Lake Mead continues to decline under the ongoing drought/Lighthawk, August 2020

Traveler Special Report: Drought, Heat Taking A Toll On National Parks In Southwest

By Jonathan Horwitz

Editor's note: The National Park Service plans for a warmer, drier future but record drought in the Southwest shows there’s no time to spare. National Parks Traveler is producing a multi-part series of articles this summer exploring the effects of climate change on the National Park System’s landscapes, wildlife, economics, and planning. Also, the text has been corrected from an earlier version regarding habitat conditions for bird species at Petrified Forest National Park. The NPS findings were projections, not on-the-ground observations.

Signs of summer were everywhere as I emerged from my partner’s vintage Subaru Outback on a recent car camping trip in California. The heat shimmering off the sunroof baked the car’s interior – making it unbearably hot and impossible to sleep any longer.

It was 9 a.m. and the car’s thermometer was already reading 91 degrees. It was Memorial Day Weekend in the Stanislaus National Forest, west of Yosemite National Park, and while the late-May holiday usually ushers in summer, this year’s warm temperatures and lack of rain made it seem the dog days were already here.

And it wasn’t just Yosemite. Across the West during the last week of May, temperatures were three to six degrees above normal, the Sierra snowpack had disappeared - measuring an astonishing zero percent of average - and in Utah things were so desperate that the governor called for divine intervention, asking citizens to pray for rain.

