Climate projections under current warming trends across the globe point to significant changes across the National Park System, according to an analysis prepared by the researchers at Climate Central.

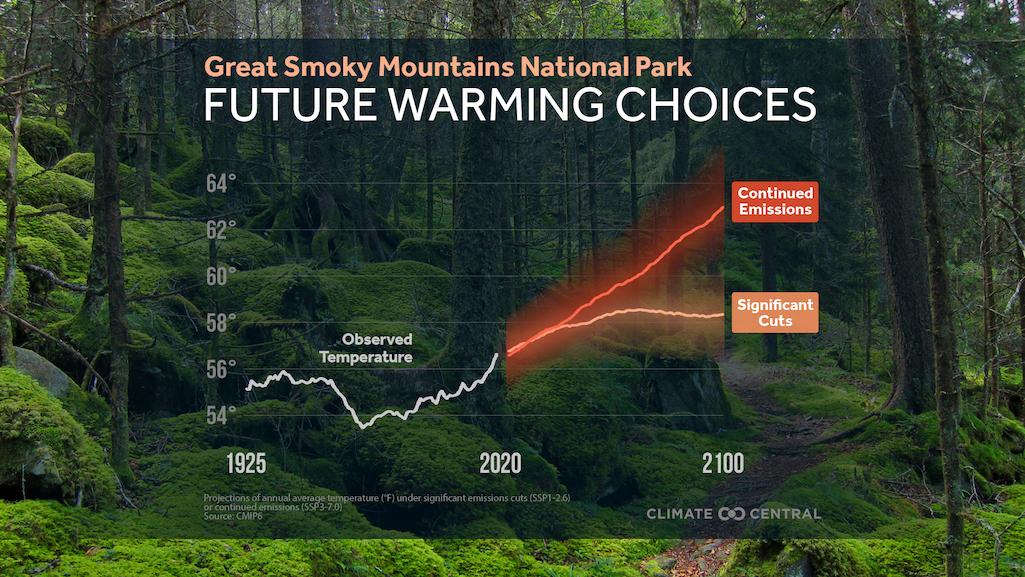

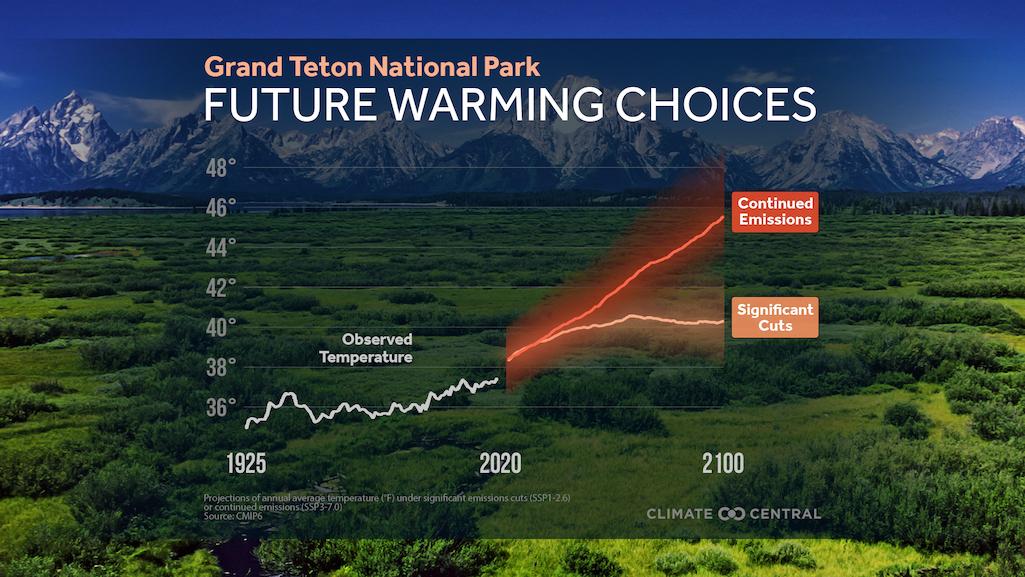

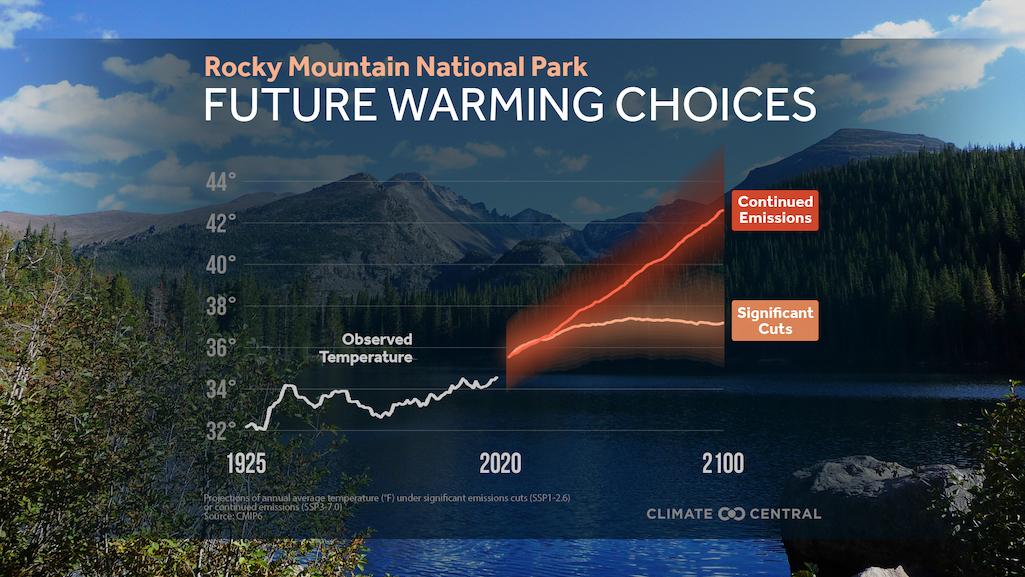

By the year 2100, some parks across the system could see average temperatures up to 11° Fahrenheit warmer than today, the organization said in a presentation released just before National Park Week arrived. Others could see much higher temperatures.

