Road overwash occurs in the Mineral King Basin of Sequoia National Park when culverts fail due to deferred maintenance/NPS

SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK _ Cars crawl up the steep, single-lane road, winding between eroded edges and over pavement cracks, with cliff drop-offs and stunning vistas emerging around bend after bend. Drivers need to focus, and that means resisting the scenic distractions of burbling streams below and Sequoia tree giants stretching above.

This is Mineral King Road, built to reach mining claims in the late 1800s, a 15.2-mile gateway to a Sierra Nevada valley so appealing that none other than Walt Disney once sought to put a massive ski resort here.

“Drive into the valley and it’s like going back in time to the turn of the last century,” said Woody Smeck, superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. No overstatement there: much of the road bed remains as constructed in 1870. Smeck added the obvious: “That’s a bumpy road that needs a lot of work. I worry about it because its narrow and winding from a traffic safety point of view.”

It’s not heavily trafficked like the extensive road networks of parks like Yellowstone or Natchez Trace Parkway. But just like those workhorse routes, Mineral King Road owns a piece of the $11.6 billion maintenance backlog in National Park Service locales across the country.

The transportation portion of that backlog is daunting, in need of nearly $6 billion to get a massive network -- 5,000 miles of paved roads, 6,000 paved parking areas and 1,400-plus bridges -- in proper condition. Shuttle systems and unpaved roads add to the ledger.

The backlog is a result of budgets that haven’t kept pace with the pressures of aging infrastructure and soaring park visitation, up from 256 million people across the parks in 1990, to 331 million last year.

From 2006 to 2013, parks spent about $461 million each year on transportation assets and services, according to the Interior Department’s 2017 Long Range Transportation Plan. From 2015 to 2020 the report forecast $394 million per year -- clearly short of the estimated $1.5 billion a year it says is needed to bring all transportation assets into good condition.

The backlog has grown beyond anything Congress should have allowed, says Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., who serves on the subcommittee on Public Lands and Environmental Regulations.

“There is a tendency, particularly by some in Congress, to pretend that our crumbling national parks are the result of bad luck or poor planning. This is an intentional mischaracterization by the real culprits in this tragedy,” he said in an email. “Congress after Congress has not been willing to spend the money we need to sustain world-class public lands.”

Glacier National Park's Many Glacier Bridge, damaged in June 2017 by a careless driver, remains in need of repairs. The bridge is used for pedestrian and horse traffic/NPS

The problem drew a glaring spotlight right under Congress’ nose in 2015: the historic Arlington Memorial Bridge, a front door to the nation’s Capital and busy commuter route carrying 68,000 vehicles a day, was revealed to be so shockingly corroded that highway officials warned it would have to close in 2021 if not fixed. Buses and heavy vehicles now are banned. Congress and the Interior Department have cobbled together $227 million for rehabilitation to start later this year.

The money is coming in part from postponing bridge work on the scenic Baltimore-Washington Parkway, a National Register of Historic Places route that the Trump administration now is working to transfer to the state of Maryland. “The Department of the Interior is not in the business of managing commuter highways,” Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke said in announcing the transfer project in June.

Uneven Upkeep

The National Park Service in fact cares for a large and historic network of roads, many well beyond their expected lifespans, degraded by weakened drainage systems, storms, heavy vehicles and traffic. Short on year-to-year funding, park officials say they have a hard time staying ahead of patching and small rehab projects. Left unaddressed, those grow into bigger, more costly problems – and grow the backlog.

“It’s some of the less critical prevention maintenance that we struggle with, like painting the steel girder of a bridge,” said Mike Molling, maintenance supervisor at Blue Ridge National Parkway. “It’s not imminent failure, but it’s critical for the overall life of the bridge. It’s critical work to do. You’re turning what could have been a cheaper preventative maintenance into a longer term rehabilitation.”

Yellowstone National Park, for example, recently announced that its 273-foot Lewis River Bridge, more than half a century old, has reached the point of requiring either "extensive rehabilitation" or complete replacement. The Park Service is proposing a $10 to $15 million project. Roughly half of the park's road system also is in need of repair, with work being addressed bit by bit.

The Lewis River Bridge in Yellowstone needs to be completely overhauled or replaced/NPS

Forty-two bridges on parks’ paved roads are officially rated as “structurally deficient,” although still safe to drive on; they would be closed if unsafe, officials say. Their age and continued decline, along with rising costs, “will make maintaining average good condition more difficult in the future,” the Long Range plan states.

“If they’re not maintained and modernized when they need to be, they’re so much more prone to being knocked out when challenge comes,” especially from increasingly harsh storms, said Kevin Cann, a former Yosemite maintenance chief and deputy superintendent, now a member of the Mariposa County Board of Supervisors in California.

Paved roads, visitors’ runways to the nation’s most treasured sites, and paved parking areas are rated in “fair” condition across the parks. Modernization of heavy-use roads like Blue Ridge Parkway and General’s Highway in Sequoia occurs a few miles at a time, while secondary roads often languish. The costs of getting to and working in remote, rugged terrain, as well as the need to protect natural, historic and cultural resources, make projects all the more expensive. Even temporary housing for road workers has to be factored in with hard-to-reach parks.

To substantially dent 469-mile, scenic Blue Ridge Parkway’s backlog over 10 to 15 years, Molling said, would require doubling the $7-$10 million a year he gets from federal highway funds for major repairs and rehabilitation. The Appalachian roadway, and its more than 150 bridges and 25 tunnels, suffer erosion from the sides and underneath as broken-down drainage structures fail to divert stormwater away. Blue Ridge needs $350 million worth of work, according to the Park Service.

“It’s a balance between having money for paving, repairing tunnels or repairing bridges. There may be a year where all I can do is paving and nothing on bridges or tunnels,” Molling said.

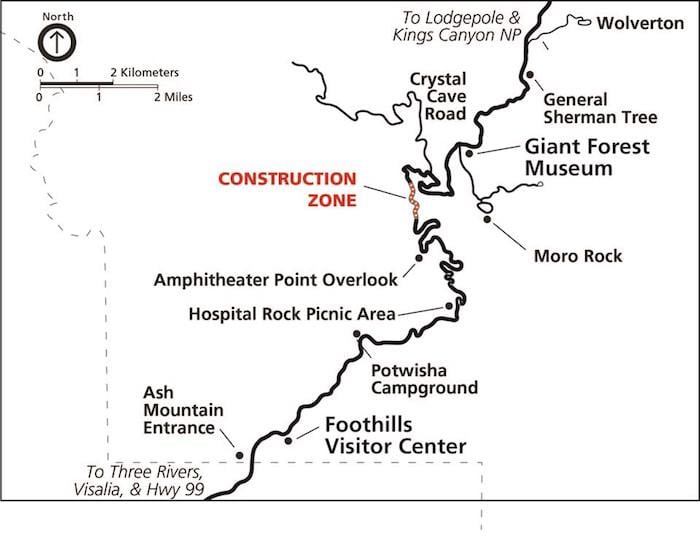

As with many large parks, keeping up with road repairs is an annual task for Sequoia National Park, where visitors routinely run into traffic delays along the Generals Highway, which was built to 1930s standards/NPS

Sophie’s Choice

The Park Service projects a steady decline in road and bridge conditions unless funding patterns change. Annual priority lists direct money to the most critical projects. Others have to wait.

That means that visitors driving into Everglades National Park through vast carpets of grasses and cypress trees, have to swerve around road bumps and eroded surface.

“When it’s your ‘front face’ -- and you’re asking people to pay an entrance fee -- and the first mile and a half to the entrance is unpaved as well as several miles beyond it – it’s not a good starting point,” said Deputy Superintendent Justin Unger.

Arizona’s Saguaro National Park got money to rehabilitate weakened retaining walls that support the scenic Cactus Forest Loop Drive last year, but had to go without crack and slurry seals that would stave off the need for expensive repaving, leaving roadway more vulnerable to heavy monsoons, said maintenance chief Jeremy Curtis.

Mineral King Road, the jump-off for trailheads to half of Sequoia National Park wilderness, will wait until at least 2023 for $17 million it needs to rehab its turnouts and road base, drainage structures, shoulders, and failing retaining walls, and do it in a way, Smeck said, “to preserve the scenery that people are coming to enjoy.”

Too Big to Fail?

Most formidable are the “mega projects,” any one of which would eat up the allocation of funds the Transportation Department provides for park roads each year.

Denali National Park awaits $25 million to build a bridge over the Toklat River, replacing a causeway that has caused changes in river dynamics, creating an unstable riverbank near visitor facilities.

Also on the mega-projects list is Zion National Park’s heavily used shuttle bus network, a crucial transportation system serving a massive surge in visitors, now at 4.5 million a year. The overloaded buses damage the roads, which weren’t built for their weight, and the aged fleet itself needs to be replaced with electric vehicles. “It will take a ton of time to replace our buses one at a time,” said Zion management assistant Cindy Purcell. ”Right now they are packed full, working at their peak capacity.”

In Yellowstone, routes that carry visitors to geothermal sites, waterfalls, and wilderness require an astounding $1 billion worth of reconstruction, according to the mega-project list. The park is about halfway to modernizing its 254 miles of main roadway, including adding shoulders, but at current funding levels it will take 75 years to finish the work, said Superintendent Dan Wenk.

“It’s a safety issue,” he said. Yellowstone is still more fortunate than many parks because its robust entrance fees can be used for maintenance projects, Wenk said, adding, “I don’t think you’ll ever not have some level of deferred maintenance.”

Referencing the overall backlog, including roads and other park assets, he said, “However, the level we have is certainly outpacing our ability to deal with it.”

Roads in Prince William Forest Park are crumbling away/NPS

Support for this reporting was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts

Previous articles in this series:

Traveler Special Report: Closing The National Park System's Maintenance Backlog

Traveler Special Report: Some Friends Groups Asked To Provide "Margin Of Survival"

Traveler Special Report: Maintenance Woes Blocking Access To Parts Of National Park System

Traveler Special Report: Historic Sites And Structures Affected By Maintenance Backlog

Traveler Special Report: Antiquated Wastewater, Sewer Facilities Go Wanting In National Parks

Traveler Special Report: Backlog Of Maintenance Needs Creates Park Risks

Add comment