oldest national parks, most indications of historic human settlement and use, including early tourist camps and lodges, have been erased or relegated to museum displays. (The Zion cable works, which Lee Dalton featured in a recent article for NPT, is one exception.) In Capitol Reef National Park, however, the whole range of humankind’s encounter with the desert is prominently on display. Right next to the visitor center are the remnants of a successful Mormon farming village, carefully preserved as the Fruita Historical District. Old orchards and a few remaining buildings and barns survive in what must be the most picturesque setting anywhere. That humans have long been attracted to the mild climate and abundant water under the cliffs of the Waterpocket Fold is evident a couple of miles farther east on Utah Highway 24, where a fine panel of Fremont Culture petroglyphs is easily viewed from a convenient boardwalk.

Some of the orchards of Fruita/Bessann Swanson

Nine miles south of Fruita on the park’s scenic drive, a walk down Capitol Gorge reveals signs that this was once a main thoroughfare through the Waterpocket Fold. Pioneer glyphs and metal standards for an old telephone line adorn the canyon’s walls, but floods have erased all traces of the road. One can imagine how hazardous this confined canyon would have been to travelers in wagons or cars.

It wasn’t until 1962 that a modern road was finally blasted through the Fold. State road engineers debated whether to follow the original route down Capitol Gorge, but opted for the more direct route along the Fremont River. Driving east of Fruita on Highway 24, look for an abandoned river meander on the right where the road engineers completely rerouted the stream, creating a new waterfall on the other side of the highway. The falls used to be a great spot to cool off on a hot day, but unfortunately it’s now closed to bathers.

After Capitol Reef was established as a national monument in 1937, several motels were built on private land in Fruita, harbingers of what might have become a full-scale tourist village. It took decades for the Park Service to acquire these and other private inholdings within the monument, while at the same time trying to maintain the historic orchards and a few of the old buildings. The best preserved of these is the Gifford homestead next to the park campground. It’s now a modest living-history exhibit (my wife and I can vouch for the tasty pies you can buy here).

We’ve returned to Capitol Reef many times over the years, but we’d never visited the park’s southernmost extension, a long finger which reaches nearly to Lake Powell. This was part of the four-fold expansion of Capitol Reef National Monument that President Johnson signed in January 1969, just hours before he left office. That’s a story in itself, and is told in the unpublished administrative history of the park written by Bradford J. Frye (available online through the NPS’s Park History website).

Unlike at Fruita, the southernmost part of Capitol Reef (which was designated a national park in 1971) is not particularly known for its history. But as we explored further into this remote section, we came across scattered reminders of human use that date back many centuries. Scenery and adventure drew us to this out-of-the-way place, but as we witnessed more of its past, our appreciation of it grew. It’s a quest I’d recommend to anyone with some time to explore our Western parks.

Capitol Gorge in the 1930s/NPS

This part of Capitol Reef follows Halls Creek, a mostly dry wash that meanders southward for 40 miles, confined by the Waterpocket Fold on the west and a thousand-foot-high cliff to the east. Then it abruptly enters a narrow gorge carved into tilted-up beds of Navajo Sandstone. Now carrying a trickle of water, the stream loops and twists for a little more than three miles before emerging again into open daylight and continuing its way down to Lake Powell.

It was this narrows that led the two of us to load backpacks in our truck and make the long drive down the Boulder-Bullfrog road, also known as the Burr Trail. You can get to Halls Creek in fewer miles from Torrey or Fruita by following the mostly-dirt Notom Road south of Highway 24, but we chose the longer and arguably more scenic route over the shoulder of Boulder Mountain. Turning east at the picturesque hamlet of Boulder, we topped off our gas tank at Halls Store, an establishment so tiny that our purchase triggered an alert on our credit card.

Boulder has its own fascinating history as one of the last settlements in the 48 States to be accessed by an all-weather road, completed in 1940 over the slickrock leading from Escalante. In 1954 local historian Nethella Griffin observed that Boulder was “no longer the end of the road” as a crew funded by the Atomic Energy Commission worked to upgrade the Burr Trail, an historic cattle-drive route that snaked up scenic Long Canyon and over the Waterpocket Fold. This gigantic monocline forms the backbone of Capitol Reef and is stunningly displayed at the Strike Valley Overlook, located three miles north of the Burr Trail via a short drive or hike up Muley Twist Canyon. You need a high-clearance vehicle to reach the parking spot near the overlook, but we found it a pleasant one-hour walk--and there’s several surprise arches to see along the way.

After descending an improbable set of switchbacks farther along the Burr Trail, we turned south and drove for a dozen miles until the washboard gravel surface turned to pavement. A short distance farther came the side road to Halls Overlook—another high-clearance affair--which ends at a spectacular cliff overlooking Halls Creek right at the park boundary. There’s no camping allowed at the overlook, but we had obtained a backpacking permit at the visitor center in Fruita, so we parked the truck and signed in at the trailhead.

This stretch of Halls Creek is called Grand Gulch on topo maps, and for good reason: a great cliff stretches for miles to the north and south, forming a barrier that is passable in only a few places. The west side of the creek is bounded by the rounded, upturned slabs of the Waterpocket Fold, here clearly visible as an enormous flexure that draped successive layers of sandstone and other rock formations over a tectonic rupture deep beneath the Earth’s surface.

We were a little apprehensive about the thousand-foot drop into Halls Creek, but the Park Service has built a good, if steep, trail down the cliff, which we negotiated without difficulty. From here one can easily follow the wash bottom in dry weather, although hiker trails shortcut its wide meanders. The best trail can be hard to discern, so use a GPS app or consult a guidebook such as the one by Rick Stinchfield that covers all of Capitol Reef.

The walk down Halls Creek is usually advertised as a slog, but we found it to be anything but. Alternatively following the wash and sandy trails, we made good time to our first camp at Fountain Tanks, the first fairly reliable water in the canyon. Along the way we enjoyed the dark red outcrops of Entrada Sandstone that grace the east side of the wash. A few late-season asters and composites were still blooming—summer’s last hurrah. The biggest spectacle, though, came a mile-and-a-half after entering the canyon. Here the stream and trail skirt the Red Slide, the remains of a gigantic landslip that occurred thousands of years ago. It brought down a stupendous volume of rock and rubble from high up in the Circle Cliffs to the west, damming Halls Creek for a time. The remnants rises hundreds of feet above the streambed and are decorated with curious pillars of Moenkopi mudstone capped with boulders. An old bulldozer track leads up the slope to abandoned uranium workings high up in the Circle Cliffs—part of the boom in the early 1950s that sent prospectors scrambling all over southeastern Utah.

We were glad to have allotted two days for the nine-mile jaunt to the beginning of the narrows. Most hikers we met were doing it in less time, but we enjoyed poking up a few of the short side canyons which punctuate this stretch of the Fold. Prehistoric inhabitants must have found this area congenial for camps and hunting expeditions, although permanent settlements (as well as granaries and pueblos) appear to be absent. Every time we came across a pool of water in some side canyon, there were flakes of agate or jasper nearby. We speculated that hunters waited by these pools for rabbits or deer to come by. It was the full moon, and we could easily imagine a pair of young, sharp eyes watching for the motion of small mammals by its light.

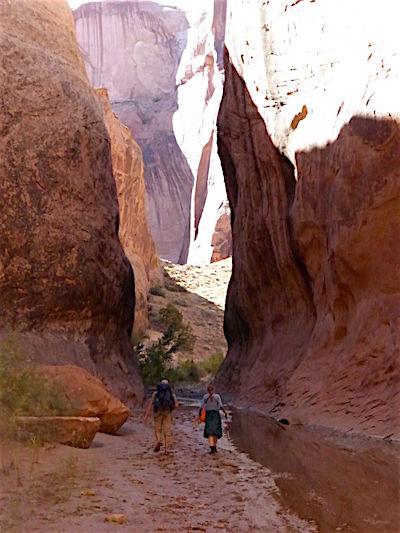

The highlight of our trek was the narrows of Halls Creek which, while relatively short, are certainly worth the trip. This isn’t a classic shoulder-wide slot which blots out the sky, although in places the enclosing walls form a “subway” not unlike the more famous one in Zion. At intervals the walls pull back to reveal enormous cliffs rising above. There’s a lot of shallow wading to be done, so river shoes are recommended, although we encountered only one deep (and mercifully short) pool which reached to our thighs. Conditions change frequently here, so inquire at the park visitor center when obtaining your mandatory permit.

Moenkopi Pillars/Jamal via Acrossutah.com

The scenery here is captivating, but there’s also a unique story to Halls Creek that dates to Mormon pioneer days. Most history aficionados are familiar with the Hole-In-The-Rock expedition of 1879-80, when a Mormon emigrant party traveled south from Escalante in search of a route across the Colorado River canyons enroute to Bluff on the San Juan River. A member of the expedition named Charles Hall went ahead to find a way through the cliff above the river, and once the party had caught up and maneuvered its wagons and gear down this steep fissure, he built a rude ferryboat to get everyone across. Hall apparently stayed behind with his family to run the ferry, but a year later he found a better prospect at the mouth of Halls Creek, many miles upstream where there were no tall cliffs. Hall and other pioneers fashioned a rough wagon road along the creek that now bears his name. For a few years it served the new ferry until a better route was established through Green River and Moab.

Little remains of Hall’s wagon road today; portions are visible where it crosses the Red Slide, as well as farther downstream where it provides hikers with a route around the narrows. Hiking down its length, we tried to imagine the imperative that drove these settlers to brave this inhospitable country. Whether it was religious idealism, a hope for a new life, or the quest for mineral wealth, something impelled people to trek down a windswept canyon for more than 50 miles, then cross a broad river on a makeshift ferryboat. And that still left dozens of miles of rough wagon road across the Clay Hills to Bluff.

The Halls Creek Narrows/Bessann Swanson

Farther upstream, Hall’s route crosses the Waterpocket Fold—a daunting obstacle if there ever was one. Nature provided the solution: a canyon deep enough to penetrate the Fold’s rock layers, yet wide enough to admit teams with wagons. It looped and meandered as water-gouged canyons will, leading to its name, Muley Twist. It’s a fine hike too, either as a day trip from the Burr Trail or as a two- or three-day backpack into its lower end.

As often as people have combed over the Waterpocket Fold for minerals or trailed cattle down its washes, this remains primitive country. Humans have yet to make their peace with the Colorado Plateau’s deserts, as we saw on our last night’s camp just outside the park boundary. We drove down a dirt road past a weather-beaten corral, next to which stood a derelict trailer. Its open door swung in the breeze as if it were in some western movie. Around it lay miles of deserted rangeland, if you could call these sparsely vegetated shale hills such.

Hunter-gatherers, cattlemen, uranium miners—all have come and gone in this unforgiving realm. As we sat in camp and listened to the wind stir the junipers and pinyon, we gave thanks for the silence, solitude and sheer beauty that we had enjoyed in this national park. These qualities of the landscape seemed to be the real treasure to be found along the Waterpocket Fold, and we hoped that they could be kept for a long time.

Frederick H. Swanson is the author of Where Road Will Never Reach: Wilderness and Its Visionaries In the Northern Rockies (University of Utah Press). He is at work on a history of the national parks and monuments of southern Utah. His website is www.fredswansonbooks

Comments

Thank you, Mr. Swanson, for this wonderful article. I felt like I was right there with you, exploring the route. Learning the history of a national park or monument always adds to an understanding of the place and people.

Thanks for an interesting and very informative article.

Let's also note that this portion of Capitol Reef was added to the park by Lyndon Johnson when he used the Antiquities Act in the closing days of his administration. Had it not been for the Act and Johnson's use of it, this wonderful part of a terrific park may have been lost.

Johnson's use of the Antiquities Act was certainly not without controversy at the time. And ever since then, the Park Service has repeatedly been forced to fight down attempts by locals and the Utah legislature to allow paving of the Burr Trail where it crosses the park.

Here's one more example of how much we all owe to the Antiquities Act. We have to ask what would happen if this addition to our parklands had been made today.

Lee, see graph 6.

The expansion of Capitol Reef certainly was controversial at the time (1971). Rumors were flying in southern Utah about President Johnson's action, including one that the monument would extend clear to Bicknell! And the town council of Boulder voted to rename their little village "Johnson's Folly." (It didn't stick.) But without the expansion, much of the Waterpocket Fold as well as the very scenic Cathedral Valley farther north would have been left open to mining, new roads, and other development. You're right that setting aside federal land has never been very popular in that part of Utah.

Graph 6???

Paragraph 6 mentions President Johnson's role.

Oh, PARAgraph 6. I was looking for something with numbers and squiggly lines . . . .

Yes, I read that and was just trying to add a little to it.

Capitol Reef N.P. is a true gem amongst all the western national parks. It doesn't have the same renown that the other nearby Utah parks enjoy even if the scenery is on par with those glitzy gems. It also doesn't share the same visitation pressures one encounters at Zion or Arches, either. I've enjoyed several visits to it over the year but I never knew that the Gifford House served pies. And right next to the campground where I was staying. Oh, the humanity! Looks like another reason to visit the park again.