A whaler at sea/NPS archives

I’m driving alongside a rocky beach in Quincy, Massachusetts, windows open to the salty sea air, seagulls squabbling over mussels. Hazy clouds drift overhead as I look out across the bay. Today, I’m on my way south from Boston to New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park. As a national parks traveler from New Mexico, I’m clearly out of my element. Yet, I feel an odd affinity with the 19th century whaling ship sailors from New England. After all, they were the gig workers of their day, contracted freelancers and seasonal employees chasing an opportunity for temporary work across hundreds and thousands of miles, for months or even years at a time. Not everyone is suited to the wayfaring life.

Like most of the crew on any whaling expedition, I know that, financially, my travel writing is a similar break-even proposition at best. But there’s also a certain energizing freedom in this untethered work.

However, it isn’t helpful to romanticize or gloss over the difficulties of working in the energy industry, which is exactly what whaling was. Work is a trade-off of opportunities and resources – including human resources. I’ve been reading about such choices in New Bedford Communities of Whaling: People of Wampanoag, African, and Portuguese Island Descent, 1825–1925. It’s an ethnographic report completed for New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park in 2021. I found this fascinating document on the park’s website and decided to travel to New Bedford to learn more about why these people chose to work in the unpredictable and dangerous whaling industry.

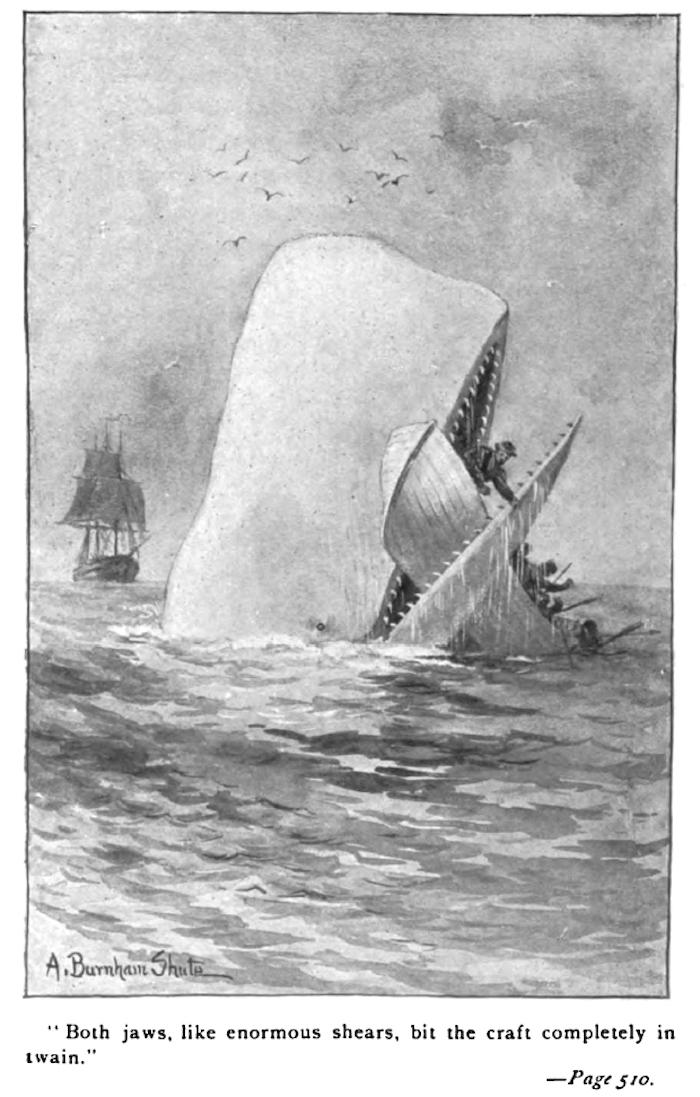

A turn on a whaler provided Herman Melville with the inspiration for Moby-Dick/Library of Congress

In the United States, we have a history of wasting and using up our resources – just look at the megafires burning in our mismanaged forests and the severe water losses in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. It’s like we’ve never stopped whaling, just changed what we’re hunting for, what we’re overusing and taking for granted. Even when other safer, more sustainable ways exist to obtain and maintain what we need.

On the Quincy shore, I pass a beachside hummock named Caddy Park. Here, in 1999, construction workers building a playground uncovered a carefully buried cache of stone tools once used for butchering whales. The indigenous Wampanoag people originally utilized drift whales (whales that washed ashore) shared for the benefit of the entire community, vs. the later, more aggressive methods of pursuit to near-extinction. I glance out my car window at two wind-boarders carving across the water’s sparkling surface; underneath, shallow Quincy Bay is silting in and reportedly polluted with sewage. Drift whales are no longer an option here. I drive on.

An hour later, a sign for New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park appears, the quaint seaside town like a descriptive passage from a Herman Melville novel. The park is, in fact, a small but important memorial to energy industry workers of the past. Whaling ships sailing into and out of port at New Bedford were once as common a sight as today’s fuel tanker trucks hauling gas and diesel on interstate highways across the country. During New Bedford’s whaling boom in the 1800s, whale oil lit the lamps in people’s homes and kept the flywheels of the American Industrial Revolution humming along smoothly. Melville’s descriptions in Moby-Dick of life onboard an 1840s whaling ship – or schooner, brig, or bark, depending on the boat’s size – come alive in the displays at the park's visitor center, in large part because Melville actually joined a whaling crew on an 18-month run at sea.

Many men lost their lives chasing whales from small “whale boats” used to harpoon and kill the massive animals. The tombstones of whalers lost at sea are found as carved stone cenotaphs (literally “empty graves”) lining the sanctuary walls in the Whaleman’s Chapel on the second floor of the Seamen’s Bethel. You can tour the Bethel, built in 1832 as a church for whalers and fishermen. Facing the very real dangers ahead of him, Melville attended religious services there in late December 1840 until he shipped out January 3, 1841, adventurous and naïve at age 21 – like so many of the young men whose etched names hung all around him in the chapel even then, an ominous, silent warning.

Dangerous fuel/energy work has long attracted marginalized workers with few (if any) options. Melville would have found many Africans and African Americans, Native Americans and Atlantic Islanders from Portuguese-held Cape Verde and the Azores, all working side-by-side in the New England whaling industry, whether shipboard or as “along-shore men” on the docks. Park exhibits include a short history on Captain Paul Cuffe (1759-1817), born on nearby Cuttyhunk Island, the son of a Wampanoag mother and an African father originally brought to America as a slave. Cuffe worked his way up from young whaler to skilled seafarer to shrewd merchant, eventually becoming a ship owner and arguably the wealthiest person of color in this country at the time.

But most whalers, and especially people of color, did not share Cuffe’s unusual level of financial success. Instead, whaling provided a way for many desperate Black people in America to escape slavery. Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) fled his enslavement in Maryland and first settled in New Bedford from 1838-1842, where he initially worked as a boat caulker on the wharves. Many Cape Verdeans and Azoreans of that time signed on to whaling crews hoping to escape recurring crop failures and local famines – and the societal prejudice, indifference, and limitations imposed by the continental Portuguese toward the native people of their island territories.

Native Americans, their lands and traditional options vanishing, also joined, and Wampanoag spearfishing and near-shore whaling expertise made them legendary harpooners. Despite the risks and hardships, whaling work offered all of these men a new opportunity for relative freedom, a chance to gain valued skills and earn equal lays, their shares of the ship’s profit, small as those shares might be. Usually, only the captain and first mate, and possibly the harpooner, made enough money to justify going on such hazardous expeditions. It was the ship’s owner, safe in his mansion on the high hill above New Bedford, who reaped all the financial rewards.

The oversimplified image of whale oil burning brightly across a young America is the fiction here. The truth is that whale oil was prohibitively expensive for home use, and only wealthy people could afford it – the same wealthy class owning the industrial manufacturing sites that preferred whale oil as a superior lubricant. Most people used cheaper, dirtier alternative oils made from coal derivatives or camphine, a mixture of alcohol, camphor oil and turpentine. Yet year after year, the whaling ships were sent out, traveling farther and farther to find whales as the fishing grounds played out, sperm whales and then right whales hunted nearly to extinction.

Whaling was a dirty, dangerous business for 19th century sailors/NPS archives

First, down the Atlantic, then around Cape Horn at the southernmost tip of South America, up through the Pacific, and eventually all the way from New Bedford to Utqiaġvik, or Barrow, Alaska, above the Arctic Circle, learning from Alaskan Iñupiat people how to catch bowhead whales. These could be five-year ocean voyages, sailing some of the world’s most treacherous seas, bringing back less and less oil, selling the bowhead whales’ baleen for use in fine ladies’ corsets and hoop skirts. It was sinking profit margins, rather than concern for the increasing risks to the crews’ lives, that etched the cenotaph of the whaling industry.

And so, whaling ended – not coincidentally as petroleum production was introduced and affordable kerosene developed, with government taxes on previous alternative oils making those products now prohibitively expensive.

Today, no one laments our lack of whale oil. We’ve moved on to new energy resources – which shows that we can shift gears and pursue new and more effective ways to meet our needs. To this day, though, marginalized workers with few options are still drawn to the money of dangerous oil and gas work, from roustabouts to tanker truck drivers. As we drill off-shore and on our protected lands, fracking our sands for the last deposits we can find, all the way to the Arctic Circle, aren’t we just chasing whales? Who is making the money here, and who is taking the actual risks? We have other, safer options that could be supported and pursued.

Down at the New Bedford harbor, I stand before a cast monument titled “Commonwealth of Toil.” It reads:

On this site in 1936, Cape Verdean and Portuguese dockworkers formed Locals 1413 and 1465 of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA). Prior to organizing, these dockworkers were chosen daily, based only on their physical ability, and had none of the benefits, security, or decent wages that came with the union.

Rather than being a stagnant, moldy reliquary to stereotypes of whaling lore, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park is instead a thought-provoking reminder that mismanaged resources – including human lives – do not last forever. It provides new insights and opportunities to discuss racial disparities, working conditions, and renewable energy.

Traveler footnote: Two Brothers, a historically significant whaling ship found in 2008 by maritime heritage archaeologists, is now included in the National Register of Historic Places—the official list of the nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Two Brothers was captained by George Pollard Jr., whose previous Nantucket whaling vessel, Essex, was rammed and sunk by a whale in the South Pacific, inspiring Herman Melville's famous book, Moby-Dick. Pollard gained national notoriety after the Essex sinking, when he and a handful of his crew resorted to cannibalism in order to survive their prolonged ordeal drifting on the open ocean. Read more.

Barbara “Bo” Jensen is a writer and artist who likes to go off-grid, whether it's backpacking through national parks, trekking up the Continental Divide Trail, or following the Camino Norte across Spain. For over 20 years, social work has paid the bills, allowing them to meet and talk with people living homeless in the streets of America. You can find more of Bo's work on Out There podcast, Wanderlust, Journey, and www.wanderinglightning.com

Follow @wanderlightning [email protected]

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment