Joseph Speece was a magician at coaxing life from the water-starved prairie of eastern Wyoming. He so perfected dryland farming that his harvests of sweet corn, potatoes, millet, cucumbers, and muskmelon routinely won blue ribbons at the Goshen County fairs. But he and his fellow residents of tiny Empire couldn't cultivate a bountiful life there.

Despite the Wyoming state motto, Equal Rights, a black community was not welcomed in the state, and in less than 20 years years Empire was slowly reclaimed by the windswept prairie.

Speece and countless others from all walks of life -- former slaves, Latinos, Civil War veterans, women, members of the LGBTQ community -- took part in the grand land rush that the Homestead Act of 1862 launched. It was a rush that required grit, ingenuity, perseverance, and even a little luck if you wanted to grasp free title to 160 acres or more simply by making a life on the land for five years. "Simply," of course, is an over simplification of what it took to "prove up" your existence on your land.

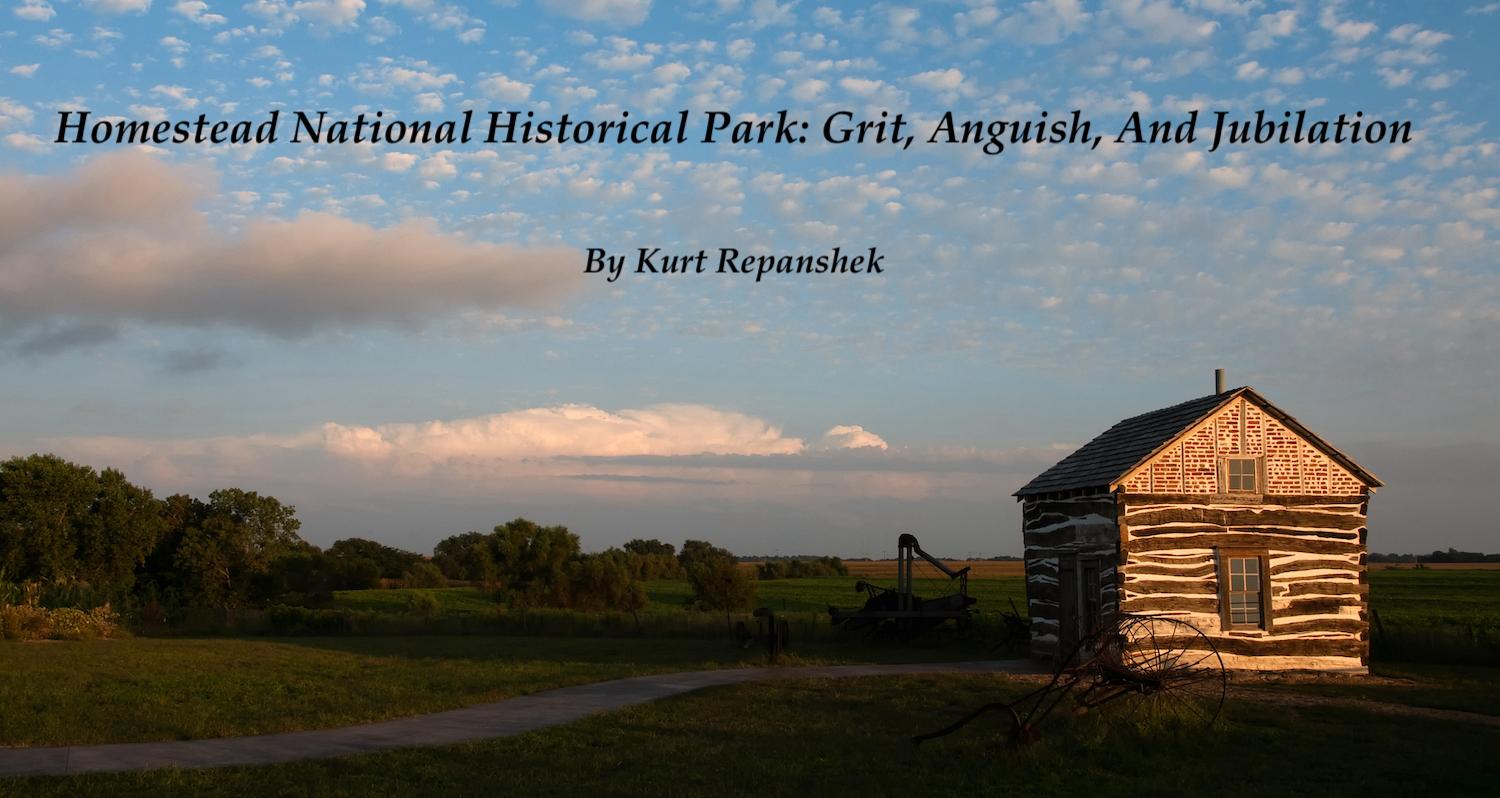

But while the prospect of free land that the Homestead Act promised sounds typically American -- hard work and determination will lift you up -- the stories you can explore at Homestead National Historical Park in southeastern Nebraska reflect both jubilation and anguish, deprivation and self-determination. Not only were those once enslaved persecuted and threatened in places they tried to homestead, but Native Americans who long lived on the "free land" the federal government was giving away were both displaced and, if they wanted to claim back some land through the act, had to renounce their tribal connections and apply for U.S. citizenship.

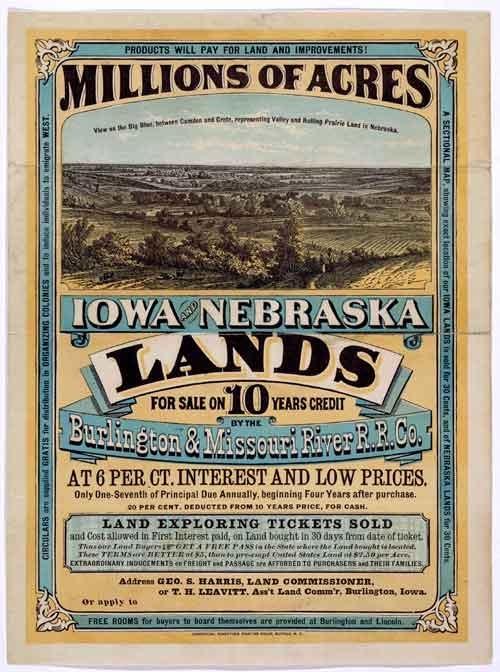

The Homestead Act spurred an incredible amount of advertising for "free" land/NPS archives

The differing views on the very existence of Native Americans on the land are explored in the park's visitor center. While John Quincy Adams in 1802 ignored their existence -- Shall the fields and the valleys, which a beneficent God has formed to teem with the life of innumerable multitudes, be condemned to everlasting barrenness? --, artist George Catlin, who traveled the plains with various tribes in the 1800s, feared for their plight -- The Indians of North America were once a happy and flourishing people.

Their differing views, though a generation apart, highlighted part of the controversy that arose out of the Homestead Act.

"For Native Americans, that land had been home for untold generations, and so native land dispossession is a huge, huge impact by the Homestead Act and by other public lands laws," Jonathan Fairchild, the park historian, explained as we walked the 160 acres that Daniel Freeman claimed as the first authorized homestead in 1863. "You know, those hundreds of millions of acres of land that were offered up for free, it came from Native Americans all across the country. And so in some parts of the country, native tribes had been removed, forcibly removed, maybe decades before the Homestead Act, but there's still that direct connection. In other places, perhaps some of the most iconic, most famous homesteading stories like the Oklahoma land rush -- you know, the Sooners and the Boomers right? -- that is directly tied to the Dawes Act, and the taking of Native American land to open up under the Homestead Act. And so I think that our park here does a pretty good job of making sure that visitors see that side of the story and understand that side of the story."

The Dawes Act was the product of U.S. Sen. Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, who believed Native Americans would benefit from living on farms and his legislation turned Indian reservations into 160-acre allotments, notes the Park Service, adding that "[T]his allowed the federal government to break up tribal lands further."

"Native Americans could become citizens by essentially renouncing their tribal citizenship," Fairchild said. "And so it did occasionally happen, where Native Americans could homestead under the Indian Homestead Act [of 1864]. But generally speaking, you don't see a ton of that."

What you did see under the Homestead Act was an acceleration of Native American dispossession of lands they had roamed for millennia and later would formally gain through treaty agreements, or so they thought. And to them, land was not to be owned, but to be used by all.

Homestead National Historical Park overflows with such stories. They start with Daniel Freeman, who filed his claim for the 160 acres on which the park sits at 10 minutes after midnight on January 1, 1863, the day the Homestead Act took effect. He did indeed tame the rolling prairie, and lived there until in died in 1908.

