A diorama of a polar bear and seal inside the Auyuittuq National Park Visitor Centre/Jennifer Bain

There was no getting into remote Auyuittuq National Park when I landed in Pangnirtung in that awkward stage of early winter, when it’s cold and dark most days and the sea and river ice hasn't yet fully frozen so it isn't safe to boat or snowmobile.

Instead, I headed to the park’s visitor centre to learn more about the Baffin Island community that lives in a fjord on Cumberland Sound and that’s famously near Mount Asgard where the opening ski and parachute scene of The Spy Who Loved Me was shot. The twin-peaked mountain — with flat topped, cylindrical rock towers separated by a “saddle” — is 30 kilometres (19 miles) away in the national park.

It was early December in Nunavut and the inukshuk — a structure made of stones piled on top of each other usually to mark important places — in the foyer of the weathered, pale green visitor centre was draped in festive garlands and topped with a Santa hat. A few steps away was a dramatic diorama with a taxidermied polar bear wearing a sparkly green garland and preparing to feast on a seal on real rock and sand in front of a painted ocean.

Parks Canada interpretation officer Matthew Nakashuk was on hand to share his enthusiasm for Pang and gently explain why day trips to Auyuittuq were out of the question. He consoled me with a look at some of the cultural, historical and archaeological artifacts that are showcased at Canada’s national parks and historic sites.

Interpretive displays in English, French and Inuktitut revealed that Baffin Island and Greenland were once connected but continental drift separated them amid volcanic activity that created massive lava flows. Ice didn’t build up on the nearby Penny Ice Cap and override mountain peaks during the Ice Age like it did elsewhere, and outlet glaciers let accumulating ice flow between mountains into lower valleys. That’s how Mount Asgard, Thor Peak and other local mountains kept their unusual shapes.

Almost all the soil here is permanently frozen, except for a thin surface layer that melts in summer and lets plants grow to battle strong Arctic winds blowing sand and snow crystals. “The survivors are tough, well-adapted life-forms,” read a sign beside photos of defiantly golden Arctic poppy and fuzzy Arctic willows.

Parks Canada interpretation officer Matthew Nakashuk in front of the visitor centre's Inuit mural/Jennifer Bain

A mural dominated the walls of the polar bear room, showing what I believe were those same yellow poppies in a summer scene with an Inuk woman kneeling by a mountain river in front of a skin tent, butterfly, caribou, geese, wolves and a Rock ptarmigan. The mural segued into a winter scene showing an Inuk hunter poised with a harpoon over fish and other marine life in front of an igloo and sled dog team, northern lights, polar bears and an Arctic fox.

On other walls there was a seal skin stretched out on a drying rack and, naturally, massive maps detailing the national park.

Auyuittuq (pronounced ow-you-we-took) is Inuktitut for “Land That Never Melts.” With craggy mountains and granite cliffs, it’s the most accessible of the territory’s five national parks and the most popular with hikers, skiers, climbers and backpackers. Outfitters with snowmobiles, dog teams or boats also lead day trips. Orientation sessions are mandatory before entering the park and so is de-registering at the end of a backcountry trip. Polar bears, avalanches, severe winds, flooding and rockfall are just some of the threats, and emergency shelters and outhouses are the only maintained services in the wilderness park.

National park visitor centres are often overlooked. They’re more than just a place to pay park access fees and buy fishing licenses, trail maps, books and souvenirs. It was at this one in Pang where I learned that had it been April, with its frozen sea and rivers and long hours of daylight, Parks Canada might have led me on a day-long boat and hiking trip to Ulu Peak or on an Arctic Circle snowmobile outing.

“These are just a teaser to get into the park,” admitted Nakashuk. “The scenery gets more dramatic as you get in deeper.” Ninety-eight per cent of visitors hire an outfitter out of Pangnirtung or the island community of Qikiqtarjuag. Only two per cent of people devote the four extra days needed to hike or ski in and out of the park, something that is discouraged. Those who camp typically stay three to five days.

The visitor centre doubles as an art gallery of Inuit soapstone sculptures/Jennifer Bain

Auyuittuq has a polar marine climate and its spring ski, snowmobile and snowshoe season usually runs mid-March until early May. The park becomes inaccessible when the sea ice breaks up in June and July. Hiking and climbing season, with access by boats on the incoming or high tide, typically runs late July through September.

While adventurous visitors have just begun to explore Auyuittuq in the last century, the Inuit and their ancestors have been using the region for thousands of years and maintain unrestricted access.

“In order to survive from the land, you have to protect it,” declares Mariano Aupilaarjuk — presumably a revered elder — in a display about the Fork Beard Glacier and the impact of climate change. “The land is so important for us to survive and live on; that’s why we treat it as part of ourselves.”

A circular chart showcases the Inuit year’s eight seasons, which includes season of the seal pups, season of the berries and season of the denning polar bear. It details how caribou, seal and Arctic char are harvested year-round, and what can be hunted, fished and harvested in other months.

Another display poetically describes Auyuittuq as “a land of ice, a dozen fjords, a hundred glaciers, an ice cap bigger than Prince Edward Island.”

The Inuit living in the Cumberland Sound had little contact with settlers until American and Scottish whalers arrived in the 1820s to hunt bowhead whales. People began to settle in Pang (“Place of the Bull Caribou”) in the 1950s, and the gateway community of 1,600 is now 85 per cent Inuit. It sees several hundred visitors a year, most from expedition cruise ships who don’t stay the night.

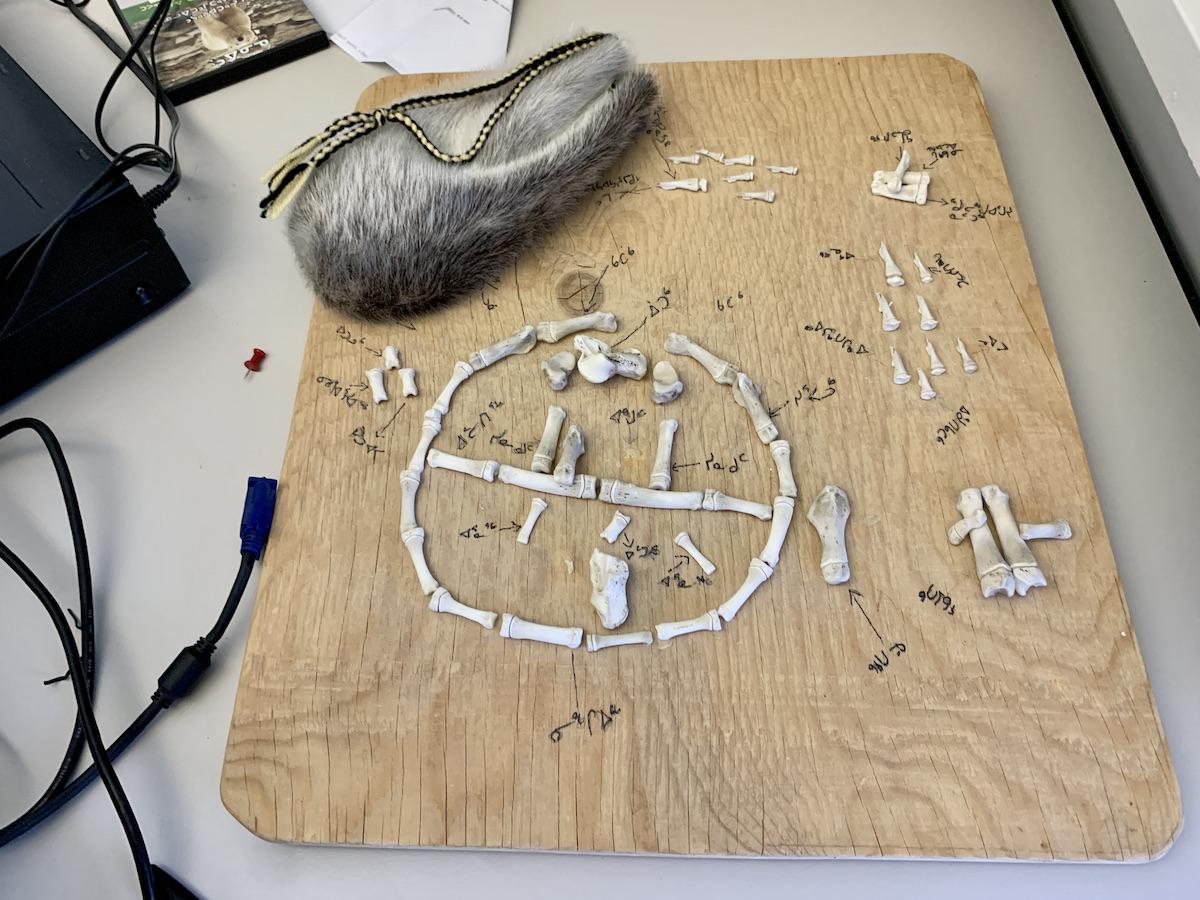

A traditional Inuit game made of bones/Jennifer Bain

The visitor centre’s staff meeting room is also open to explore, and signage details how the human history of Auyuittuq spans 4,000 years and how archaeological inventories of the park are ongoing. It delves into the Thule people, the ancestors of today’s Inuit who came here from Alaska as expert whalers with metal and stone tools as well as important technology for kayaks, dogsleds and hunting land and sea mammals.

This room has sea views and showcases soapstone sculptures by Inuit artists such as Jaco Ishulutak and Manasa Evic, as well as an intriguing traditional bone game called Inugaq that revolves around competing to create families, dog teams, sleds and igloos.

For such a small visitor centre, this one punches above its weight in showcasing the park and Inuit culture. After my visit, I puttered around Pang, visiting the commercial turbot fishery plant, two grocery stores with distressingly high prices, the Angmarlik Visitor Centre to learn more about the Thule and modern Inuit, the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts to admire the famous tapestries and buy crocheted Pang hats, and the Hudson’s Bay Co. blubber station that was once used to process the fat and hides of whales and seals. I stuck close to town, on high alert for polar bears.

Mount Asgard and Auyuittuq National Park might have been too far away to even catch a glimpse of, but I flew away from the stunning hamlet dubbed "the Switzerland of the Arctic" with a vivid mental picture of them both and an impatience to return soon — in the appropriate season.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment