Metate Arch, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument/BLM

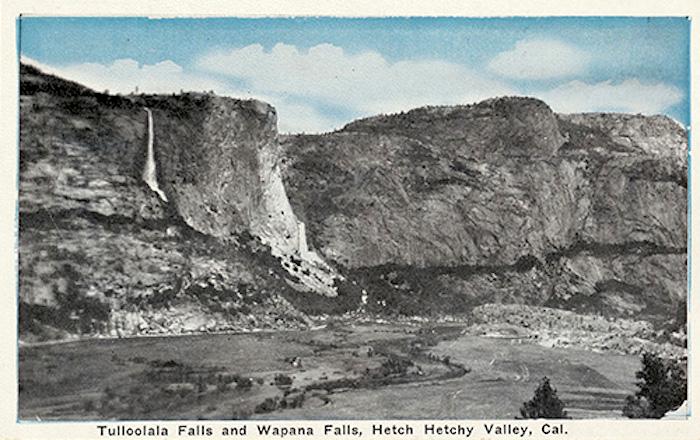

Early in the 20th century there was a fight over the fate of the Hetch Hetchy Valley at Yosemite National Park. Would it remain an amazing, waterfall-rimmed valley that so very well complemented the Yosemite Valley, or would it be given over to a reservoir to meet San Francisco's utilitarian needs? The battle for wildness, of course, was lost at Hetch Hetchy.

Today the battle is being repeated in Utah, where wildness and sacredness at Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in southern Utah are being tossed aside not so much for utilitarianism as for profiteering.

The battle for the Hetch Hetchy Valley was waged for seven years, from 1907 until the last month of 1913 when President Wilson signed the bill that cleared the way for the O'Shaughnessy Dam, which took another 10 years to complete. None other than John Muir helped inaugurate the campaign for Hetch Hetchy's wilderness, writing that "everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike."

In his classic book, Wilderness and the American Mind, Roderick Nash clearly outlined the battle lines, one peopled by financial interests and the other by preservationists.

"(i)s it never ceasing; is there nothing be to held sacred by this nation; is it to be dollars only; are we to be cramped in soul and mind by the lust after filthy lucre only; shall we be left some of the more glorious places?" one man testified to the House Committee on Public Lands during hearings in San Francisco early in 1909.

Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Forest Service who was at odds with Muir over preservation of wild lands, laid out the debate to the House committee: "whether the advantage of leaving this valley in a state of nature is greater than ...using it for the benefit of the city of San Francisco." Of course, he concluded, the city's need was greater than the valley's beauty.

"The fundamental principle of the whole conservation policy is that of use, to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people," said Pinchot.

Postcard view of Hetch Hetchy Valley before it was dammed and flooded.

Here in the 21st century Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke at times seems to hold somewhat to that view.

"I fully support multiple use of public lands, but multiple use is about balance and knowing that not all areas are right for all uses. There are places where it is appropriate to mine and places where it is not," he said.

The setting where Zinke made those comments was Montana's Paradise Valley, just north of Yellowstone National Park, and he made them in withdrawing more than 30,000 acres of nearby federal lands from mining for 20 years. Not too much time passed after the Interior secretary expressed a similar view when he moved to protect another area from drilling, the Badger-Two Medicine just west of Glacier National Park. Just this past Tuesday attorneys for the Interior Department announced that they would challenge a federal judge’s decision to reinstate the last remaining oil and gas leases in the Badger-Two Medicine.

Yet Secretary Zinke, who hails from Montana and understandably has an affinity for that state, doesn't share the same concern for Bears Ears or the Grand Staircase, as he worked with President Trump to shrink the two monuments by a combined 2 million acres. While the secretary said the substantial revisions to the monuments' boundaries had nothing to do with freeing up land for energy development, a review by the New York Times of Interior Department communications made clear that the redrawn lines "focused on the potential for oil and gas exploration."

The internal Interior Department emails and memos also show the central role that concerns over gaining access to coal reserves played in the decision by the Trump administration to shrink the size of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument by about 47 percent, to just over 1 million acres. -- New York Times

Whether driven by the rapaciousness of the extractive industries, political favors, or presidential spite, the current effort to shrink these two monuments is just the latest example of disregard for the value of wild lands and the strength they can offer humanity. The similarities to the battle over Hetch Hetchy can't be ignored.

Wilderness used to be undiscovered or passed-over land. But in the light of our present capacity for modifying nature, we must understand that the existence of wild country reflects self-imposed ethical restrictions on our capacity to control, exploit, destroy, and grow. As such, wilderness is the best physical and intellectual environment for learning that, if sustainability is a concern, less can indeed be more. We do belong, but not everywhere. To choose not to inhabit part of the planet demonstrates that we have finally understood what the ecologists have been trying to tell us for a century: that we are members, not masters, of the life community. -- Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind.

Comments

Excellent article and excellent comparison. Thank you, Kurt.

Good research and well presented.

Hetch Hetchy can and should be restored. To learn more, visit hetchhetch.org.