Resource management officer Neil Vinson shows off the pollinator garden at Fundy National Park/Jennifer Bain

Pollinator Gardens And Other Reasons To Love Fundy National Park

By Jennifer Bain

It’s not a showy garden, or even very colorful, but it is a critically important one that helps migrating monarch butterflies, at-risk yellow-banded bumblebee and other less glamorous pollinators find food.

Even so, Parks Canada resource management officer Neil Vinson admits to receiving some flak when he took over the garden near the Headquarters Visitor Information Centre at Fundy National Park.

“It’s in a really high visibility spot and there was pressure to make the garden pretty and fill it in,” Vinson tells me during an August visit. But beauty aside, his main mission was to create a pollinator garden.

To the sea of yellow, green and white plants and flowers, Vinson sourced a few varieties with pink and purple hues (all hyper local, of course). To create eye appeal, he added six brightly painted cedar block bee houses, logs and rock features shaped to double as water features.

A brightly painted bee house adds eye appeal to Fundy's pollinator garden/Jennifer Bain

“I’m a plant person and I seem to have inherited the garden in 2019, but I’m not an expert gardener by any means,” says Vinson. “I’m trying to do my best with this space. Native plants are not that easy to find at local nurseries, but ditches — that’s where I’ve had luck finding a lot. If I see something growing in a ditch, chances are it will survive growing in this garden.”

Established in 1948, Fundy — on the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick — offers access to the world’s largest tides. People come to kayak at high tide and explore the Atlantic Ocean floor at low tide. But inland there’s plenty of hiking, biking, camping and paddling through 206 square kilometres (80 square miles) of Acadian forest as well.

The pollinator garden sits behind a parking lot and picnic area on a bluff over the Bay of Fundy. It’s within eyeshot of a triangular but conventional garden — full of predictable annuals — in the middle of an intersection in front of the visitor center.

The garden is in area of full sun that’s highly exposed to wind. Several types of fencing keep browsing deer at bay from thing like American Mountain-ash and Red-Osier Dogwood. “I don’t mind if they browse some of the things,” allows Vinson, “but I just don’t want them to kill the plants.”

The pollinator garden uses tubes like this to combat browsing deer. Here is protects American Mountain-ash/Jennifer

A virtual guided tour of the pollinator garden is in the works for the Parks Canada mobile app, but I get an actual tour as Vinson shows off many of his 70-odd native plant selections, from Grass-Leaved Goldenrod and Pearly Everlasting to Swamp Dewberry, Fireweed and Willowherb.

For those park visitors who stop long enough to educate themselves, signage in the pollinator garden explains how bees, butterflies, flies, moths, mice and birds provide a vital service to our planet by helping plants reproduce by carrying pollen from flower to flower, allowing them to produce fruits, nuts and seeds.

Some pollinator species are in severe decline because of loss of habitat and food sources, pollution, pesticides, diseases and climate change. Threats to pollinator populations are a major problem for humans, signs reveal. “Almost all of the food we eat depends on the work of pollinators.”

A caterpillar munches on native species in Fundy's pollinator garden/Jennifer Bain

An estimated 28 per cent of bumblebee species in North America are at varying levels of risk of extinction. This garden provides important habitat and food for species such as the Yellow-banded Bumble Bee (a species of special concern).

Vinson calls Monarchs, another species of special concern, a “great spokesperson for pollination.”

When they’re in their caterpillar stage, endangered Monarch butterflies only eat milkweed. Since milkweed doesn’t naturally occur in Fundy, Vinson’s pollinator garden boasts flowers that can offer nectar to adult Nonarchs who will feed on them all summer and give rise to the next generation who will migrate to Mexico in the fall.

Visitors who want to see milkweed and Monarch caterpillars are directed to find one of the park’s sister gardens across the UNESCO Fundy Biosphere Reserve.

This rock has a natural indent that serves as a water feature/Jennifer Bain

And for those who wish to take up the call to help, the park offers four suggestions:

• Create your own pollinator garden with flowers, shrubs and trees that are native to your region. Find Fundy’s free booklet “Pollinator Garden Project: Plant A Habitat.”

• Embrace chaos by letting your garden grow wild and giving pollinators places to hide. Resist raking leaves and don’t mow your whole yard.

• Help scientists by snapping pollinator pictures and reporting your observations to iNaturalist.

• Reduce your environmental footprint and help all living beings by reducing your waste and taking action against climate change.

“The biodiversity crisis and mass extinction can weigh heavily on a person’s conscience,” Vinson admits. “Creating a garden with native plants is something a person can do to make an actual difference, whether it’s a pot of milkweed on a balcony or a grove of native trees on your acreage. Anything will make a measurable difference.”

Fundy's pollinator garden is important, if not colorful/Jennifer Bain

In 2021, Vinson proudly points out, Fundy discovered 48 new species of insects and 55 per cent of them were found in the pollinator garden.

While the pollinator garden “should look wild,” it shouldn’t be wild and must managed. Vinson must “keep the weeds down and make it appealing to the eye and not just to pollinators,” and that's exactly what I find him doing and leave him doing when we’re done chatting.

Directly across from the pollinator garden is the MacLaren Pond Medicine Trail, a short and easy trail created with Mi’kmaq insight about medicinal plants from the Fort Folly First Nation.

Fundy's MacLaren Pond Medicine Trail features signage created with Mi'kmaq insight from the Fort Folly First Nation/Jennifer Bain

“In the last year, we renovated the trail and they installed a beautiful boardwalk,” says Fundy’s Indigenous relations advisor Shannon Ward. “It’s quite amazing once you get up close to it. It’s an important place for us.”

There are five interpretive signs, all with Indigenous artwork. One details how sweetgrass, sage, cedar and tobacco — which aren’t necessarily found in Fundy — are considered the four sacred medicinal plants used for mental, spiritual and emotional healing. During a smudge ceremony, sacred plants are lit on fire and then gently smothered to create smoke. People pray to honor the four directions and ask to be cleansed of the negativity around them. As they draw the smoke towards themselves, it attaches to the negative energy and carries it away.

The pond at the MacLaren Pond Medicine Trail has an interesting back story/Jennifer Bain

Of course, it’s illegal to pick anything in a national park and Parks Canada adds a caveat that misusing plants for medicine can be seriously harmful. As one sign reads: “All living things on Mother Earth have a spirit and must be respected. Ask the plant’s spirit for help.”

Ward hopes to eventually see if sweatgrass will grow along the medicine trail. And he hopes to see audio added to the panels "as another way of sharing Indigenous knowledge. If someone can’t see the panel, at least they can hear the panel. It’s a small area, but it’s very impactful.”

The pond, too, is deceptively small. It’s known as a “bottomless lake” — although it isn’t — and is the footprint of an ancient glacier. As the glacier melted, a little chunk was left behind. Streams blanketed the valley bottom with gravel, insulating the ice chunk. As that chunk slowly melted, the gravel around it collapsed forming this 20-metre (65-foot) deep kettle pond and the wide bowl that surrounds it.

Cedar — one of the four sacred medicinal plants to Indigenous Peoples — is being grown alongside the MacLaren Pond Medicine Trail/Jennifer Bain

I always wonder what people see when they visit a park. For every popular spot, there’s usually an equally deserving place that gets short shrift. Whichever spot you are at, you can rush by or find out more about what you’re seeing.

Fundy’s most photographed location is its covered bridge in the Point Wolfe area near Shiphaven Trail. It’s a beauty and the only one of its kind in a Canadian national park. The current red bridge was built in 1992 but modelled on an earlier version from 1910.

The bridge spans the Point Wolfe River, a tidal river that was once the center of a lumber operation with a mill that ran from 1826 to 1921. While the mill brought jobs for 50 people, sawdust and waste dumped into the river (a common practice back then) ruined it for fish and the dam blocked migration for the Atlantic salmon.

Part of the dam was removed in 1985 to help the river recover, but a few pieces were left to show people how the dam was built. From a viewpoint facing the bridge, signs say that rare Livelong Saxifrage and Bird’s Eye Primrose grow on the north-facing cliff across the river among slow-growing trees stunted by the wind and cold. But it’s impossible to see if that’s still true without binoculars.

The most photographed thing in Fundy National Park is this covered bridge, but if you get below it you can see evidence of the area's logging past/Jennifer Bain

I don’t need binoculars when I join a gaggle of kids for the Herring Cove Beach Exploration and walk the ocean floor at low tide looking for creatures. Experiencing the Bay of Fundy’s tides and tidal flats is a big draw for the park. The difference between tides can be as much as 12 metres (40 feet) and there are two low and two high tides each day.

“This is where we find the majority of the species that would be on our park bucket list,” interpretation office Evan Houlahan tells the crowd. Indeed, Parks Canada puts out an Xplorers booklet at many of its parks and sites, and the one for Fundy directs kids to Herring Cove to find sideswimmers, periwinkles, barnacles, hornwrack, soft-shelled clams, scallops, knottedwrack, dogwhelk and crabs.

We scoot about the intertidal zone with plastic containers, looking under rocks and among the seaweed, and bringing everything we find back to Houlahan for identification.

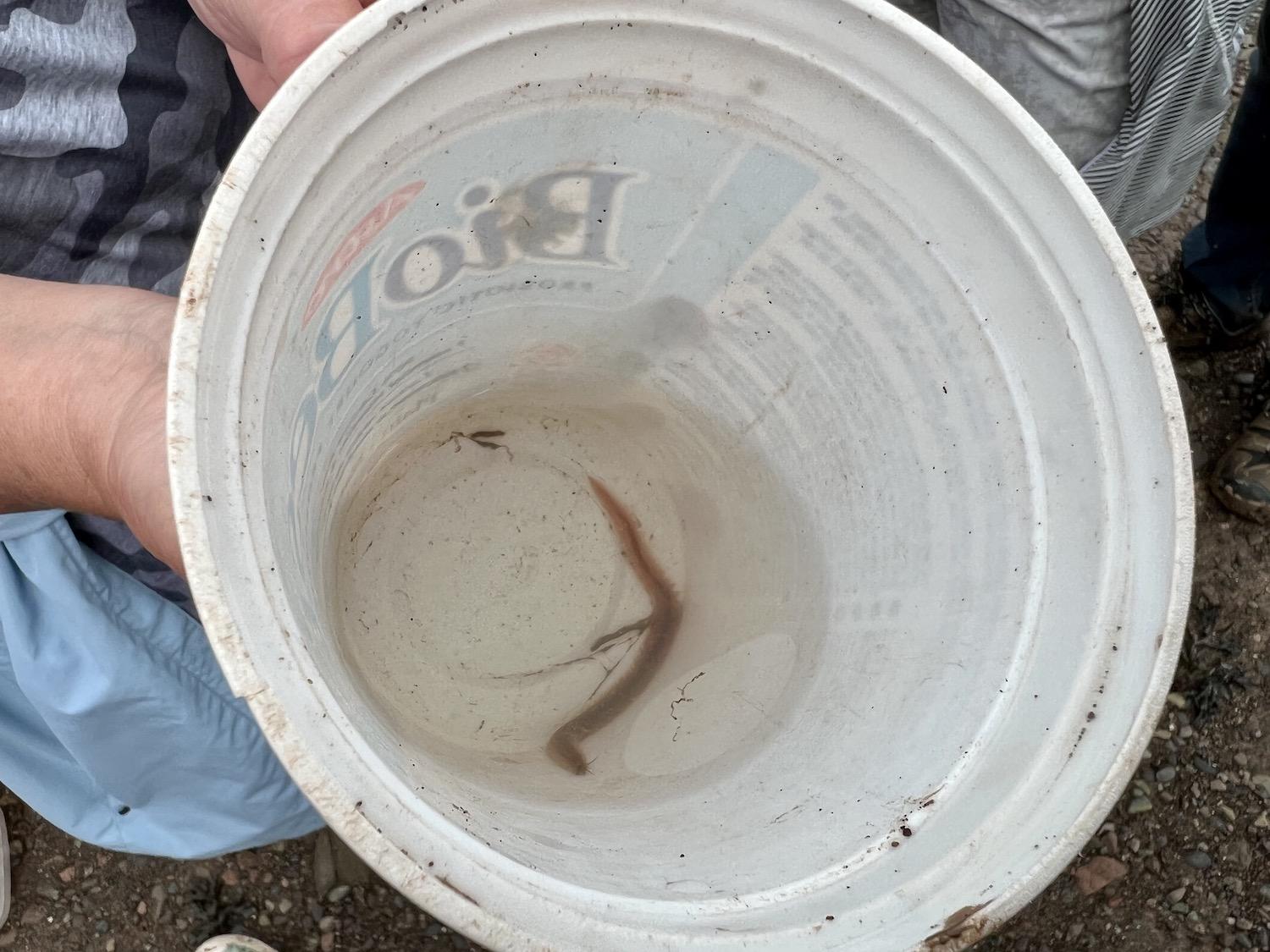

While exploring Herring Cove Beach at low tide, kids find this clam worm/Jennifer Bain

“We’ve found all three of our different species of crabs,” he declares. “There’s a hermit crab and a rock crab, but all the other crabs — every single one — is the European green crab and it’s actually an invasive species.”

But the star of today’s low-tide show has to be the clam worm — a wiggly pinkish-brown creature with plenty of tentacles that can grow up to 30-centimetres (12-inches) long. “It almost looks like a swimming centipede, and they usually burrow in the mud,” says Houlahan, before adding “we practice catch and release so we’re going to return our friends to some of the intertidal pools.”

While I dip my toes in the ocean, I never do swim in Fundy, though I do eyeball its solar heated saltwater pool and admire its lakes and rivers.

Before a guided kayak on Bennett Lake, I meander down Caribou Plain Trail, named for herds of woodland caribou that called this area home until 1907.

Parks Canada staff lead an after-hours paddle around Bennett Lake/Jennifer Bain

On a quiet two-kilometre (1.2-mile) loop, I take in the Acadian forest, wetlands, small lakes and a raised peat bog, and read about a spruce budworm invasion in the 1970s that wiped out mature spruce and fir. What I don’t see are any beavers or moose.

It’s not nearly as showy as the ocean and the Bay of Fundy, but Bennett Lake is a gem. It’s one of just two waters in Fundy where you can fish (with a national park license) and there’s a small, unsupervised beach. Outdoor Elements rents kayaks, canoes and paddleboards.

Led by two park interpreters, I join a leisurely kayak around the lake at dusk. We still don’t luck into a moose sighting, but take great delight in American Black Ducks, green frogs and bullfrogs before reaching the furthest end of the lake and spotting beavers. We stop paddling so as not to disturb them and watch as they intently plow through the water in search of trees, woody plants, sticks, grass, water lilies and whatever else catches their eye for a meal or for their lodges.

Add comment