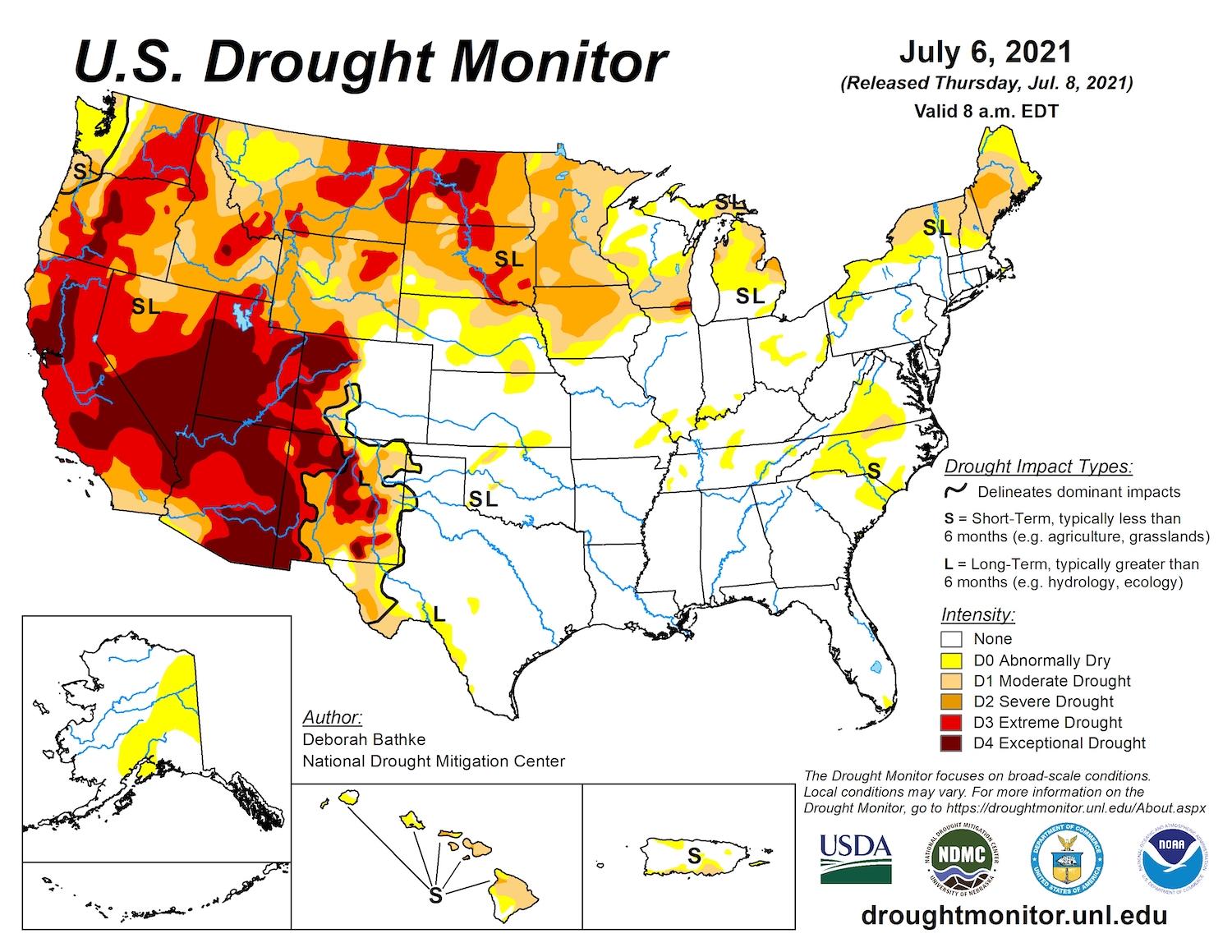

And, while an exceptional drought persists across the West and the High Plains, a moderate drought is affecting portions of the Eastern Seaboard, Hawaii, and Arctic Alaska.

In a 2021 climate adaptation report, the National Park Service warned that some plants and animals won’t survive the changing climate conditions, and said many more will compete for exceedingly scarce land and water resources. Additionally, the report says that park managers must consider changes to precipitation patterns when designing stormwater systems, drafting water resource management plans, and preserving historic buildings and significant roadways.

On the heels of the report and in the midst of a record drought, National Parks Traveler is exploring through a series of stories how arid conditions in the West are affecting parks' landscapes, wildlife, economics, and planning.

As the Park Service report pointed out, all Western parks are at risk, not only from the drought but from conditions created by it.

- Saguaro cactus in Arizona and Giant Sequoia in California, the parks’ eponymous species, are under threat from water scarcity.

- In the Grand Canyon and in Utah’s “Mighty 5,” the likelihood of more wildfires will challenge the tourism industry as well as the survivability of forest ecosystems.

- From the glaring dunes at White Sands National Park in New Mexico to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona, depleting groundwater reservoirs could jeopardize desert oases.

- At Petrified Forest National Park — better known for fossils than wildlife — climate change projections indicate that as many as 16 species that currently use habitat there could be forced out, while another 19 not currently found in the park could find the evolving conditions more suitable, NPS researchers found.

According to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, nearly half of the United States is experiencing moderate to exceptional drought conditions, which are expected to continue and expand through the summer/National Drought Mitigation Center

Series Focus Will Be On Water And Drought

NASA climate scientist Ben Cook uses tree ring data to study climate records dating back thousands of years. He says this year’s drought is highly unusual for its scope and magnitude.

“This is a rare type of event to have all these subregions in drought at the same time, and it really underscores how extreme this particular drought is,” Cook told the Traveler.

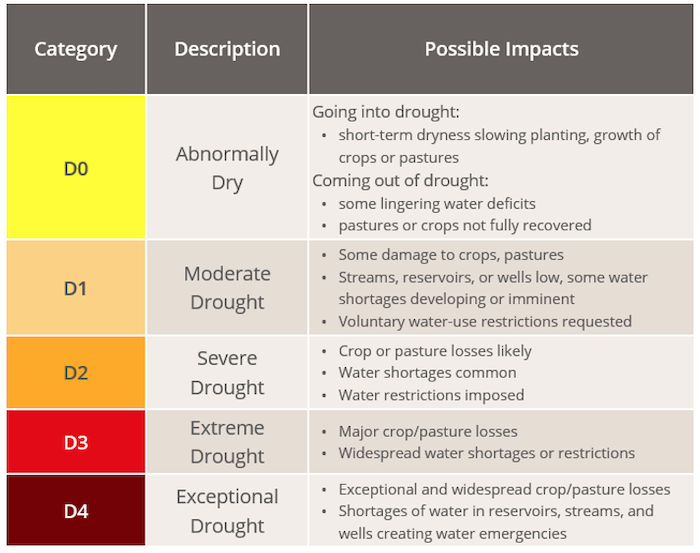

Conditions are most severe in the West. One-quarter of the region is labeled with the government’s highest category of drought, exceptional drought, or D4, which corresponds to an area experiencing widespread crop and pasture losses, fire risk, and water shortages that result in water emergencies.

Drought conditions are particularly series in the West/NOAA

Ninety-six percent of the region is experiencing at least abnormal dryness, which affects more than 58 million people. Diminished snowmelt from the Rockies threatens water cutbacks for California and Arizona, which rely on the waning Colorado River to grow food and quench the thirst of desert cities.

America’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, has dropped to an all-time low water level since Hoover Dam was completed in 1935. Since 2000, the water level has fallen by 140 feet.

It has fallen 20 feet since last summer.

Cook says some degree of drought has afflicted the West since 2000. He calls the current 20-year period of dryness a “megadrought,” and says similar conditions haven’t been seen since the medieval period 500 years ago.

“On its own, this drought is a really bad event,” Cook said. “But for a lot of places and a lot of ecosystems, it’s another bad event after a series of bad events that’s likely to result in compounded impacts.”

Those impacts could include species die-offs, altered ecosystems, catastrophic wildfires, economic losses, infrastructure damages, and water shortages.

National parks and more than 100 National Park Service units in the West will not be spared without significant policy interventions.

Even still, America’s contemporary conservation regime — which dates back to the founding of the NPS in 1916 and beyond even to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 — is struggling to protect the nation’s iconic landscapes, plants, and wildlife from the drastic effects of large-scale and long-term climate events such as drought.

The NPS acknowledges it must adapt its stewardship of the parks to meet unprecedented climate challenges ahead. Under the Biden administration, the agency is preparing for a hotter, drier future that it says can affect natural resources and park assets. This is a monumental concession from an agency that just three years ago was directed by former President Donald Trump to dismiss a directive that promoted science-based decision-making as a guiding principle.

Groundwater is the key to life at Organ Pipe National Monument/ National Park Service

Back at our car camping trip in the Stanislaus National Forest, and under the blazing sun, my partner and I pack up the Subaru and drive east on Highway 120 toward Yosemite.

The effects of California’s last multiyear drought and previous fire seasons are ubiquitous.

Leafless gray pine trees, weakened by water scarcity and distressed by bark beetles, share space with charred trees burned by the 2013 Rim Fire, which burned more than 400 square miles in and around Yosemite. At the time it was the largest wildfire ever recorded in the Sierra Nevada.

In 2020, the Creek and North Complex fires were even bigger. Eight of the 10 largest recorded fires in the Sierra have occurred since 2010.

But there are encouraging signs of rejuvenation, too. We see a bald eagle and a peregrine falcon soar overhead. Green saplings rise from the ground. The forest’s rebirth marches to the beat of drumming woodpeckers, which thrive in post-fire environments.

Regrowth is slowly reclaiming the forest burned by the Rim Fire in 2013/Jonathan Horwitz

As we enter Yosemite, we turn left off the highway and begin our snaking descent to the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. More than 100 years ago, John Muir described Hetch Hetchy as a “wonderfully exact counterpart” to Yosemite Valley.

But political and economic pressures mounted to dam and flood Hetch Hetchy to provide water and hydropower to the burgeoning population of San Francisco, a thirsty city desperate after losing most of its water infrastructure in the infamous 1906 earthquake.

“Hetch Hetchy is a grand landscape garden, one of nature's rarest and most precious mountain temples,” wrote John Muir in 1912, before the valley was dammed/Jonathan Horwitz

Today, the eight-mile-long Hetch Hetchy reservoir supplies water and power to 2.4 million Bay Area residents. The story of Hetch Hetchy makes it crystal clear that water in our national parks is as vital to the success of humans and cities as it is to the flourishing of wildlife and natural landscapes.

So long as water scarcity remains a roadblock to urban development in the West, pressure to encroach on nature to tap new water sources, suck up more groundwater, and build more dams will continue to escalate.

“Water is definitely a human need and wildlife needs it, too. It's the one thing we all need,” said Chad Lord, water policy director at the National Parks Conservation Association. “How we address water issues is going to be important in order to better protect not only the natural resources in national parks and park communities, but also the historical and cultural ones.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment