Traveler Special Report: Invasive Mammals And The National Parks

From hogs to cats to mountain goats, managing non-native mammals, which the public might find cute and endearing, is an ongoing challenge.

By Kim O’Connell

Editor's note: This is the latest installment of an ongoing series on invasive species in the National Park System and the threats they pose.

WHOOSH. It’s a warm, sunny autumn day in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and I’m standing on the side of the main park road. Leaves have just begun turning gold, amber, and red, so the park is crowded with leaf-peepers. A steady stream of cars zooms past. WHOOSH. I try to ignore the traffic and pay attention to what Ryan Williamson, a park wildlife biologist, is showing me: a section of grass along the roadside that’s rutted and rooted up, like someone had gone off-roading with a miniature ATV.

The culprit? Feral hogs. In this case, Williamson believes it was a single feral hog that did the damage in this section along the road, citing reports of a lone pig seen near that stretch in the days before. After a moment, Williamson leads me deeper into the trees to an even larger, muddier area of ground disturbance, this time with wallows of standing water visible. Here is undeniable evidence of the damage that feral hogs do to the park landscape—uprooting native vegetation, creating new wet areas, and competing with native park wildlife for food and shelter.

“They pretty much just run along with their snout and turn the soil over and kind of like clean everything up that's edible,” Williamson says. “They pretty much are in direct competition with all of our native wildlife, so they eat a lot of acorns, a lot of seeds, a lot of nuts, a lot of tubers. All the things that our native wildlife eats, the hog directly competes with them for that.”

Biologist Ryan Williamson baits a feral hog trap at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. / Kim O'Connell

A Systemwide Issue

Feral hogs are just one of several species of invasive mammals that are posing immense challenges to national park managers. Unlike invasive insects or reptiles, invasive mammals are often larger and more “charismatic” animals, difficult for parks to eradicate from a logistical, financial, and emotional perspective. As familiar, furry mammals, these invasives often share appealing traits with iconic park creatures such as bears, bighorn sheep, deer, and wolves. And yet the problems they cause are manifold—damaging and altering ecosystems, competing with or directly preying on native wildlife, or carrying disease.

Invasive or non-native mammals in the national parks include mountain goats at Grand Teton National Park, mongooses at Hawaii Volcanoes, burros at Death Valley National Park, rats on Channel Islands, and cattle in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Feral hogs (also called swine or pigs) can be found in parks from coast to coast, from the Smokies, Cumberland Island National Seashore, and Congaree National Park in the Southeast, to Big Thicket National Preserve in Texas and to Pinnacles National Park in the West, among others.

According to a 2018 National Park Service report Biodiversity Under Siege, Invasive Animals and the National Park Service, more than half of all national parks contain invasive animal species, including mammals, and only a small percentage of these animals are considered to be suppressed, contained, or eradicated. In 2016, NPS counted 37 invasive mammal species in the National Park System, spread across every region and representing nearly 350 known populations. The report noted that, “When charismatic species are involved (e.g., mountain goats, feral cats, feral horses) or visitor experiences are impacted (including public health or safety issues) there is more interest and pressure from the public regarding how they will be managed.”

Methods to control invasive mammals vary widely from place to place, depending on the dynamics and biology of the particular species, funding, resources, and public opinion—but usually include some combination of hunting, fencing, neutering, and relocation.

"Feral swine are one of the biggest issues in the parks," says Jennifer Sieracki, the NPS national invasive species coordinator. "Many impacted parks have trapping programs to control this species. Free-ranging cats also cause problems in dozens of parks. They are efficient hunters, and also bring disease concerns with them. They can be very difficult to manage, so we ask people to help us by keeping their cats indoors, surrendering them to a shelter if they can no longer care for them instead of abandoning them outdoors, and refrain from feeding outdoor cats."

Sieracki adds that feral horses and burros occur in fewer parks and tend to be managed by individual parks as needed. "Parks generally work with partners to round up and remove animals from the parks that then adopt them out," she says, "and may also construct exclosures around sensitive spring areas to protect them from grazing and trampling."

Even if a park successfully eradicates an invasive species, however—and that’s a big “if” in most places—constant vigilance is required. And for an agency whose maintenance backlog was last known to be about $12 billion, constant vigilance often remains too expensive to do.