Nicholas Fisichelli, the president and CEO of the Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park, said climate change impacts already are evident in many parks.

"In some ways, there isn't any news here. Climate change is ongoing. We've known that, we're seeing it," Fisichelli said Thursday during a phone call. "You know, we used to talk about climate change in the future tense. And now we talk about in the present tense. That's the reality that we're in now."

Indeed, in a special report, Changing Climate, Changing Parks, the National Parks Traveler staff pointed out how climate change is redrawing the park system's natural landscapes and waters. From Alaska to the Caribbean, warming temperatures, more frequent and potent hurricanes, more intense wildfires, and longer-lasting droughts are drastically changing the wondrous lands and waters that Stephen Mather and Horace Albright encountered a century ago as they set out to piece together what would become the world’s most admired park system.

Fisichelli noted that, "looking out in the future towards the end of the century, the biggest uncertainty in future climate is human behavior. So it's which emissions trajectory we're on; the business-as-usual high emissions trajectory, or if we get onto a low emissions diet, so to speak. And that's the biggest uncertainty in future climate as is our actions as society and the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases we put into the atmosphere."

Among the data Climate Central collected in making its forecast was a 2018 study by scientists at the University of California Berkeley, and the University of Wisconsin. In a report that year they noted that the landscapes preserved within the park system were bearing a disportionately greater impact from climate change than the rest of the United States because a greater percentage of the system is located at higher elevations than most U.S. landscapes. Also, because Alaska has more national park acreage than the rest of the country.

Average temperature projections under differing emission levels for select parks prepared by Climate Central. For projections for more parks, visit this site.

For now, Fisichelli said, humankind's behaviors when it comes to fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions will continue to drive climate change.

"Over the next few decades, regardless of which emissions trajectory we're on, we're going to see continuing change over the next few decades, climate change is going to continue," he said. "Temperatures are going to continue to warm. We're going to continue to see changes in precipitation regimes as well."

In the East at parks such as Acadia, those changes in precipitation have translated at times into heavier rain events.

"We've been having too much water and heavy rain events," said the scientist. "Last year, June 9 of 2021, we had 3 to 6+ inches of rain in just a couple of hours. It washed out roads and culverts and damaged carriage roads in the park and also damaged some of the hiking trails and literally obliterated one of the historic hiking trails [the Maple Springs Trail] that follows a stream on Mount Desert Island.

"The park's now faced with the question, what do you do? Do you build this path back where it was previously? Or do you just sort of walk away from it?" Fisichelli said. "That's no longer a trail in this park? Or, do you try to perhaps move the trail to higher ground outside of the stream bed?"

With such impacts on the ground, scientists and researchers are working to determine how best to respond. How should invasive species, both plant and animal be tackled? Should park managers be preparing to manage for new vegetation that will thrive under the changing climatic conditions? With warming trends climbing up in elevation, should they bring in lower elevation plants that can tolerate those trends?

"Is that even a possibility?" wondered Fisichelli. "How do you even do it? And if you were to carry it out, which species would you utilize?"

These questions are not being considered in a vacuum. The National Park Service last year produced a climate-change planning document designed to guide "NPS planners and managers in developing robust climate change adaptation strategies to better protect park resources and assets today and for future generations."

That 80-page document takes park staff through the assessment of climate change vulnerabilities and risks and the evaluation of climate implications for management goals to possible adaptation strategies and implementation of chosen strategies.

"In addition to numerous challenges already confronting national parks, the NPS now faces the broad-scale threat of a rapidly changing climate, which has the potential to dramatically affect natural and cultural resources under our stewardship. Addressing climate change in the full range of NPS planning efforts is integral to the agency’s ability to meet its mission under conditions of rapid environmental change," the guide's authors wrote.

"Effects of rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, stronger storms, and other climatic changes are already evident in America’s national parks. These include more severe wildland fires and floods, declining snowpack, melting glaciers, rising sea levels, more frequent coastal inundation, and increased erosion," they continued. "Such changes can alter ecosystems and disrupt wildlife; threaten cultural and historic resources; damage buildings, roads, and other infrastructure; and affect visitor experiences and behaviors. Additionally, climate change can magnify the impacts of invasive species, pollution, and many other environmental concerns affecting national parks and their surrounding communities."

At the Schoodic Institute, said Fisichelli, students and graduates early in their conservation careers who hone their skills there will long be dealing with climate change.

"They're going to be spending the next several decades -- really, their whole careers -- responding to climate change and adapting to these changes that already underway," he said. "So these these [Climate Central] figures, I think, to me sort of bring that home. This isn't something that's going to go away anytime soon. And we need to be adapting to ongoing change. And then we need to be getting in mitigation efforts so that in the long term we're not on a high emissions pathway, and all the adaptation measures we're putting in place today aren't sort of overwhelmed by runaway climate change at the high emissions pathway."

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Just more Chicken Little predictions that are destined to be wrong.