To better understand the settlement rush the Homestead Act launched, I caught up with Jessica Korgie, a park guide who lately has been delving into the segment of Black homesteaders. As we talked on the Prairie Plaza, a place to sit beneath the shade of trees while listening to chirping birds and admiring a sweeping view across the tallgrass prairie that anchors the Freeman homestead, Korgie offered some perspective about those who tried to leverage the Homstead Act.

"If you were talking about many stories stemming from the Native American side, it's a lot of heartbreak," she told me. '"And it's still heartbreak. And then you hear the European side, you hear heartbreak and success. But then there's the side of people that were freed from enslavement. The work through the Black Homesteaders Project, at least for me working on this project, has shown a big side of hope within the Homestead Act, which has made it very invigorating and fun and a joy to work with descendants, as they discover, 'Oh my gosh, my family's part of the story.'"

Various ads promoted the prospect of "free land" in the country/NPS archives

Through the Black Homesteaders Project the park guide has been able to peer into the past and get a grasp of the struggles endured by Blacks who wanted to take advantage of the Homestead Act.

"I'd say it was just good honest grit. A dream, a desire," Korgie replied when I asked her what drove Blacks, some of them recently freed slaves, to pack up and, in many cases, leave the only homes they ever knew with a determination and a trust of themselves to venture onto the Western frontier. "A first step into freedom, of living your own life. And here's this law that's allowing you to do that. And, you know, I did not step personally in the shoes of these families, but hearing stories from descendants, and some descendants that actually heard these stories being passed down, it was such a hopeful story. How people learned about the law to take part in the law."

Empire, Wyoming, was one such destination beginning in 1908 and, sadly, one that didn't survive against the challenges of the times. Another was Nicodemus, Kansas, where the story of Black determination is told at Nicodemus National Historic Site. It was there in 1877 that a group of Blacks, fleeing the Ku Klux Klan in Kentucky, settled.

"Despite the isolation, the challenging climate, and the lack of good railroad connections, the community took root. Churches, stores, and gathering places served 600-700 people spread out across the Kansas countryside," wrote Professor Bob Pahre in a 2013 article for the Traveler. "This was the first Black homesteading community in the West. It thrived until the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression of the 1930s, when people started to move to the cities to look for work."

Piecing together a complete racial picture of those who leveraged the Homestead Act isn't easy. The forms the would-be homesteaders filled out didn't include a check box for "race." While you'd likely be right to assume a Knudson, Olson, or Swenson was a North Dakota homesteader with Norwegian background, it's impossible to categorize the race of a Smith or Jones.

"It's not like you can go find all the European people and let's go find all the African American people," explained Korgie. "So it does take a significant effort to research censuses, and even try to get back to documents of enslavement if you can. It's just not easy work."

While the Homestead Act offered great promise, it wound up being a 50-50 proposition for the nearly 4 million who hoped to take advantage of it. Once they chose the acres they wanted to settle and filled out the paperwork, they needed to tame that land and, over a five-year-period, improve it by building a home, farming it, making a living. At the end of those five years, they needed to get at least two witnesses to attest to their having "proved up" on the land.

"Millions of people took advantage of the Homestead Act," Fairhchild told me, "although only about 50 percent were successful in proving up the land. So making it that five years, meeting all the requirements, and earning the patent or the deed to the land, in total about 1.6 million received land under the Homestead Act."

The last homestead claim went to Ken Deardorff, a Vietnam vet who in 1974 staked his claim to 50 acres along the Stony River in Alaska. You can find the Allis Chalmers 1945 Model C tractor he used to work his land in the Heritage Center.

But not everyone could tell a success story. Taming river bottom land with good soil for crops was one thing, busting sod in North Dakota in the howling wind is another. The Homestead Act fed hope and dreams, but facing reality was another thing.

"Dreaming of a better life, my wife and me. Swallowed their promises, how it all would be. And I rode the railroad train to a plow with hope and steam, but I never knew how loud the wind could scream. Three-hundred-and-twenty acres to make man a king, the winter come a-howlin', so bitter, so mean. And the summer sun tried to burn the soul right out of me, I never knew, I never dreamed. How the railroad said this would be a garden of eden, the papers claimed rain would follow the plow. My children's eyes are wild and hungry, and I'd like to go back home, but I don't know how." -- Dave Stamey, Montana Homestead 1915, from Western Stories.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

A. Johnson, if you want to debate aspects of this story, please reach out to me via email.