Hog Management

At Great Smoky Mountains, the park has accepted that some resident population of feral hogs will likely persist well into the foreseeable future, Williamson tells me, mostly because the park just doesn’t have the staff numbers or funding to mount a complete eradication program for the 1,500 or so swine thought to live within park boundaries. What this means is yearly culling efforts to keep the current population under control and gather tissue samples for ongoing scientific research.

Biologist Ryan Williamson checks a motion-sensing camera near a feral hog wallow at Great Smoky Mountains. / Kim O'Connell

The park’s feral hog population dates to about 1912, when wild boars were brought in from Russia to a private (and presumably fenced) hunting preserve just south of the present-day national park, Williamson says. At some point, pigs escaped and commingled with domestic pigs on local farmland, establishing a crossbred population with both Russian and domestic genetics whose descendants roam the park to this day. The national park has been trapping and shooting invasive feral hogs for decades, having removed an estimated 13,000 individuals to date. Now, the park eradicates about 250 to 300 hogs every year.

But several factors make management difficult: First, most of the more than 800-square-mile park is forested backcountry. In the summer, feral hogs tend to seek higher ground where the temperatures are cooler but are harder for park biologists to reach, so most culling takes place in the fall and winter, when hogs are foraging at lower elevations that are closer to park roads and access points.

Hogs are also seen as valuable creatures by hunters and other stakeholders, says Dr. Becky Epanchin-Niell, a senior fellow at Resources For the Future, a nonprofit think tank, who conducts research into various invasive species issues.

“The fact that some people strongly value their presence on the landscape can hinder control programs," Epanchin-Niell says, "because people can maintain populations on their land that can serve as sources to other locations on the landscape, making it harder to prevent damages elsewhere. Even more challenging is when some people might even purposefully introduce the species to new locations to establish new populations for hunting.”

Another issue is the pig’s prolific reproductive cycle. “A group of pigs is known as a sounder, and typically in a sounder it's pretty much a matriarchal group,” Williamson says. “It's a bunch of females with young and then you'll have occasional boar show up. They have an incredible gestation period. It's three months, three weeks, and three days. So if you have an adult hog who goes through a pregnancy and then has a litter, she could have up to three litters in a year. It's usually somewhere between eight to 12 pigs in a litter; sometimes we see four to six. Plus once she has that litter, there's potential that that litter can start breeding at six months old. So it's kind of an exponential growth curve if left unregulated.”

Williamson and I soon trek to a different section of the park where several hogs have been known to be wallowing. Here a large, low-lying section of earth is completely turned over and rutted, with deep holes full of standing water.

“They’re very destructive on a lot of plant species, especially endangered plant species, because of wet spots or seeps," the biologist says. "That's the most limited ecosystem we have here in the park, because we're in the mountains. So finding wetlands is pretty rare here. Our pigs are really focused on those spots because it's easy to tear up and they can turn that soil over and grab those tubers and roots. They really key in on those areas, which is destructive for those wetland species of animals.”

Williamson points out a camouflaged camera mounted to a nearby tree. He and his colleagues have posted several such cameras in strategic areas of the park where they think hogs have been, as a means to collect data on the animals’ movements but also so they can spring remote-operated trap doors to capture hogs for eradication. Williamson takes me to a single box-style trap that would catch one hog at a time. After sprinkling some corn kernels inside the trap and covering the floor of the trap with dirt, he triggers the trap door to close. SLAM! The sound echoes off the nearby trees.

Culling and Capture

Other national parks have their own systems in place to deal with invasive mammals, which often involves coordinating with other land management agencies, law enforcement, nonprofit groups, and private citizens. At the Smokies, for example, the park partners with the USDA's Wildlife Services branch to do scientific research to discern whether any disease is present. Feral hogs are associated with pseudorabies, which doesn’t infect humans but can affect other animals such as domestic hogs and other livestock, and swine brucellosis, which humans can contract.

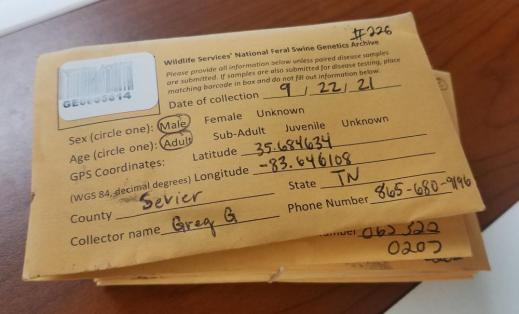

Feral hog tissue samples at Great Smoky Mountains. / Kim O'Connell

“We try to partner on any kind of disease monitoring and anything [similar] that anybody’s willing to participate in with us,” Bill Stiver, the supervisory biologist at Great Smoky Mountains, tells me, as a stack of small manila envelopes stuffed with hog tissue samples sits piled on his desk. “We're also a partner in WHEAT, the Wild Hog Eradication Action Team.” This is a multi-agency partnership that’s mostly focused on Tennessee parks, public lands, and communities.

Similar work is happening elsewhere. At Glen Canyon, for example, the park is working with the Bureau of Land Management and local officials to remove up to 50 non-native maverick cattle from the canyons of the Escalante River via a round-up, with the idea that the animals could be brought to market and sold.

At Pu‘uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, this summer NPS and other agencies successfully removed 458 invasive goats, using directive fencing to corral the animals into a certain area where they were allowed to be distributed to interested parties and taken elsewhere.

At Cape Hatteras National Seashore in North Carolina, an estimated 3,000 feral cats are roaming Hatteras Island, of which about two-thirds is federally managed, and pose threats to nesting shorebirds and other native animals. According to Debbie Martin, founder of the nonprofit Friends of Felines-Cape Hatteras Island, tourists feeding cats is an ongoing problem at the seashore. Whereas a tourist in Yellowstone might know better than to feed a grizzly bear (one would hope), feral cats look like household pets and are irresistable to some park visitors. Although not an official partner of the park, Friends of Felines–Cape Hatteras Island runs a trap-neuter-return program that helps to hold down cat populations in a way that Martin says is humane and is a counterpart to NPS's culling measures.

And at Grand Teton National Park, park officials are continuing a qualified volunteer culling program to help eradicate non-native mountain goats, which threaten the park’s single native bighorn sheep population, considered vulnerable in the Teton Range.

An image of a hog in a corral trap, captured via a remote mounted camera in Great Smoky Mountains. / Ryan Williamson

In December 2019, a panel of park researchers published a study in Biological Invasions that examined the invasive species issue in the national parks. Among other findings, the panel determined that coordinated action will be required to adequately deal with invasive species, and acknowledged that a lack of leadership was likely an inhibiting factor to moving forward (although Dr. Ashley Dayer, the lead author of the study, notes that NPS has since taken the step of naming Sieracki as a national invasive animal coordinator). The recent confirmation of NPS Director Charles "Chuck" Sams could also move the needle on invasive species projects, with perhaps more partnerships and public engagement on the issue—both cited as necessary in the study—as well.

"Parks will work together to develop tools to help them manage invasive animals, but for the most part parks find great success working with partners at the local level on cross-boundary invasive species issues," Sieracki says. "At the national level, we are working to set up partnerships that can be implemented at the local level with park staff. We also frequently collaborate with other federal agencies to tackle issues at a national scale by identifying priorities, developing policies, generating innovative tools, and sharing information."

When resources are spread thin, having efficient technology is paramount. “We wear many hats,” Ryan Williamson says. “It almost gets to the point to where you can do a lot of things well, but when you can't focus on one thing with so much going on, that can inhibit what we can get done. If I had a group of 25 pigs on bait and I had a bear issue, I’d have to go deal with the bear issue.”

In a quiet section of the park, Williamson shows me a corral-style hog trap, which is designed to sit in the landscape for some time, allowing groups of pigs to become accustomed to it. Once a group wanders in, a motion-detecting camera will transmit images via cell-phone app, allowing park biologists to spring the trap door remotely. One time, the park caught nearly two dozen pigs at once using this kind of trap. Large netting traps can also catch many pigs at once too, although they are harder to install in a heavily forested setting.

Once the pigs are killed, the park allows the carcasses to remain on the land for scavengers. In this richly biodiverse landscape, the natural recycling of a 200-pound pig carcass can be the work of just a few hours.

“The circle of life in the park,” Williamson says, “is very short.”

Previous installments in this series:

Traveler Special Report: The Invasion Of The National Park System

Traveler Special Report: Invasive Fish in National Parks

Audio Postcard From The Parks | Battling Russian Olive At Glen Canyon NRA

Traveler Special Report: Vegetative Invaders In The National Parks

Charitable Dollars Help In Fight Against Invasives In National Park System

Traveler Special Report: The Cost Of Invasive Species In The National Park System

Traveler Special Report: Battling Invaders With Fire At National Battlefields

Traveler Special Report: Measuring Successes Against Invasive Species

Traveler's Audio Postcards From The Parks: Hog Wild

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment