Continued retreat of tidewater glaciers at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve could force park staff to choose between protecting Johns Hopkins Bay for seal pupping or to open more of it up for cruise ships./Kurt Repanshek file

Hot Times in the North

By Rita Beamish

Editor’s note: As delegates from nearly 200 countries gathered for the recent international conference on climate change, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres decried the “utterly inadequate” global response to the crisis so far. He warned that the “point of no return is no longer over the horizon” but that “It is in sight and hurtling toward us.”

Nowhere are the consequences more visibly “hurtling,” and landing, than in Alaska. And in the northern state’s national parks and preserves, that means growing pressures on the very resources the National Park Service is charged with protecting.

When Jeanette Koelsch was a kid in Nome, Alaska, her clown makeup froze on her face as she traipsed through the cold in an oversized Halloween costume she’d wrestled over her bulky snowsuit.

“Now, when I take my son trick or treating, it often rains. He can wear a sweater and rubber boots,” says Koelsch, superintendent of Bering Land Bridge National Preserve. She references what everyone knows: Alaska is a lot hotter than it used to be, its temperature rising twice as fast as the warming globe’s average increase since the mid-1900s.

The scary specters worrying Koelsch these days thus have nothing to do with Halloween. They center on rapidly eroding coastlines washing away archaeological artifacts, vanquishing the chance to learn from them and honor their history; habitat changes upending wildlife patterns; shorter snow seasons and melting sea ice hindering subsistence practices that have sustained native cultures for thousands of years.

These shifts affect the very cultural, natural, and subsistence resources that Bering Land Bridge -- and its neighbor to the north, Cape Krusenstern National Monument – were established to protect. And it’s a dynamic playing out in national parks across Alaska. Treasured lands, waters, and cultural resources that the federal government vowed to protect for future generations are being altered and even destroyed by the warming planet.

Change is both subtle and dramatic: from the global-warming poster children -- melting glaciers -- to marine life shifts that ripple up the food chain. Lifeless seabirds by the thousands have washed up along the coasts, while other species are appearing where they’ve not previously been seen. Change happens as fast as the crash of a calving glacier, and as gradual as the vegetation shifts when ice-rich permafrost thaws into soupy mush. It’s happening now, and it’s speeding up.

Climate envelope model predictions for tundra (top; red) & forest taxa (bottom; blue) based on (A) and (D) current (Now), (B) and (E) 2050s, and (C) and (F) 2070s climate projections. The color gradient reflects areas of low (light) to high (dark) diversity. Distribution of diversity reflects compilation of predictive maps for 12 boreal and 7 tundra/alpine-associated species. Black lines provide a guideline to the extent of ≥50% of the diversity within boreal and tundra biomes./NPS

National Park Service scientists are tracking all of this – counting bird carcasses, measuring glaciers, monitoring caribou movements, and studying fish patterns -- to nail down impacts in Alaska parks and determine how, or if, they can adapt to climate change. Teasing out “normal” dynamic fluctuations in the volatile Alaska wilds is part of the challenge of illuminating whether anomalies in the record-breaking 2019 summer heatwave are a window into the future hot North.

“For us, things are going so quickly,” said Koelsch, noting the big-picture challenge: “How does the Park Service adapt to these issues in a way that mitigates impacts, that provides for access, that preserves subsistence and cultural resources, and protect natural resources?”

The question is only becoming more pressing. Just a partial litany of what Park Service scientists are tracking hints at the magnitude of change in these cherished – and environmentally crucial -- lands and waters:

- In Arctic national parks, lakes are draining as thawing of frozen ground opens new channels, with vast ecosystem implications. In 2005-07 and in 2018 following exceedingly warm years, dry-ups included six large Bering lakes that were habitat for the rare yellow-billed loon, scientists report. Barren mudflats, bereft of loons, remained.

- The virtual disappearance of the Bering Sea’s “cold pool” has shifted fish distribution. Snowcrab biomass was reported down 45 percent 2010-2018, while Pacific cod and pollock, more typical in warmer waters, increased in the area, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- At Cape Krusenstern, evidence of more than 5,000 years of human occupation – house remains, tools, animal bones -- is slipping into the sea as frozen bluffs thaw, protective sea ice declines, and battering storms take their toll, undercutting the park’s mission to preserve and interpret this archaeological record and protect Arctic ecosystems and subsistence resources.

- Sea stars, a vital predator species that keeps nearshore organisms in check, have plummeted in number since 2014, including along the coasts of Kenai Fjords and Katmai national parks. The virus-caused “wasting” epidemic has coincided with warming coastal waters, although scientists have not nailed down the specific triggers in the web of pathogens and environmental stressors..

- Ocean acidification fed by carbon dioxide absorption has pushed Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve to the “threshold of fundamental ecosystem changes,” its superintendent says. Acidification damages shellfish crucial to the marine ecosystem by making it difficult for them to grow their protective shells.

- NOAA scientists have identified a huge new “blob,” recalling the destructive 2014–2016 marine heatwave that caused massive marine die-offs and toxic algal bloom proliferation.

- Melting sea ice measured at a record Bering Sea low in 2018, about 10 percent of normal, and 2019 is nearly as low. NOAA made an “unusual mortality” declaration for ice seals when 282 dead seals were found between June 2018 and September 2019 in the Bering and Chukchi seas, five times the average and a concern for native people who rely on the marine mammals for food, clothes, and subsistence culture.

- Even human waste on the continent’s highest summit -- tons and tons of it -- is affected by warming. Deposited by Mount Denali climbers and frozen for decades in the ice, the old poop is making its way, over time and via glacial melt, to the downstream watershed. The Park Service these days requires climbers to carry poop cans in and out, but melt is expected to flush out the old waste in the coming decades.

Big Hungry

In the shadow of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve’s icy wonder, the bears drifted into the tiny gateway community of Gustavus this past summer. Not just the usual one or two, but 14 of them in a matter of weeks -- skinny, hungry, rummaging in gardens and casing chicken coops.

“They had no body fat,” explained Glacier Bay Superintendent Philip Hooge. In a record hot and dry summer, the bears’ salmon diet was elusive. Streams in the cold rainforest environment warmed – bad for salmon survival due to insufficient dissolved oxygen – and without the area’s typical rains and drizzle, some waterways were barely flowing, he said.

“I’ve been here 25 years. The number of clear days we’ve had – I’ve never seen anything like this,” Hooge said as the trend continued into September, dry months compounding the worrisome march of warming.

So while travelers -- visiting at a rate of 600,000 cruise ship passengers a year -- gloried in sunny, clear-sky views of Glacier Bay’s icy cliffs and crashing ice chunks, Gustavus residents worried about their shallow wells drying up.

And the fires that swept Alaska with unusual ferocity this year sparked what-if concerns, though they did not reach Glacier Bay. “We’ve never burned here,” Hooge said. “This is not a fire-adapted landscape.”

Rivers of Ice

Glacier Bay’s park mission includes ensuring access to tidewater glaciers, dynamic rivers of ice that terminate in tidal bodies. Scott Gende, Glacier Bay senior science advisor, posits that shrinkage by some tidewater glaciers ultimately could increase visitor pressure on Johns Hopkins Glacier, where protecting an important pupping site for seals is so vital that the park already restricts a disturbing influence, cruise ships, there.

“The conflict between resource protection and the mandate to allow visitor experience comes more to the forefront,” Gende said, adding, “Ten years ago this was not even on the radar screen.”

Will climate change force the Park Service to choose between visitor enjoyment -- cruise ships at Glacier Bay National Park -- or natural resources protection?/Kurt Repanshek file

Distinct from tidewater glaciers, Alaska’s sprawling land-terminating glaciers are a key climate change barometer. Two-thirds of all ice-covered areas in Alaska national parks are in massive Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve -- glaciers as thick as 3,000 feet and as big as the state of Rhode Island.

In Kenai Fjords National Park, where icefield coverage is the size of Los Angeles, Exit Glacier’s retreat continues to offer a front-row seat to climate change – but visitors must walk increasingly further to see it. Its retreat rate more than quadrupled, averaging 191 feet a year from 2013 to 2018, compared to its 1815-2018 rate, park measurements show. Now recessed 1.67 miles overall, it’s no longer visible from the viewing pavilion, hemmed by a sea of trees and shrubs where the vast glacier once sprawled. Extending the walking path over the years, the park makes access a priority.

“What makes it so iconic is that because of the access, people observe the change itself. They don’t have to look at data,” said Deb Kurtz, the park’s physical science program manager.

Michael Loso, a Wrangell-St. Elias park geologist who savors his office view of majestic, ice-locked Mount Blackburn, says glaciers will cling to very cold, high mountains for hundreds of years in places like this. But the rapid melt is “way more than you would expect” in normal glacial retreat-and-advance dynamics, and affects all plants and animals in ways not yet fully understood.

“Watching the glaciers shrink, it really … strikes at what to some people is the heart of what the park is about,” Loso said. When climate analysis looks to distant future outcomes, he adds, “A big part of the message here is that it’s happening.”

Short-tailed shearwaters, Ikpek Lagoon, Bering Land Bridge National Preserve./NPS, Jason Tucker

Species in Trouble

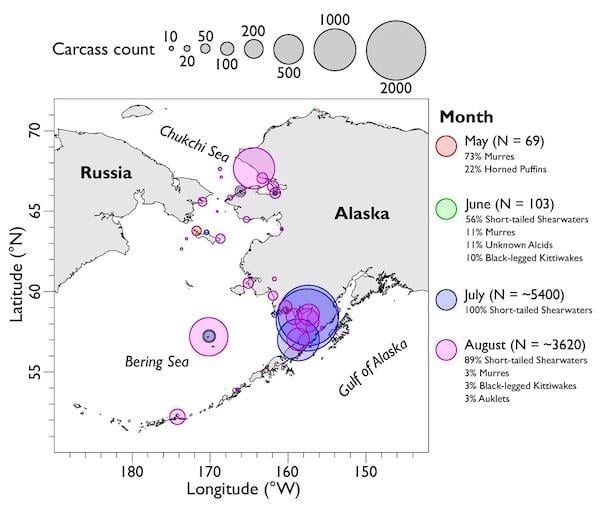

A disturbing report reached NPS marine ecologist Heather Coletti in 2015. A retired government biologist had come upon a startling sight: an estimated 8,000 bird carcasses on the shores of Prince William Sound. It turned out to be a die-off across the north Pacific, coinciding with warmer waters and “unprecedented in its scale, spatially and numerically,” Coletti said.

Each year since, massive seabird die-offs have triggered alarm in Alaska and Russia, including along national park coasts from Cape Krusenstern to Katmai, Kenai Fjords, and Glacier Bay: murres, puffins, shearwaters, auklets, and kittiwakes are all part of the toll. Especially troubling is that these birds are indicators of ocean health.

“We have known these systems are changing, but it was such a drastic response and so widespread -- it’s a bit frightening,” Coletti said.

Tests reveal starvation as the culprit. “Why they are starving is the next question,” she said. “There are likely lots of drivers at play”: Prey fish are known to grow less in warmer waters and thus may not meet birds’ caloric needs; warming waters may drive away cold-water fish they eat; large fish with metabolisms raised by warmer water might outcompete birds for the prey; birds may be exposed to biotoxins from algal blooms thriving in warmer water.

“Everybody recognizes that interconnectedness,” said Coletti. “It’s not like it’s hot and then they die. It’s lots of shifts in the food web.”

Counts of seabird mortalities across Alaska from May - August 2019./Map provided by Coastal Observation Seabird Survey Team coasst.org

In the intertidal zones, her research finds “potentially cascading community level effects” in warming waters of Prince William Sound and off Kenai Fjords National Park, Kachemak Bay, and Katmai National Park. Small mussels are declining with the loss of their algae habitat, while large mussel density has increased with the devastation of their sea star predators. Ripple effects likely will extend to species like sea otters and ducks.

“Salmon die-offs were not reported within national park boundaries,” noted NPS aquatic ecologist Krista Bartz, “but they were observed nearby, from Bering Land Bridge National Preserve to Kenai Fjords.”Fish in warming lakes and streams are struggling, too. Large numbers of salmon died en route to Alaska spawning grounds in 2019 as water temperatures soared beyond 70 degrees Fahrenheit, well above the preferred 45-to-55 degree range.

Alaska parks did see die-offs of other fish, such as northern pike, during the heatwave, as well as delays during this year’s heatwave in the upstream salmon migration – a problem that affects not just spawning salmon but also species that rely on them for food.

"It’s hard to know how it’s going to pan out in the end because it’s very complicated,” with unknowns about how warming will change the local salmon population habitats, Bartz said.

Slippage Underfoot

In Denali National Park, the workhorse, 92-mile road that each year carries hundreds of thousands of tourists took a drubbing last summer at Polychrome Pass, in the benignly named Pretty Rocks area. Some 300 visitors traveling in 17 buses were stranded temporarily when a cascade of mud and rock blocked the steep mountainside roadway, slippage spurred by the wettest summer in 95 years of record, park scientists say, on top of a continuing destabilization as the underlying permafrost thaws.

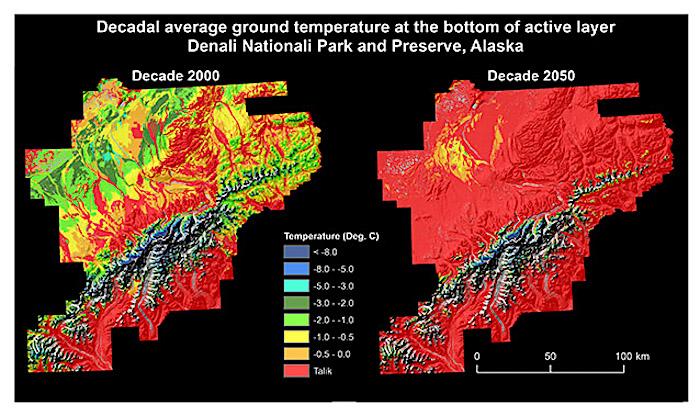

Permafrost – permanently frozen ground -- underlies nearly 40 million acres of national park lands in Alaska, about the size of Florida, notably in the five Arctic parks and in Wrangell St.-Elias, as well as in Denali. Warming is expected to reduce Denali’s near-surface permafrost over the next half century to 6 percent of the park’s area, from the current 51 percent, according to Park Service and University of Alaska researchers.

Of some 150 unstable sites on the Park Road, Pretty Rocks is the “problem child,” relentlessly encroaching even after it’s shored up, said park geologist Denny Capps. Its movement reached two inches a day as of this fall, overlapping “a very high-ranking, debris flow and rockfall hazard,” he said.

“If the situation continues to worsen, eventually we will not be able to maintain the road at this location without major engineering solutions” -- whether rerouting, installing a bridge, or blasting the area, solutions that all have their political, financial, and environmental problems, he said. The park has yet to decide on a long-term solution, but it is stepping up planning, monitoring, and maintenance for the coming year.

Denali staff collecting GPS data at the Pretty Rocks landslide near mile 45 of the Park Road on March 22, 2019. The survey rod she is holding, 6.5 feet tall, is placed near centerline of the road and shows the amount of displacement since September 14, 2018./NPS, Denny Capps

Denali isn’t alone with permafrost problems. Melting of this thick layer of frozen earth is creating slumping and sliding in places such as Noatak National Preserve and Gates of the Arctic National Park. The result has left thousands of deep depressions and slope failures, which then release greenhouse gases that had been locked in the ice for centuries. Park habitat is further altered as lakes draining through channels created by the slumping send sediment and siltation into other water bodies.

Populations at the Forefront

Alaska’s subsistence populations are living it all first-hand.

“We are already at a critical juncture of sea ice loss that already has started a cascading effect on fish and wildlife,” increasing hunters’ travel distances for ice-dependent mammals, Kawerak, a Bering Strait-region tribal consortium, wrote to the Senate Indian Affairs Committee on September 9.

Eighty-six percent of native villages are threatened by flooding and erosion, a 2003 U.S. General Accounting Office report found. Roads buckle, power poles sink in softened earth and structures topple as permafrost ground goes gelatinous. With protective sea ice forming later in the year, village coastlines are left susceptible to the increasing ferocity of pounding waves and storm surges. Entire villages are working on relocation in the face of inundation.

Escalating ship and tanker traffic through newly navigable Arctic waters has heightened worries about pollution, oil seepage, and ships striking marine mammals or impacting them with engine noise.

“Our carbon footprint is so very small but we’re feeling the impact of climate change by a factor of two – twice as many impacts as the folks in the lower 49,” said Austin Ahmasuk, marine advocate for Kawerak. “Impacting our food security, it’s transforming who we are … We’re seeing all these things they said would happen in 2050 -- they are happening now.”

The temperature values indicate presence of near-surface permafrost. The red color identifies areas with Talik (i.e., unfrozen ground above permafrost).

Noting the Arctic’s particular sensitivity to warming, Jon Jarvis, former head of the Park Service who was once superintendent of Wrangell-St. Elias, said unprecedented impacts like fires of unparalleled size and intensity are evident in Alaska and transforming the landscape. For instance, he said, “You can see the climate changes as forests spread and become established over these areas of melting permafrost and receding glaciers.”

Old paradigms of park management will need to change, Jarvis told the Traveler. Aside from carbon-emission reduction, he said, the Park Service must double-down on broad strategic management that starts with scientific and traditional knowledge and includes public education.

With ecosystems changing in ways not yet fully understood, “You can only do so much,” for strict conservation, he added. “We are left with adaptation. We still have a mission, and it’s for future generations. If we want to maintain the parks in as unimpaired a status as we can … we have to be smarter, use science and use the best strategies -- some at landscape scale, some protecting refugia … even some assisted migration to allow some species to survive,” he said. “In some cases, we may have to say goodbye.

“The parks will still be there. It’s just they will be different.”