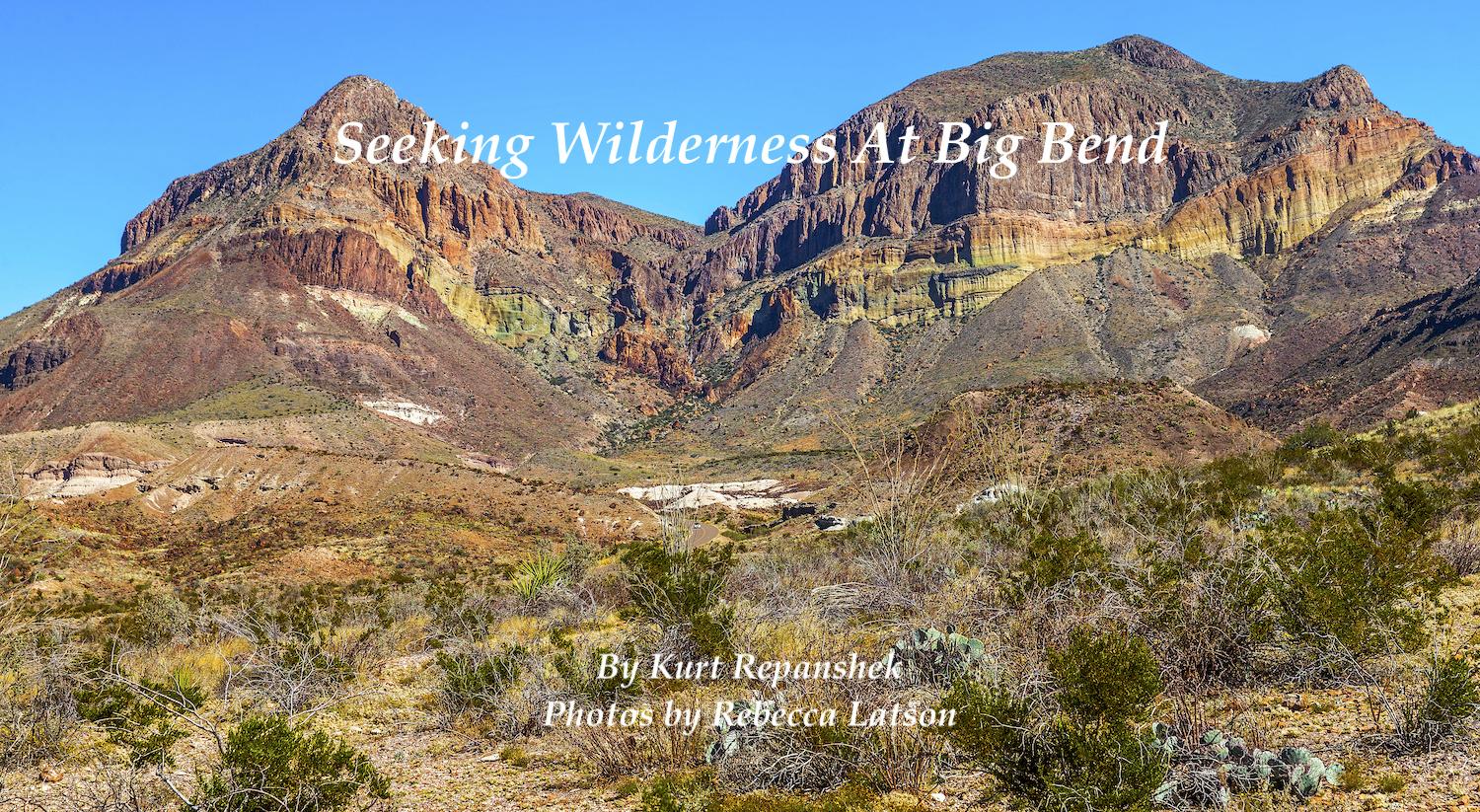

A grassroots effort is under way to see official wilderness designated at Big Bend National Park/Rebecca Latson photo of Goat Mountain

Big Bend National Park draws its name from a hard curve in the Rio Grande River that separates this part of Texas from Mexico, though the rugged Chisos Mountains that lie completely within the park's boundaries could just as easily have lent their name to this geograpically and geologically complex landscape.

Sprawled across more than 800,000 acres, Big Bend ranges in elevation from 1,715 feet above sea level along that iconic river to nearly 8,000 feet along the roof of the Chisos range. Weeks could be spent exploring this raw landscape to develop a general understanding and appreciation of its geologic faults and volcanic underpinnings, its palentological resources, its robust avian inventory of more than 450 species, and its cultural history that stretches back roughly 10,000 years to when Paleo-Indians made their life on this land.

All the while during that exploration, the Chisos Mountains would be in sight. Also in sight, though with invisible borders, are nearly 600,000 acres of the park that have been identified as holding wilderness qualities: untrammeled forests and mountains, places that retain their primeval character and influence and which are essentially without permanent improvement or modern human occupation.

More than four decades ago, in 1978, the National Park Service reported to Congress on the wilderness qualities of 583,000 acres of Big Bend. It was a report that recommended those acres for official wilderness designation, but also a report that evidently was shelved, as Congress never considered legislation to add those 583,000 acres to the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Across the roughly 85-million-acre National Park System there are some 70 million acres envisioned as wilderness. Forty-four million acres have received official Congressional blessing as such, while another 26 million acres are in something akin to administrative limbo. Some of those 26 million acres -- including 2 million in Yellowstone, more than 1 million in Glacier, and at least 583,000 in Big Bend -- have been recommended for official wilderness designation and seen those recommendations languish.

The concept of approving lands for their wilderness qualities dates to 1964, when President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed The Wilderness Act into law.

"If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology," President Johnson said at the time. "We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it."

Since then, nearly six decades ago, less than 2 percent of the lower 48 states have gained protection for wilderness, according to The Wilderness Society. It's a slight that President Johnson would be disappointed to learn.

While the National Park Service is in the preservation business, as laid out in the National Park Service Organic Act, there are surprising gaps of official wilderness in the park system. Fifty-eight years after The Wilderness Act was signed by Johnson, not a single acre of Glacier, Yellowstone, Great Smoky Mountains, Canyonlands, Arches, or Big Bend are protected as official wilderness.

Keep Big Bend Wild

Today, a grassroots group at Big Bend hopes to convince Congress that now is the time to correct that oversight and protect most of the park as official wilderness. The group, Keep Big Bend Wild, is not seeking to expand wilderness designation to lands in the park currently open to facilities and roads, but rather to "preserve in perpetuity the wild nature of Big Bend National Park in its currently undeveloped areas for the public benefit and the benefit of natural communities. To maintain appropriate visitor amenities and administrative support facilities in currently developed areas of Big Bend National Park and focus the development of any needed future infrastructure there or in neighboring communities."

Casa Grande rises up out of a wilderness study area in Big Bend/Rebecca Latson

Raymond Skiles, who served as the national park’s wildlife and wilderness coordinator before retiring, is one of Keep Big Bend Wild's core team of drivers. Gaining official wilderness designation, he said last week during a National Parks Traveler roundtable discussion along with Big Bend Superintendent Bob Krumenaker and local writer Ben English, would protect a rugged and unique landscape.

"It's the prime example of protected Chihuahuan desert landscape," Skiles pointed out. "The Chihuahuan Desert being just a portion of our Southwestern U.S., mainly limited to parts of New Mexico and in Texas. But it is a rugged and arid landscape. It's got mountains, the Rio Grande River abuts an extensive portion of it. In fact, the entire border of Big Bend National Park is along that river and then just, you know, the open desert that has been protected for all this time since 1944 with very little development in it.

"It's classic qualification for wilderness is that there's lots of opportunity for wild recreation, for solitude, for also seeing a historic and prehistoric evidence that remains on the land which is included in wilderness values," he added. "And you know, certainly, if someone wants to spend a week or more out with relative solitude and a wild landscape, it's hard to think of a place at least on the lower 48 that would qualify more than Big Bend would."

Despite its arid reputation, this landscape holds botantical wonders in the form of the spindly stalks of ocotillo that erupt in red blooms, a handful of yucca varieties, several types of orchids, various members of the aster family, a kaleidoscope of other wildflowers and, of course, more than a few species of cacti, including hedgehog varietals, prickly pear, Christmas cactus, and the uniquely named, and similarly shaped, pingpong ball cactus.

Big Bend also is home to pronghorn antelope, elk, black bear, mountain lions, four types of skunk, pecarries, badgers, ringtails, numerous bats, rats and mice.

Nurturing The Human Condition

That wilderness exists is central to the human condition. We need a place in nature where we can retreat and come not just to terms with the natural world, but to interact with it and learn from it. We need places where we can renew our connections with the beauty of unbroken forests, gin-clear streams dancing down mountainsides, remote lakes, and endless tundra. Being able to experience the goose bumps that rise on the back of our necks at the sound of a howling wolf or the sight of a grizzly also are a necessary part of untamed wilderness.

In January 2021, Bradley Allf, a PhD student at North Carolina State University studying conservation biology and public engagement in science, wrote about that needed human connection.

Humans have always had a connection to the wild: to undomesticated vistas and natural landscapes. That connection forms an important aspect of human culture, our collective imagination, and our self-conception, even as specific feelings about the wild have changed over time. -- Bradley Allf.

English, an eighth-generation Texan who grew up in the Big Bend area, couldn't agree more with Allf.

"I think that's one of the problems we have in our society at this point, is so many people are removed from where they came from," he said. "You need wilderness. You need wide open country. You need to get back away from all the technology that surrounds us each and every day, and really experience the simple, yet most important things, in this world. And that comes many times from being in the wilderness or just out by yourself someplace."

Signs that volcanics were part of the park's geologic history can be seen in parts of the WSAs/Rebecca Latson

Having lived the majority of his life in the Big Bend region of West Texas, English has had ample opportunity to venture into the park's potential wilderness. It's a landscape his family has deep ties with.

"My family's been in that country since the 1880s," he said. "When I go out there, I feel them with me again. You talk about knowledge of the country, knowledge of the area and such, and people said I know a little bit about that country. I write about it. I spent a lot of time in it. But they had more knowledge in their little bitty finger than I got in my entire body. They had to because they live there in very primitive situations even up through the 1960s and such. No electricity, no TV, no radio, nothing like that. And when I get out there, I'm connected to them again. It's something that's hard to describe in mere words. And it's not only them, but the kin that they had and the friends they had. People I heard about my entire life. Still learning about. I'm trying to cover that country now for nearly 60 years. I'll never see it all, but that won't keep me from trying."

The Preservation Business

Official wilderness designation removes the risk that Big Bend's wild and rugged landscape will be altered sometime in the future. It has been managed as wilderness, but that doesn't mean Congress down the road might not decide Big Bend needs more lodging or road access and looks to the WSA lands as possible locations.

"Policies do change, elected officials change, superintendents change, and yet, every time we survey the public, formally or informally, what they tell us is what they love in this place, and it's probably true at Yellowstone, too, is the mix of those wild places that Ben and Raymond so eloquently described, and the fact that they can drive here, stay in a campground, stay in a hotel, eat a meal in a restaurant," explained Krumenaker. "We're looking at trying to definitely manage that combination of things in the future. And, you know, the park's been here a long time, much of the infrastructure was built in the 1950s and '60s, and the visitation to this park is increased by a factor of five or six since that time.

"In fact, in the last year we were 25 percent higher than any year in our in our past history. So there's going to be more and more people coming to Big Bend," he went on. "And there's probably going to be more and more pressures to accommodate them. And some people will think the best way of doing that is to build more lodges, more developed campgrounds, more roads, and you know, an argument can be made for that. But at the same time, we run the risk of destroying the very most important values that people come here for, which are so lacking in the United States, and especially in the state of Texas, which is that open space that Ben so beautifully described."

Through official wilderness designation, those values and resources can be "protected forever," said the superintendent.

What Needs Protection

English doesn't quite know where to start, or to finish, when asked how best to explore and enjoy those 583,000 acres of potential wilderness.

"There's no one best place. It just kind of depends on what your mood is," he replied. "Now, there are some special places I like to go to that are kind of remote. The Sierra de la Punta. The area around Mule Ears. It's so rough most people won't go into that country. And out towards Smoky Creek, and up Smoky Creek to the Sierra Quemada. But you can go across the park, go into the Dead Horse Mountains. You want someplace that hardly anybody goes, it's to Dead Horse.

He also pointed to a section of Big Bend that was added to the park in 1987 through a 67,125-acre donation from Houston Harte, who gave over his ranch to the park that year.

"Time stopped in 1987 there. Nobody goes into there. And you can go up from the Houston Harte area -- it's not very wide, but it's long -- you end up almost all the way to Cedar Spring, behind Nine Point Mesa," said English. "I guess what I'm saying is, you can put the Big Bend National Park up on a map, take a dart and just throw it, and wherever that dart hits, there's something to be seen there."

How this landscape could, or might, contribute to a National Biodiversity Strategy that has been discussed by some, or in helping slow the sixth mass extinction or contribute to the Biden administration's goal of preserving 30 percent of the nation's lands and waters for nature by 2030 remains to be seen. Nevertheless, wilderness designation benefits conservation.

The Mules Ears section of backcountry in Big Bend is a rewarding destination for those seeking wilderness attributes in the park/NPS

"I think the answer is protecting lands as wilderness in Big Bend National Park is certainly good for conservation," answered Krumenaker when asked how wilderness designation would fit into those initiatives. "And any politician that wants to support conservation, it would probably support that person's goals. I think the key though, you know, wilderness is a political issue, and most wilderness initiatives that you mentioned earlier that have gone nowhere have gone nowhere not because the lands don't have value, but because there wasn't the political support from it from the voters of the politicians' districts.

"One of the key things we're trying to do here is not start by suggesting that anybody write to Congress and protect Big Bend as wilderness, and not to link it to any particular administration's initiatives. But to do as Ben was saying, just have people reconnect to what's so important here," he went on. "We want to have people who care about wild places, who care about the future, who care about their grandchildren, who care about the human connection to the land. Understand that regardless of their politics, there's something here at Big Bend that is worthy of their support and protection."

The value and protection of wilderness, said Skiles, also provides some economic certainty to the park's surrounding communities.

"Quite often, and it certainly was the case in 1978, that the local concern can often be driven by what I consider the misperception that it could be something detrimental to the local economy, and certainly, Big Bend is a driver really in several counties' economies. Immediately, Brewster County, you know, tourism is the, if not one of the major, income streams," he said. "It's just quite obvious if you spend much time around national parks or wilderness areas; they're big attractions. People have determined that they want to be near these protected areas, for that ability to have the pristine view from their house if it's outside of the park or wilderness area. But more so just readily accessible open landscapes, trails for hiking, camping, birding, or the ability to go horseback or just toughing it out across no trails wilderness, which is a great opportunity in Big Ben.

"So, it's a little bit ironic that while we are protecting from development, and some could say, well, that could be poor for the economy, it actually is the goose that lays the golden egg in many ways for tourism economy," said Skiles.

Where the initiative goes remains to be seen. While those behind Keep Big Bend Wild hope to see official wilderness designation bestowed by Congress by the end of this year, so far none of Texas' congressional delegation has been on the ground in the park to discuss the initiative, although U.S. Rep. Tony Gonzales has been briefed on the effort.

"This is not about changing the use," Krumenaker stressed. "It's not about restricting use any more than it is right now. It's about assuring that the mix of uses that we have today are the same ones that we will have in the same places for future generations. And I think people are reassured when they when they get past the rhetoric and they understand this is about preserving what they've already told us they love so much about the park."

Listen to the podcast: Seeking Official Big Bend Wilderness

Follow writer Bob Pahre on a trek into Big Bend's backcountry wilderness.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Great article.

I think you capured the essence of BBNP and how to enjoy it.