Coral diseases are rampaging through reefs in the Caribbean and Florida.

Coral Disease Represents Ecological Crisis Greater Than 1988 Yellowstone Fires

By Caroline Rogers, Ph.D., U.S. Geological Survey

A disease that threatens an entire ecosystem lies below the surface of the sea – out of sight and out of mind.

The disease, which is rapidly killing corals in Virgin Islands National Park, is a crisis at least on the scale of the 1988 fires that roared across Yellowstone National Park and the continuing infestations of hemlocks and other old growth trees in Blue Ridge Parkway and Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah national parks.

But unlike the forest challenges, this malady is hidden where it can’t always be seen and it is killing corals, which are particularly slow growing; recovery, if it even occurs, can take a particularly long time.

In January, National Parks Traveler called attention to endangered and threatened parks and noted the emergence in 2014 of stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) in Florida and its spread to the Caribbean where it was first observed in 2017.

This deadly disease is still killing over 20 species of corals. Stony coral tissue loss disease is now present in national parks in Florida and the Virgin Islands, including Biscayne National Park, Buck Island Reef National Monument, Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve, Virgin Islands National Park, Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, and found most recently, in May, in Dry Tortugas National Park.

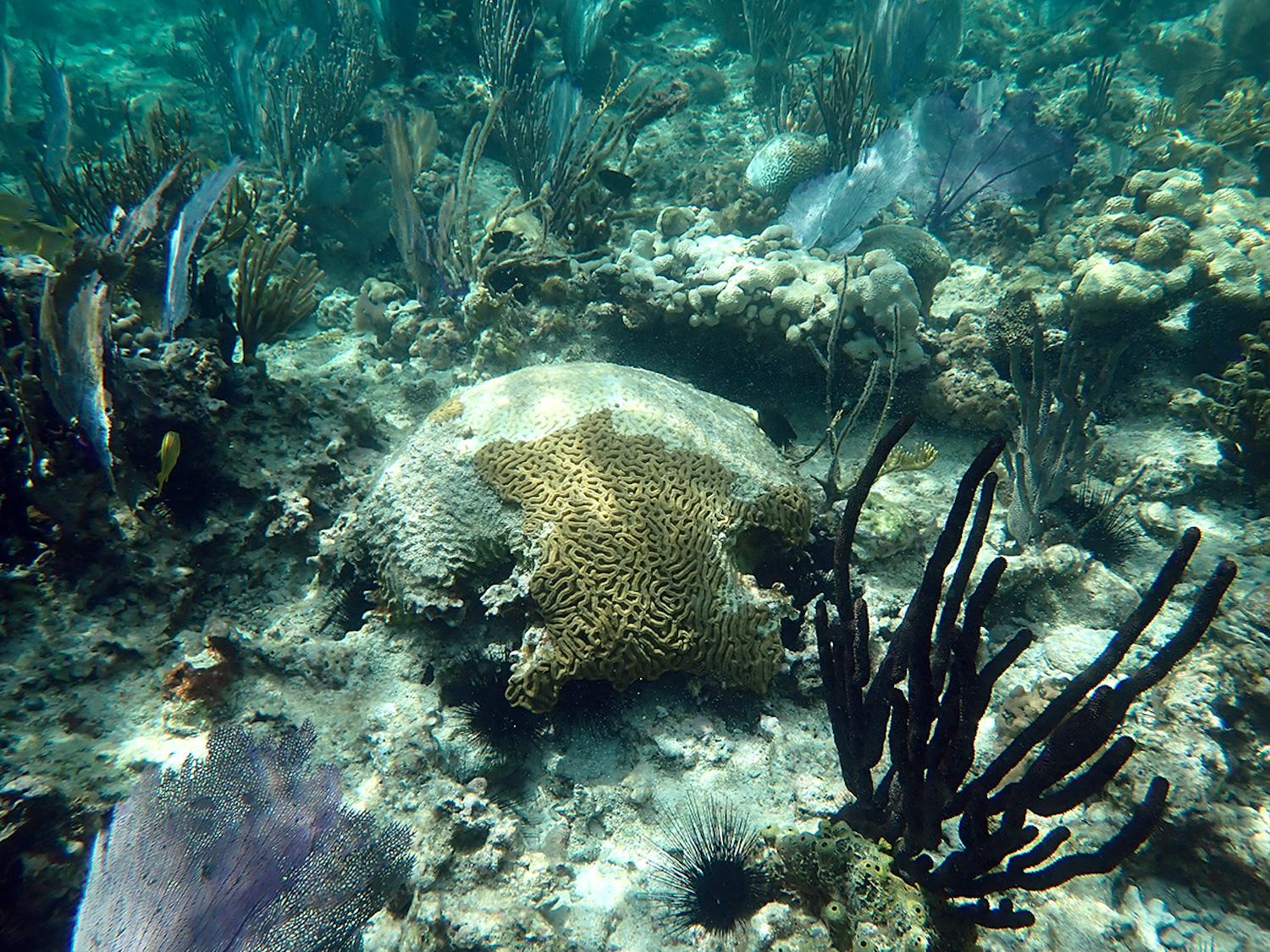

Star Corals and Brain Corals with dead white portions, in Mennebeck Bay, Virgin Islands National Park/NPS, Jeff Miller

In the past, most coral reefs have declined from a combination of injuries from hurricanes, excessive sediments and nutrients, high seawater temperatures, vessel groundings, and other factors leading to a decrease in living coral and an increase in algae.

Many corals in the national parks are still recovering from damage from powerful hurricanes in September 2017. But SCTLD is particularly destructive because it is further reducing already low numbers of coral and has the potential to drive some coral species, including Pillar Coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus), to extirpation.

Corals are architects of the reefs, just as large trees create forest structure. They are solar-powered animals that create a complex physical framework, a rocky structure. In a symbiotic relationship between the corals and the microscopic algae in their tissues, the coral animal receives nutrition from the algae (zooxanthellae), and the algae photosynthesize within the protection of the coral tissues, using carbon dioxide and nutrients from the coral animal. This symbiosis is the basis of all coral reefs as it results in the secretion of limestone rock (calcium carbonate) in a process called calcification.

Coral reefs are not only beautiful, a reason in itself to do all we can to protect them, but also economically valuable. They protect shorelines, including white sand beaches, from erosion during storms and support tourism based on snorkeling and diving. Fish and other reef animals are important as food. And we are just beginning to learn about the numerous drugs that can be derived from reef animals to combat cancer and other diseases.

Sadly, there has been a failure to acknowledge the contributions that reefs make to the well-being of the planet, and reefs around the world have deteriorated, particularly in the last 30 years, from natural and human-related stresses. Warming sea water temperatures that lead to coral bleaching with loss of the zooxanthellae is of the greatest concern. Disease outbreaks, sometimes but not always following coral bleaching, are responsible for the largest declines in coral on western Atlantic and Caribbean reefs.

Here is a closer look at the effects of the disease in Virgin Islands National Park following its appearance in early 2020, and an overview of recent research efforts to learn more about it.

Boulder Brain Coral with active disease, in Leinster Bay, Virgin Islands National Park/C.S. Rogers, US Geological Survey

What does it look like?

When portions of corals die from SCTLD and other diseases, their white limestone skeleton is revealed. The bright white corals are conspicuous and readily visible to anyone snorkeling in Virgin Islands National Park. Maho Bay and Trunk Bay, the park’s two most popular snorkeling sites, currently have some highly visible diseased corals in shallow water. Most of the corals near Waterlemon Cay, another very popular site, have died, including Pillar Corals rising more than 6 feet.

What is happening?

Scientists think that SCTLD is striking at the foundation of all coral reefs---the symbiotic relationship between coral animals and the algae (zooxanthellae) inside their tissues. This relationship drives calcification that results in the physical structure of the reef. Scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey and other agencies have discovered microscopic lesions in diseased corals in Florida that indicate a possible disruption of this fundamental relationship.

More recent investigations of corals with SCTLD by Dr. Thierry Work with the USGS National Wildlife Health Center-Honolulu Field Station using electron microscopy have revealed abnormalities in zooxanthellae associated with virus-like particles, suggesting that SCTLD might be caused by a virus that is killing zooxanthellae, leading to death of coral host cells and subsequent tissue loss. Additional work is ongoing to try to confirm this.

In July, Dr. Work collaborated with National Park Service scientists Jeff Miller and Thomas Kelley to collect samples from diseased and apparently healthy corals in Virgin Islands National Park to help determine if corals affected with SCTLD manifested the same lesions at the grossly visible and microscopic level as in Florida. Corals of 13 species were sampled for examination by microscopy and molecular biology for identification of viruses. Some samples were collected from corals present on long-term monitoring sites maintained by NPS and USGS over the last 30 years, a period for which the park has developed a history of coral diseases.

Brain Boulder Coral with Active Disease in Mary Creek, Virgin Islands National Park/ C.S. Rogers, US Geological Survey

The NPS South Florida and Caribbean Network Inventory & Monitoring Program has documented a decline in coral cover at its long-term sites. Corals covered about 25 percent of the monitored areas 25 years ago, dropped to about 12 percent in 2007, and now scientists are predicting a decline to less than 5 percent as a result of SCTLD. The disease is now widespread in star corals (Orbicella sp.) that represent the largest portion of remaining coral cover on the reefs.

The only direct response attempted to date is treatment of already diseased corals with an antibiotic paste that is not 100 percent effective. Frank Cummings, director of the non-profit Caribbean Oceanic Restoration and Education Foundation, is leading the treatment efforts in the U.S. Virgin Islands along with staff from the University of the Virgin Islands and scientists with the Mote Marine Laboratory.

Many of the marine national parks were designated, at least in part, to protect and conserve the valuable coral reefs within them. Resources are limited for responding to this newest crisis affecting coral reefs. While the waters within Virgin Islands National Park are still clear and beautiful, and the beaches are attracting more visitors than ever before, the extensive loss of the corals could have adverse effects on the entire marine ecosystem, including on colorful fish, octopuses, and sea turtles.

Caroline Rogers is a Marine Ecologist with the Wetland and Aquatic Research Center based at the USGS Caribbean Field Station in St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands. Previously, she was a research biologist with the National Park Service in Virgin Islands National Park (1984 – 1993). She has over 30 years of experience in research on coral reefs and has published papers on coral diseases, the effects of sedimentation, effects of hurricanes, damage from boat anchors, long-term monitoring, reef productivity, coral recruitment, and the threatened coral species Acropora palmata.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment