The Muldrow Glacier at Denali National Park recently began "surging" downhill. This shot by pilot Chris Palms is looking up the main stem of the glacier with Denali in the top left, McGonagall Pass in the upper right and the Traleika Glacier tributary coming in from top left. Sheer lines of broken ice and abundant crevasses are visible/ Chris Palms via NPS

A "spectacle of nature," in which the Muldrow Glacier in Denali National Park and Preserve has suddenly surged forward for the first time in more than six decades, has opened a scientific window for glaciologists to better understand the park's rivers of ice. Though highly unusual, the glacier's rapid movement is not believed to be linked to climate change, but rather due to the "unique nature of the structure and composition of the glacier’s ice, its surrounding rocks, and the topography it is moving through."

The event on the Muldrow Glacier, which originates high on the northeastern slope of Denali and flows north to form the McKinley River, was spotted last month by pilot Chris Palms of K2 Aviation during an overflight of the mountain. It was revealed Wednesday by the park. Since Palms' discovery, park scientists have begun a flurry of observations of this now rapidly flowing glacier.

“It’s a spectacle of nature, and especially interesting because it’s rare to have this kind of event on such a historically prominent glacier that is a centerpiece of Alaskan visitation,” said Guy Adema, deputy director for Natural Resources Stewardship and Science for the National Park Service and former glaciologist for the Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network.

According to park staff, "glacial surges like this are typically short-lived events where ice within a glacier can advance suddenly and substantially, sometimes moving 10-100 times faster than normal. This sudden surge has quickly and dramatically altered the appearance of the previously slow moving Muldrow Glacier, with heavy crevassing occurring throughout most of the length of the glacier."

Preliminary satellite radar image analysis of the Muldrow Glacier completed by University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers Mark Fahnestock and Bretwood Higman suggests the glacier is currently flowing at a rate of 10-20 meters, or 30-60 feet, per day which is about 100 times faster than normal, according to the park. This surge is believed to have begun sometime in January and is expected to continue for several months, a park release said Wednesday.

As a result, mountaineers planning to use the north approach to Denali this climbing season will likely be impacted. Route finding this spring may be nearly impossible due to unstable ice conditions and the dramatic increase in crevasse hazards. Additionally, there is a heightened risk of outburst flooding along the McKinley River beyond the terminus of the Muldrow Glacier. Outburst flooding can occur with no warning, and for safety reasons backpacking in these areas of the park may be restricted.

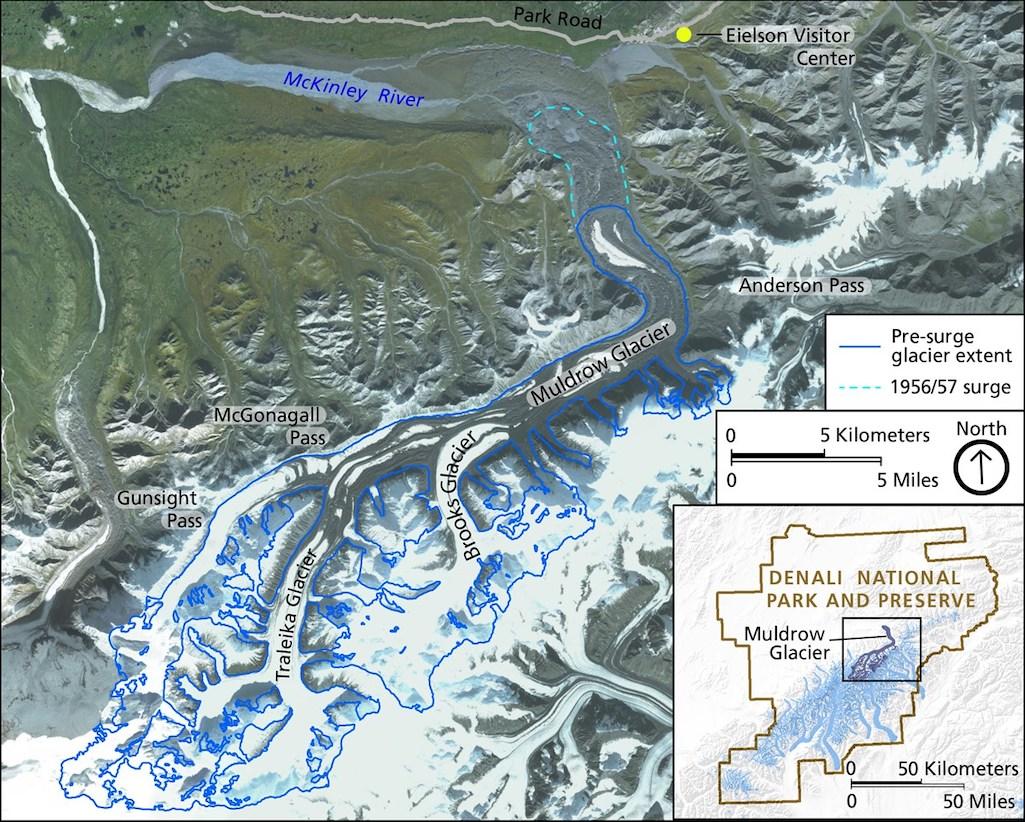

In a prior surge event during the winter of 1956-57, the glacier advanced just over 4 miles in a few months’ time.

Scientists had been anticipating this surge for a while now, as the glacier displays evidence of a 50-year surge cycle, but no one knew exactly when it would occur. Adema, who has studied the Muldrow Glacier for decades, is particularly interested in investigating this event more closely.

“I’ve been waiting for the Muldrow to surge for a long time," he said. "This is an incredibly exciting event to witness and to study!”

Map of the Muldrow Glacier and surrounding area. Imagery is Alaska SDMI SPOT 5 Mosaic Dataset (2010-2013), glacier outlines are from Randolph Glacier Inventory/NPS

Surges like this may be caused by the interplay of ice buildup at higher elevations over time, and supply of meltwater to the base of a glacier, the park said, adding that, "Due to the geometry of many surge type glaciers, ice accumulates and thickens on the upper glacier over many decades with only a slow flow or transfer of ice to the lower glacier. At some point during the quiet, accumulation phase, the mass reaches a threshold where the internal hydrology of the glacier is disrupted. Rather than running out at the terminus, meltwater is retained at the base of the glacier. The soft metamorphic bedrock that underlies the Muldrow, along with the massive quantities of retained water reduces friction and “floats” the glacier causing it to surge. Once a surge begins, positive feedback loops and momentum can often contribute to the speed and duration of the surge."

“The fact that it’s happening in a place that people know and care about makes it rather interesting,” said Adema. Overall, while it is estimated that only 1 percent of all the world’s glaciers ever surge, Adema points out that Denali is a bit unique in this respect.

“A relatively large portion of Denali glaciers are surge type due to the dramatic relief of the mountain," the glaciologist said. "The intermittent surging makes these glacier less ideal for monitoring the impacts of climate change, but are fascinating to watch when surges like this occur.”

Park scientists will continue to monitor and map this dynamic situation both during and after the surge event, with the hope of increasing their understanding of how glaciers in Alaska are changing.

The National Park Service also monitors the mass balance of a small set of glaciers in several national parks. Non surge type glacier dynamics are a long-term indicator of climate change. On the south side of Denali, opposite from the Muldrow, the Kahiltna glacier is a long-term index glacier that is slowly retreating. Overall, ice cover in Denali has declined by 8 percent since 1952.

Visitors to Denali National Park this summer should temper expectations of what they may be able to see without a backcountry excursion or overflight, however. Evidence of this surge is likely to be less dramatic when viewed from the Park Road or the Eielson Visitor Center, with only a bit more jumbled ice visible in the distance along the edge of the glacier.

More information on the surging Muldrow Glacier can be found at go.nps.gov/MuldrowGlacier.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment