TWENTYNINE PALMS, CA –- On a recent morning, I waited more than 20 minutes to enter Joshua Tree National Park, behind a line of vehicles spewing pollution into the air from their tailpipes. Those emissions contribute directly to climate change, our parks’ most existential threat. Reducing those emissions, via a major and rapid shift to electric vehicles, is one of our best hopes at avoiding the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

But the National Park Service itself acknowledges it doesn’t currently have the infrastructure to handle a major transition to EVs. Fixing that won’t be easy.

President Biden has set an ambitious goal of constructing 500,000 individual chargers across the country by 2030. Importantly, a major focus of the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program (NEVI) is to strategically locate charging stations along “designed Alternative Fuel Corridors, particularly along the Interstate Highway System,” a Federal Highway Administration spokesperson said in a statement to the Traveler. The program is just getting off the ground, though, and it’s too early to tell how successful it will be.

For the sake of the parks, it needs to be successful.

“One of our biggest challenges comes with infrastructure in the park for charging stations,” Joshua Tree Superintendent David Smith explained to the Traveler from his office at park headquarters. “It’s no problem to come up from Palm Springs for the day” –- he pointed to the map on his wall -– but visitors need to make sure they start with a full charge if they are coming from the more remote side of the park.

Ashley McEvoy, senior manager of resilience and sustainability at the National Park Foundation expanded on what makes building charging infrastructure at parks so complicated: “The biggest challenges relate to what makes national parks so special in the first place -– how different they can be. Each park has its own specific needs, and … many parks are in remote locations and power supply can be a challenge.”

Harnessing the power of the sun into electric vehicles at Joshua Tree could be challenging/Sarah Guzick

Reducing emissions from visitors is, of course, the biggest benefit of EVs. But park operations also matter, and EVs pose a different set of challenges on that front.

Joshua Tree currently has about 62 “fleet vehicles,” only one of which is electric. But, the park has a goal to “convert every vehicle we can” to electric by 2030, said Smith. “We can” is an important caveat -– the technology just isn’t there yet for electric vehicles to do everything the park could need, particularly around emergency response.

“It’s mostly a range thing and a little bit of a 4-wheel-drive and clearance thing. The vehicles that are out there right now don’t seem to have that, which we really need in some of these sandy areas,” explained Eric Linaris, Joshua Tree’s chief ranger.

So, electric vehicles offer a huge amount of promise for parks but, like for the rest of the country, the gap between reality and potential is Grand Canyon size. What should the Park Service -– what can the Park Service do -– to help accelerate the electric vehicle transition.

Sitting in his office, Smith laid out how he sees it for Joshua Tree. “We are not the 3.1 million people who visit every year,” he said. “We’re a staff of about 120,” and that’s all they have the capacity to handle. Joshua Tree’s role, the superintendent continued, is to “set the tone” for the public.

“We have the capacity to be net-zero” in the next couple of years and that’s an important example for the public, said Smith. “They know we’re trying to walk-the-talk.”

Solar panels on top of Joshua Tree headquarters/Michael Sparks

To understand the issues other parks are grappling with when it comes to EVs, the Traveler reached out to Shawn Norton, the Park Service’s lead program manager for sustainable operations. Norton did not respond, though, and the Park Service’s public affairs staff said, without directly addressing the question in any detail, that the agency “recognizes the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and strives to utilize efficient and alternative transportation operations in as many parks as possible.”

Adapting all 423 national park units for an EV world is no doubt a major challenge. However, according to internal documents obtained by the Traveler, the Park Service is moving to assemble a task force to “oversee the service-wide electrification of our fleet.” While clearly still early -- one question outlined is whether the Park Service should lease “a majority of the fleet” to allow for easier vehicle upgrades as EV technology improves –- the documents point to funding as a major hurdle parks must overcome.

But there are many other issues. What resource and regulatory hurdles (e.g., archaeological or environmental) would have to be cleared to bring in the power needed to support chargers? Is the needed power available through gateway communities? Will individual parks be responsible for contracting for chargers, or will a national contract be engineered by the Park Service? Where will the funding come from to pay for not just the installations, but the replacement of park fleets with EVs? Should the Park Service concentrate initially on installing EV chargers before replacing its fleets?

Diego Lopez, executive director of Northern Colorado Clean Cities (NCCC), said his group has been working with Rocky Mountain National Park for years to install charging stations in and around the park, as well as providing the park with electric fleet vehicles. Still, the park only has a handful of charging stations because of its remoteness and the fact that the “cost of electricity in rural areas is higher than urban areas,” Lopez said, as is the “cost to transport the materials” for station construction. One way NCCC has been working around this problem is by helping gateway communities, like Estes Park, Colorado, build out more of its EV infrastructure.

Though in its infancy, California’s Pacific Gas & Electric’s “Community Microgrid Enablement Program” has the potential to be useful for parks. Microgrids are self-sustaining power grids that run on renewable energy, like solar. They can be built almost anywhere and have the added benefit of allowing the utility to avoid costly and dangerous overhead power lines which, especially in California, have caused tremendously destructive wildfires.

The idea of independent microgrids seems to fit perfectly with the Park Service’s needs, especially at a remote location such as Joshua Tree. Why not use already disturbed land -- like parking lots -–and build sun shades (as solar panels on parking lots are often called) that act as EV chargers?

Ken Gillingham, professor of Environmental & Energy Economics at the Yale School of the Environment, says the idea could work in some parks, but not everywhere. “I think that approach would be expensive relative to just bringing out more capacity and further lines (at least at today’s costs), but very possible, at least for some parks.”

Joshua Tree recently acquired several hundred solar panels and “I’ve challenged our building foreman to look at our parking lots and see if shade structures are feasible and if that’s something we can support,” Smith said. “You get the benefit of cooling off cars and using an already disturbed area.”

The challenge of using many small distributed areas like parking lots is that “power is designed to flow from big power plants down to our houses,” as Destinie Nock, assistant professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon, explained to CNBC last January. “That one way direction has really limited our transition to more renewables and their storage.”

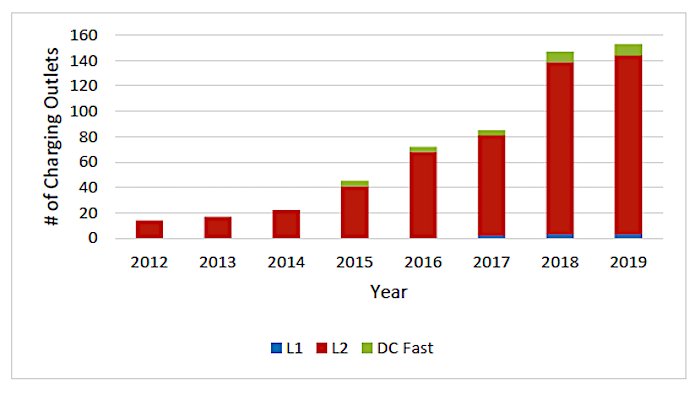

Since 2010, the NPS has worked to offer electric vehicle charging as an amenity for park visitors. These efforts have been achieved through partnerships with entities such as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office, BMW, and the California Energy Commission. The chart above illustrates the increase in public and private (i.e., workplace and fleet) charging availability in National Parks between 2012 and 2019.--NPS

Because of that limitation, it may be the case that one of the best ways to save Joshua Tree National Park is to kill Joshua trees, depending on who you ask. A fight has been brewing for years just outside the boundaries of the park as developers seek to build massive solar farms that can generate enough power for entire cities. But doing so requires, euphemistically, “displacing” the iconic trees and disrupting the desert ecosystem.

In fact, the Biden administration just approved two massive solar projects on U.S. Bureau of Land Management land in Riverside County nearby Joshua Tree. And a few years ago a major dispute played out over the Palen Solar Project, which would power nearly 20,000 homes but also displace Joshua trees and endanger many of the plants and animals that live in the Mojave Desert.

At the time, Brendan Cummings, conservation director for the Center for Biological Diversity, told the L.A. Times that “If you have to mow down hundreds, perhaps thousands, of climate-threatened trees, and disturb carbon-sequestering soils, to build your climate-friendly project, that’s a pretty good indication you’ve put it in the wrong place.”

"The desert is now plowed up, and the habitats have been destroyed, the ecosystems have been destroyed," Patricia Robles, chair of the Lacuna de Aztlan Sacred Sites Protection Circle, a Native American group, argued during a hearing at Palm Springs City Hall in 2016. "The desert bioregion is a very important region to the world and it is very hard to restore. You will never see the desert the way it was prior to the destruction."

But given the existential scale of the climate crisis, others urge speed, even if that means surrendering part of the desert. “We’ll Have to Sacrifice Joshua Trees to Save Them” was the headline of an October essay in the L.A. Times, written by two biologists and an ecologist.

The Department of Energy, for its part, recommends erecting solar panels in both cities and rural areas.

Capturing solar power long has been done by the Xanterra Travel Collection at its private inholding at Death Valley National Park/Kurt Repanshek file

Asked if the desert habitat of Joshua trees was an appropriate place to build massive solar farms, Smith offered a nuanced take: “Anything we can do to reduce the amount of carbon emitted, we’re generally supportive of, but we also acknowledge there’s an appropriate place for energy development and there are some places that are inappropriate.”

Such as?

“Inside of a national park. To create a large solar array in a place that is so meaningful to the American public is not appropriate … but given how big California is and our demand for energy, there are places that are appropriate.”

There is no obviously correct answer for how to support EVs in parks. The climate crisis is a complex problem that requires complex solutions. As Smith, who drives a Tesla himself, mused, “These are some super big challenges. Given the prospect of climate change destroying Joshua Tree and other national parks, land managers and all of us are going to have to decide: there are going to be some sacrifices, is this an appropriate sacrifice?”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

"given the existential scale of the climate crisis". My goodness. It's a thing, but let's stop acting as if the sky is falling next week. Let's stop acting as if the mostly fossil-fuel based generation of electricity and those unrecyclable car batteries is net zero.

E-cars in remote, fragile parks is like a square peg in a round hole. It will be decades before the technology can handle the needs of police, fire and EMS vehicles which must be able to run continuously for hours; sometimes days. I'm not sure Elon Musk has even envisioned a battery that can power a fire engine w/ all its pumps for 8 hours. You want someone rescuing you in a remote part of a park to be worrying about running out of car battery?

You're actually dicsussing cutting down trees in or around a park to build solar panels? Let's come up with cures that don't kill the patient.

Has the conversation moved from e-buses and shuttle systems to building "green" infrastructure in/around the parks?

Look wider. Electric technology belongs in tightly packed cities first, where it's economical and advantageous. Fix LA and the relatively minisule numbers of park visitors in SUVs become statistically irrelevant.

This isn't a solution but would be nice if there was some way to shorten the line getting into parks. Have one entrance lane for those with passes so we don't have to sit in a line that seems to take forever while our cars are running. I don't know if the majority in line have passes and would like to get a map and drive on? Anyway, I would like to see a faster way to get into parks. One time getting into Arches was an incredibly long wait (I can't really remember how long of a wait it was but I know it was more than 20 minutes!) And, it was the off season. Just a comment I've wanted to make concerning many national parks.

The EV are good for the environment but they don't pay road usage taxes, that occurs when we buy fuel, this needs to be addressed as well!

Having worked in parks for almost 40 years I can confidently say at least half of the current fleet of vehicles could transtition to fully electric within the next decade. Many park vehicles are driven less than 100 miles per day and could easily be fully charged overnight with a level 2 (240 volt outlet) charger. In the past the constraint was primarily the availability of utility vehicles like pickup trucks but that is changing rapidly. Options for plug-in hybird vehicles are also much more common. There will need to be funding to install relatively inexpensive level 2 charging stations for park vehicles. The much more expensive direct current fast charging stations are usually not needed. Initial costs for EVs are still higher than most gas powered vehicles but the operating costs are far less.

P.S. I think the road use tax for EVs can at least partly be addressed by entacting a tax at DC fast chargers which is the equvilant of a gas tax at the pump. This won't cover home charging, where most EV owner charge most of the time, but it is a start.

This article is undated but based on the comments it appears to be from early 2022. The EV charging situation in our National Parks doesn't seem to have improved much since. I tried to plan an EV drive to Sequoia NP but this proved to be impractical due to the complete absense of destination charging at the park's lodges or anywhere else in the park. Meanwhile, Yosemite has four charging stations and the Bay Area parks all have them even though they are near urban areas with plentiful charging opportunties. Contrary to what is said here, installing destination chargers (L2) is not expensive, we're talking ordinary 240v wiring at 50a. Even 30a would be useful for overnight charging. It just isn't being done in many parks, and the reason why is unclear. Is it up to the franchees of the park factilities or the NPS? So ironically we're driving our gas burner into Sequoia, but not by preference.