How severe are the impacts from seismic oil exploration in Big Cypress National Preserve?/Kim O'Connell

A stark beauty is sweeping across Big Cypress National Preserve. It’s early March, and red spikes that signal the erupting bracts of the cardinal airplant are poking out from countless numbers of these epiphytes that have latched onto the trunks of dwarf cypress trees, a remnant of Florida’s once vast old growth forest.

Everywhere we look the cypress trees, some of which might have taken root here 1,000 or more years ago, are shouldering one or more of the colorful bromeliads that in the coming weeks will festoon the forest with their floral spikes. Here in the northern reach of Big Cypress, it’s apparently too early, or too late in some cases, for many of the preserve’s three-dozen orchid species to further brighten the kaleidoscopic revelry, though the bromeliads are doing their best to add some fiery contrast to the swamp’s greens, greys, and mud tones.

As we slosh through ankle-deep water across the marl prairie, passing rotund cypress domes and then hardwood hammocks with their leafy cocoplums, fronded sabal palms, live oaks, and other woody species, we encounter scars on ground. Twenty or more feet wide in places, and running roughly 100 miles, these are the footprints of oil exploration conducted in 2017 and 2018. Some sections of these “seismic lines” are regaining their vegetative cover, others bear rutted troughs unnaturally holding water; certain sites are practically devoid of vegetation despite the preserve’s subtropical climate and highly diverse botanical collection.

As the preserve is a “split estate” – the National Park Service owns the surface of the more than 720,000-acre landscape, while the mineral rights are privately owned – energy exploration and possible development were allowed in the enabling legislation that in 1974 made Big Cypress the country’s first national preserve. However, and this is the flash point that continues to fester nearly a half-century later, the legislation also gave the Park Service the authority to ensure that such exploration does not impede the reasons the preserve was created in the first place.

You can’t think too narrowly when assessing the impacts of what has been done to the surface of Big Cypress. The preserve is key to the health of the greater Everglades ecosystem, a sprawling area of South Florida that has been cut down, divided, drained, and developed for the past century. This ecological upheaval has significantly and repeatedly interrupted the sheet of water that flows from Lake Okeechobee through the “river of grass” down to Florida Bay, Biscayne Bay, and out west to the Ten Thousand Islands and Florida's west coast, impacts that now the state and federal governments are trying to reverse with a billion dollars worth of restoration projects.

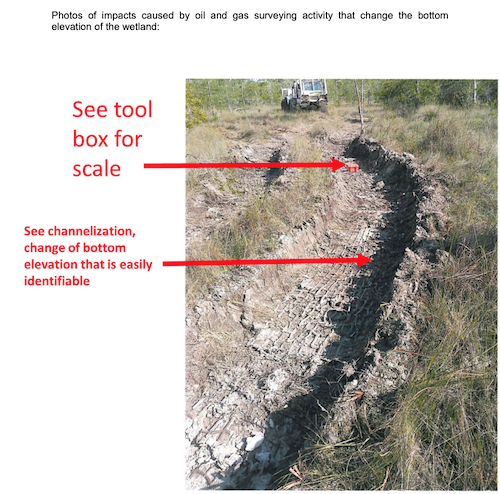

A good chunk of that money is being spent to raise portions of the Tamiami Trail, the road also known as U.S. 41 that connects Tampa to Miami, to allow water to flow unimpeded in places to the south. Meanwhile, the east-west running seismic lines created by Burnett Oil Co. constitute smaller, but nonetheless significant, impediments to the water, say conservationists. They’re obstacles that the U.S Army Corps of Engineers determined are adversely impacting Big Cypress, so much so that it concluded Burnett was in fact involved in “mechanized land clearing, ditching and channelization,” activities that “caused an impact that resulted in a change in the bottom elevation of the wetland, that the activity caused an identifiable individual and cumulative adverse effect on aquatic function, and that the survey had the adverse effect of degrading a water of the U.S.”

With that finding, the Corps told Burnett in a letter sent March 6 that the company would have to coordinate any future survey work “with the Corps in accordance with the Clean Water Act. A permit will be required of you unless and until you can demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Corps or Environmental Protection Agency, prior to commencing the activity involving the discharge, that the activity would not have the effect of destroying or degrading any area of waters of the United States.”

Exploring for oil and then possibly moving into widespread development with drilling rigs, jack pumps, and spider webs of support roads understandably raises concerns of impacts to the preserve proper, as well as the surrounding Everglades ecosystem.

This is an ecosystem with rare woodpeckers that live in family groups, with youngsters helping to raise their siblings. A subspecies of panther (listed as an endangered species more than five decades ago) has tenaciously survived despite the steady urbanization of Florida. More than 30 species of orchids grow in Big Cypress, perhaps most notable among them the ghost orchid that snakes its roots around the trunk of its host tree, anchoring its beautiful flowers. And there is the Everglades dwarf siren, a curious, bushy-gilled salamander that can grow up to 10 inches long.

Wood storks, an endangered species, live in Big Cypress, as do the red-cockaded woodpecker (endangered), the Everglade snail kite (endangered), Audubon’s Crested Caracara (threatened), the Eastern Indigo snake (threatened), and the American alligator (threatened). The preserve also provides important habitat to numerous other rare and federally endangered species of plants, birds, bats, and butterflies. The state of Florida, meanwhile, lists nearly 70 plant species within Big Cypress as endangered, and if you include threatened species, the state’s tally reaches 100 for the preserve.

Here, too, are nonnative Burmese pythons, lizards, and species of vegetation that are routing the natives, but that’s another story.

Cardinal airplants, epiphytes, are listed as endangered by the state of Florida. They anchor themselves to dwarf cypress trees in Big Cypress/Kurt Repanshek

Towards the end of the 20th century and early in the 21st the Interior Department made efforts to purchase the mineral rights from the Collier family, which became Florida’s largest landowner and developer after patriarch Barron Collier, who made his initial fortune in advertising, and his wife settled in the Fort Myers area in 1911. Late in President Clinton's second term and again during the first term of President George W. Bush, Interior considered buying the mineral rights, but the effort proved impossible to come to a fair market value that all parties agreed upon. Estimates ranged from $472.5 million, a figure provided by Collier Resource Company’s consulting geologist, down to nothing.

“During this investigation we found nothing to indicate that minerals in South Florida Big Cypress National Preserve area have any significant value. To the contrary, several sources suggest that the mineral resources in Big Cypress National Preserve are worth little or nothing,” stated a report prepared by the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General in 2005. “(T)he Department (of Interior) faced considerable challenges to establish any value for the mineral rights in the (Big Cypress National Preserve), never mind a value that would be acceptable to (Collier Resource Company).”

In the end, Congress refused to fund a $120 million deal, which the Inspector General maintained was wrongly tilted in favor of the company. At the time, and in light of OIG's findings, there was some speculation that Collier, which hired Burnett to search for recoverable oil deposits, had only been pushing for the exploration permit to build overwhelming momentum and public pressure on Congress to acquire the mineral rights.

Come forward to 2020, and a handful of conservation groups urged Gov. Ron DeSantis, who earlier had announced plans for the state to buy 20,000 acres of Everglades wetlands to prevent oil exploration and possibly development, to have the state acquire the mineral rights at Big Cypress.

Seismic Impacts

Having covered this issue from a distance for the past decade, I headed to Big Cypress with contributing writer Kim O’Connell the first week in March so we could see for ourselves how visible the impacts were of Burnett’s use of ponderous “vibroseis” trucks that can weigh 30 tons to search for oil reserves. The vehicles, which some call “thumper trucks,” create ground-penetrating seismic waves by exerting all their weight onto a vibrating steel pad. Small instruments called “geophones” in turn receive the shock waves, and geologists use the waves to create three-dimensional maps of the underlying ground.

Our visit was incredibly timely, as the very day we went into the preserve the Army Corps of Engineers sent its letter (attached below) to Burnett’s president, Charles Nagel.

Calls to Burnett for reaction to the letter were not returned, and neither National Park Service officials at Big Cypress nor Rob Wallace, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Parks, responded to specific questions concerning the impacts we saw in the preserve. As for Collier Resources, in the past it has said Congress had several opportunities to acquire the mineral rights, and that the preserve’s enabling legislation allowed for oil exploration and development.

Pedro Ramos, the Everglades National Park superintendent to whom the superintendents of Big Cypress and Biscayne National Park report to, told me back in December that the Park Service was pleased with the efforts Burnett had made in reclaiming the seismic lines created in 2017 and 2018.

“We’re actually satisfied with it. We have to now let some time pass so that we can make observations with respect to how the resource actually responds to the work that they did," he said at the time. "And once we can make those observations and really get the story, the level of success of that work, then they will have to do some mitigation.

“I know that some of the environmental community folks are concerned about the speed at which that initial pass over to do the remediation was done. But from my perspective and from all the reports that I am getting out of the team at Big Cypress, we’re very pleased with the work that they did," Ramos told me.

Leading us into the field on March 6 were Mary James, an environmental consultant with Quest Ecology who had been retained by the Natural Resources Defense Council; John Meyer, a retired wetlands scientist who had spent much of his career with the South Florida Water Management District that manages water resources in the Everglades and now is a volunteer biologist for NRDC; and Melissa Abdo, director of NPCA’s Sun Coast regional office. They were heading out to double-check the impact findings reported by Burnett’s environmental consultant, Turrell, Hall and Associates, Inc.

We headed south from Interstate 75 under moody skies that altered throughout the day from mostly cloudy to mostly bright and sunny. Hiking across the preserve through its dwarf cypress forest, we alternated between splashing through ankle-deep water and a muddy gumbo to easy going on firm, dry soil, always with an eye out for snakes (cottonmouths and rattlesnakes are among the locals) and other fauna.

“If you know the plants, you know what’s happened to the land,” said Abdo, who holds a doctorate in conservation biology, as we walked into the preserve from Interstate 75. “We’re just seeing new channels cut across the landscape. …This was supposed to go back to pre-survey conditions.”

As she talked, she pointed to Eleocharis, a native sedge-type of grass known as spikerush growing in the water-covered prairie. Though not well suited to drier ground, we later would encounter immense new monocultures of this sedge growing in a seismic line where the vibroseis vehicles had left ruts that didn’t appear to have been suitably reclaimed as required by the Park Service permit and which now were holding water while the areas just beyond the seismic line were dry.

That standing water can also prevent cypress from coming back, Meyer pointed out.

“The cypress seedlings need to have dry land,” he said. “That’s why the elevation (of the reclaimed seismic line) is important. In areas that are worse, we should give the cypress a head start by planting.”

This alligator, estimated at 10 feet long, found the standing water in a seismic line a comfortable place to rest/John Meyer

At the first area they stopped to check the findings of Burnett’s consultant, the three scientists set up a grid to compare the topographic elevations inside the seismic line with those outside the line, and took a botanical census. The understanding heading into the project was that the seismic lines would be contoured back to their presurvey elevations, though NRDC officials have said the oil company's reclamation crews aimed for no more than a 3-inch differential.

“This should be a straight line if it was reclaimed correctly and also monitored correctly,” James told me while pointing to a printout of the elevations that depicted an undulating line. “In an environment where the vegetation distribution is so dependent on elevation and hydrology -- which is often guided by elevation -- you could have a dramatic shift in the plant community if the reclaimed elevations don’t match the natural undisturbed adjacent elevations.

“What we’ve seen is dramatic ruts were created by the seismic survey vehicles that ponded water for longer, which would be more suitable to a different suite of species than you’d find in the typical cypress strand. Within the impacted pathways, you might have ponded water for eight to ten months of the year, or even longer.”

Alison Kelly, a senior attorney with NRDC’s Lands Nature Program, told me that heavy rains in 2017 cut short Burnett’s fieldwork and that the company focused on exploration, not reclamation, when it returned in 2018.

“Basically, it wanted to maximize its time in the short dry season collecting oil data instead of complying with the reclamation requirements of its permits,” she said in an email.

In an emailed statement, Tim Hall, a principal and senior ecologist with Turrell, Hall, said that the firm is continuing to conduct monitoring of the seismic survey pathway reclamation activities in Big Cypress. “To date one initial monitoring event has occurred,” Hall said. “No definitive conclusions were made in that monitoring report except that future monitoring would be required to determine if the area was recovering as anticipated in the permits that were issued for the project. A second monitoring event is currently under way now that water levels have receded enough in the Preserve. Monitoring will be ongoing for at least the next three years to track recovery or lack thereof.”

Those are just some of the concerns environmentalists and conservationists have with how the seismic lines are erased. If not mitigated properly, they also could serve as firebreaks, impeding a naturally caused fire that can contribute to a healthy, diverse habitat as it burns across the landscape. Nonnative species that prefer water also could colonize the lines if they are not properly reclaimed, said James.

Another site we visited showed swaths of Eleocharis brimming from the seismic line, a dwarf cypress trunk roughly 8 inches across that had been chainsawed at ground level, and several inches of water filling the line. At a third site, an alligator estimated at ten feet long was enjoying a water trough that shouldn’t have been there.

Weighing The Impacts

As a national preserve, as opposed to a “national park,” Big Cypress is open to a number of activities not seen in national parks. Hunting is allowed, there is active oil production, though limited, and off-road vehicles travel hundreds of miles of roads in the preserve. So how significant is the impact of Burnett’s activities?

“I don’t think of it as a little area,” James told me during a break. “By the data that we’ve been provided, there’s been over 100 linear miles of impacted seismic lines of varying widths, 12 to 15 (feet) maybe the absolute minimum. But we’ve seen 30 to 40 (feet) in places where they’ve not gone in and out the same path or they were trying to avoid something.

“I forget the number of acres that accounts for, but at a minimum 200 acres of impact,” she continued. “That’s not all in one place, so it maybe doesn’t jump out and grab you if you’re standing in one place, but if you look at it on the full scale that it was conducted, I don’t consider that a small impact.”

Abdo, noting that Burnett has completed just one phase of an anticipated multi-phase project, said the ultimate amount of impacted areas could be staggering.

“The area that was proposed for the entire seismic exploration to search for oil and gas deposits was actually a size that was larger in its entirety than the entire national park units of Shenandoah National Park, Zion, or Biscayne National Park right here in South Florida,” she said. “That was the previously proposed area. And the area that we know has been impacted by the seismic exploration that was carried out in 2017 and 2018, that area is approximately 110 to 112 miles of these seismic lines, so that’s actually quite a massive area.”

James pointed out as we walked deeper into the preserve that this area of Big Cypress where Burnett worked is one of the most pristine areas of the preserve. While the groundcover will come back, she went on, she won’t live long enough to see the regrowth of cypress trees to pre-impact heights.

“We’ve lost a lot of old trees. Florida’s old growth,” she said. “They’re not very big, but it’s an atrocity in my opinion.”

Estimates of the number of trees that were cut down during the exploration range upwards of 400. Some of those trees, said Abdo, were in the 200- to 500-year-old range, and some research indicates that some of the trees might have been 1,000 years old.

Not to be overlooked, the NPCA official said, is that Big Cypress contributes an estimated 40 percent of the water to the “river of grass” that nourishes the greater Everglades ecosystem as it flows out to Florida Bay and the other estuaries.

“The impacts here within Big Cypress National Preserve can impact Everglades restoration,” Abdo said. “Taxpayers, our federal government, and the state of Florida have invested over $1 billion working to restore America’s Everglades right here in South Florida, and that restoration effort is what we know as the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, CERP. … It’s completely counter to that effort to be impacting such an important area in the greater Everglades ecosystem.”

Reacting to the Corps’ letter after we returned from the field, she said the Park Service needed to step up and protect the preserve from further damaging survey work.

“The Florida Department of Environmental Protection granted Burnett a permit for this project and the National Park Service, despite their mandate to protect Big Cypress, determined in 2016 that Burnett’s activities would have no significant impact on the preserve,” she told me. “Since then, Burnett Oil Company’s oil and gas exploration activities have dealt serious damage to Big Cypress. Their heavy machinery left deep scars across more than 100 miles of this priceless landscape, creating unnatural channels across iconic wetlands in America’s Greater Everglades ecosystem. Burnett’s vehicles tore down endangered flora, including more than 400 trees, many of them old-growth dwarf cypress harboring endangered orchids and bromeliads. There is no telling exactly how much damage this hunt for oil has done to the endangered Florida panther’s last remaining habitats.

“…This letter is a wake-up call. It is high time for the National Park Service to use their authority to protect Big Cypress from future seismic oil exploration proposals that impair the preserve’s natural and ecological integrity,” Abdo said.

Meyer, who spends a good number of his retired days in the backcountry of Big Cypress to monitor its health in the wake of the seismic work, holds out hope the impacts eventually will fade.

“I enjoy the challenge of trying to preserve what we have here, and to keep it what it is, which is just the incredible jewel that it is for South Florida and the nation,” he said during a break in the survey work. “I spent my career regulating wetlands, protecting them in some cases, and in other cases issuing permits for activities in wetlands, but this right in my wheelhouse for the type of thing I did before, trying to save what we had and make sure that the folks who are utilizing the preserve are doing it in the correct way and a way that my kids and grandkids will be able to enjoy it for a long, long time.”

To Meyer’s eye, it’s hard to say whether the impacts can be repaired, let alone entirely erased.

“What happened is a severe scar. Wounds heal over time, and we suspect that a good part of this will heal,” he allowed. “The cypress trees obviously were a keystone species here and we lost a lot of them as a result of this activity. So whether we get those back, time will tell. But we do think it was a long-term impact that probably could have been avoided.”

Additional reporting by Kim O'Connell.

Reader and listener support makes stories such as this one possible. Please donate today so we can continue to provide you with this sort of coverage of national parks and protected areas.

A copy of National Parks Traveler's financial statements may be obtained by sending a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: National Parks Traveler, P.O. Box 980452, Park City, Utah 84098. National Parks Traveler was formed in the state of Utah for the purpose of informing and educating about national parks and protected areas.

Residents of the following states may obtain a copy of our financial and additional information as stated below:

- Florida: A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR NATIONAL PARKS TRAVELER, (REGISTRATION NO. CH 51659), MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING 800-435-7352 OR VISITING THEIR WEBSITE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE.

- Georgia: A full and fair description of the programs and financial statement summary of National Parks Traveler is available upon request at the office and phone number indicated above.

- Maryland: Documents and information submitted under the Maryland Solicitations Act are also available, for the cost of postage and copies, from the Secretary of State, State House, Annapolis, MD 21401 (410-974-5534).

- North Carolina: Financial information about this organization and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at 888-830-4989 or 919-807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the State.

- Pennsylvania: The official registration and financial information of National Parks Traveler may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling 800-732-0999. Registration does not imply endorsement.

- Virginia: Financial statements are available from the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 102 Governor Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219.

- Washington: National Parks Traveler is registered with Washington State’s Charities Program as required by law and additional information is available by calling 800-332-4483 or visiting www.sos.wa.gov/charities, or on file at Charities Division, Office of the Secretary of State, State of Washington, Olympia, WA 98504.