Rising Temperatures Take a Toll on Turtles

Hot sand means that more sea turtles are born female, threatening vulnerable species. Beach nourishment projects may be making this trend even worse at Cape Hatteras National Seashore and other coastal parks.

By Kim O’Connell

One sunny morning at Cape Hatteras National Seashore in 2021, the commotion on the beach was fascinating, moving, and indescribably cute. Dozens of baby loggerhead sea turtles were crawling over each other to work their way out of a depression in the sand, in a highly anticipated event known colloquially as a “boil.” Their flippers working overtime, the newly hatched reptiles made their wobbling way instinctively towards the Atlantic.

These turtles were among the nearly 20,000 live hatchlings that emerged from the 315 sea turtle nests that were recorded at Cape Hatteras last year. Sea turtles are a constant source of fascination and delight for national park visitors, who frequently volunteer to watch nests before they hatch, report sea turtle sightings to biological technicians, and attend sea turtle nest excavations, according to park spokesman Michael Barber.

“Visitors show a lot of interest in sea turtle conservation efforts,” Barber says. “We are grateful for so much public support in protecting and respecting these threatened and endangered species.”

But throughout the nation’s coastal park units, land managers and scientists alike are paying close attention to how climate change and other environmental concerns are impacting sea turtle species. This summer, numerous media outlets reported that nearly all the sea turtles hatching on Florida beaches were female, a gender imbalance that could have widespread impacts on the future of these already vulnerable species.

Of the seven species of sea turtles worldwide—the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, Kemp's ridley, and olive ridley sea turtles—all except for the flatback are found in U.S. waters, and those six are listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Overfishing, habitat loss, coastal development and artificial lighting, and pollution have all contributed to turtle vulnerability. The impacts of climate change—warming oceans, worsening storms, and shifting weather patterns—present a dire forecast for many turtle populations.

Warming Warning

Along with alligators and crocodiles, most turtles are subject to a phenomenon known as temperature-dependent sex determination. If a turtle's eggs incubate below 81.86° Fahrenheit (27.7° Celsius), turtle hatchlings will be male. Temperatures above 88.8° Fahrenheit (31° Celsius) will result in all females. Anything in between results in a mixed-gender nest. So, the hotter the sand in which a sea turtle nests, the more likely it will result in mostly or all female turtles. While fewer males than females are needed to sustain healthy populations, obviously when turtle nests produce no males at all, the reproductive cycle grinds to a halt, putting the species’ future at risk.

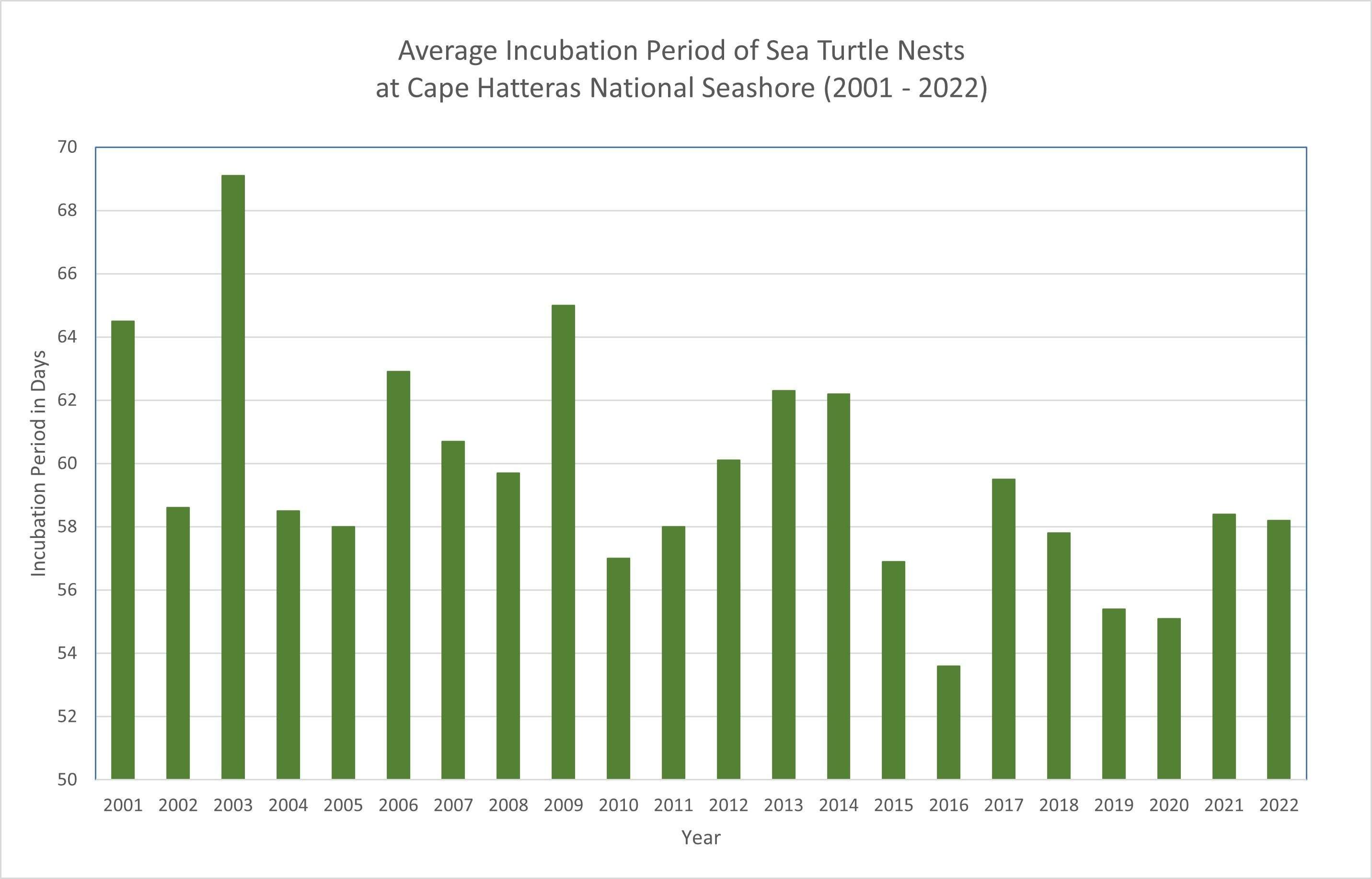

A table of average incubation periods for sea turtles at Cape Hatteras National Seashore between 2001 and 2022. Hotter temperatures mean shorter incubation periods and more female turtle hatchlings. / Seaturtle.org

This is exactly what’s happening in Florida.

"Scientists that are studying sea turtle hatchlings and eggs have found no boy sea turtles, so only female sea turtles for the past four years," Bette Zirkelbach, manager of the Turtle Hospital in Marathon, Florida, told Reuters. “The frightening thing is the last four summers in Florida have been the hottest summers on record.”

Despite the headlines, a gender imbalance is not uncommon in Florida sea turtle populations, simply because Florida is subtropical and hot summers are the norm. Now, however, researchers have determined that more sea turtles are hatching as female farther north in North Carolina, where historically there was more of a male-female mix.

Dr. Stephanie Kamel, an associate professor in the department of biology at the University of North Carolina - Wilmington, is part of a team conducting ongoing research about nesting site selection in sea turtles and how that affects their thermal biology.

In a 2021 paper published in the science journal Ecosphere, Kamel and her coauthors Kaitlynn Shamblott (also of UNC-Wilmington) and Jaymie Reneker of Ecological Associates of Jensen Beach, Florida, investigated how beach nourishment projects affect sea turtles in particular. Beach nourishment is the process in which sand is dredged from the ocean and deposited on land to extend beach area, create and sustain habitat, and prevent erosion. The researchers concluded that these nourishment activities tend to heat up the sand and contribute to a gender imbalance that is already exacerbated by a warming climate.

A rare leucistic sea turtle -- meaning one lacking in melanin -- spotted by park biologists at Cape Hatteras this summer. /NPS

The study involved eight beaches that are known loggerhead turtle nest areas along the North Carolina coast, including two that flank or adjoin Cape Hatteras—the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge on the north end of Hatteras Island and a site near the town of Buxton, not far from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. The researchers concluded that beach nourishment activities are a “significant predictor of mean monthly sand temperatures” at these sites and that “nourished beach sections are, on average, 0.4°C [about 0.72 degrees Fahrenheit] warmer than their unnourished counterparts.”

Hotter temperatures mean reduced incubation periods and thus more females, Kamel says. On Bald Head Island, North Carolina, she notes, the incubation duration of loggerhead nests decreased by an average of seven days over the past 25 years, meaning that the percentage of female hatchlings produced has increased from about 55 percent in 1991 to about 88 percent in 2015. Although no similar long-term evaluation has yet been done for Cape Hatteras, the trend lines are likely to be similar up and down the Carolina coast.

“One male can fertilize a lot of females,” Kamel says. “You don’t need a 50-50 ratio to have a robust turtle population. But if you have only a few males, we run into problems of genetic diversity.”

To gather data, the team looked at sand characteristics, Kamel explains.

“We did a very initial study where we just sampled sections of the beach that hadn’t been nourished and had returned to a natural state,” she says. “We collected the sand and measured its albedo [reflectivity], and then we compared those characteristics between natural and nourished beaches. Nourished sand was darker and warmer than natural sand.”

Searching For Solutions

Kamel is now working with other researchers to develop models that can help predict how nourishment could affect beaches in other areas. They also plan to coordinate with land managers from the National Park Service, the Army Corps of Engineers, and other interested parties to develop management plans to protect turtle nests from overheating due to beach nourishment.

“It’s one thing to say the sand is warmer but have no plan,” Kamel says. “Now we have some data. We’ve found some patterns. We’re going to study this more, then we will come up with some ideas and will have conversations with managers. Can we think about dredging the nourished sand in another place? Can we test the sand before we put it on the beach? Do we shade the nests? Do we water them to cool them down?"

In the meantime, the Park Service is continuing to monitor and manage threats to sea turtles at coastal national parks such as Cape Hatteras. The park website has published two annual reports on sea turtle conservation activities (for 2017 and 2018), and after a pandemic delay, spokesman Barber says that the park is now working on an updated report with data from the past few years. But the park's outreach on turtle activity continues. This summer, park biologists posted a photo of a nearly white leucistic baby turtle they’d found, a genetic deviation that they see only a few times a year. (Leucistic means lacking melanin, vs. albino, which means no melanin at all.) On Facebook, the post was shared 420 times.

Whether it’s cute photos on social media or scientific research, Kamel says, “we’re keeping sea turtles in the people’s consciousness. A world without sea turtles will keep on turning, but it would be diminished.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places