In 2022, you could rent one of two equipped tents at Fort Beauséjour-Fort Cumberland National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

The Chignecto Isthmus sounds magical — “a quiet landscape of salt marshes and rivers” on a narrow strip of land that connects New Brunswick to mainland Nova Scotia. Even better, it’s home to four national historic sites that remind us about the clash between France and Britain for power in North America in the 1750s.

So when I’m on a summer road trip exploring two national parks in New Brunswick, I earmark a half day to check out what’s collectively known as Chignecto Isthmus National Historic Sites.

I wing it, not arranging to meet any Parks Canada guides, and not knowing any more than what I read in the 2018 management plan for the sites. Management plans usually guide the next decade, and the vision for this site stood out: “As visitors from across Canada and beyond marvel at the breathtaking landscape of the Chignecto Isthmus and its vast expanse of dykelands, they are captivated by four must-see destinations offering an array of meaningful experiences and learning opportunities.”

The pandemic, of course, derailed everyone’s plans, so I suspect the ambitious vision will still be a work in progress. But the sites are all within an hour’s drive of Moncton and it’s a perfect day for an educational drive.

Stop 1: Fort Beauséjour-Fort Cumberland National Historic Site

Interpretive panels help you imagine what life was like when this was an active fort/Jennifer Bain

There’s good reason to make this vibrant New Brunswick spot — home to one of Canada’s oldest forts — the gateway to Chignecto Isthmus National Historic Sites.

The star-shaped fort is something tangible to explore, there’s a visitor center and museum, plus extensive grounds that overlook the Tantramar wetlands and the Bay of Fundy. In the 2022 season, people could camp within the fort walls in an 18th century-style tent.

“Though only one fort, Fort Beauséjour has had two names, served two empires, and is a place with countless tales to tell,” explains Parks Canada in a brochure.

There are tangible remains of a fort at Fort Beauséjour-Fort Cumberland and you can even explore old casements/Jennifer Bain

For those who like bullet points, it offers these six that relay the crux of the story:

• The Isthmus of Chignecto lay within Siknikt, one of the districts of Mi’kma’ki, the traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq people.

• Acadians settled the region in the 1670s.

• In 1750-1751, the French put a fort atop Beauséjour ridge to protect strategic interests in the area.

• In June 1755, British and New England troops captured the fort from the French .

• In 1755, the Nova Scotia Council used the fact that the Acadians didn’t really help defend the fort as one of the reasons to begin a mass deportation in the region. The fort was used as the deportation’s initial headquarters and prison.

• In November 1776, under the name Fort Cumberland, this same fort witnessed a British garrison rout a rebel force form the United States under British-American soldier Jonathan Eddy.

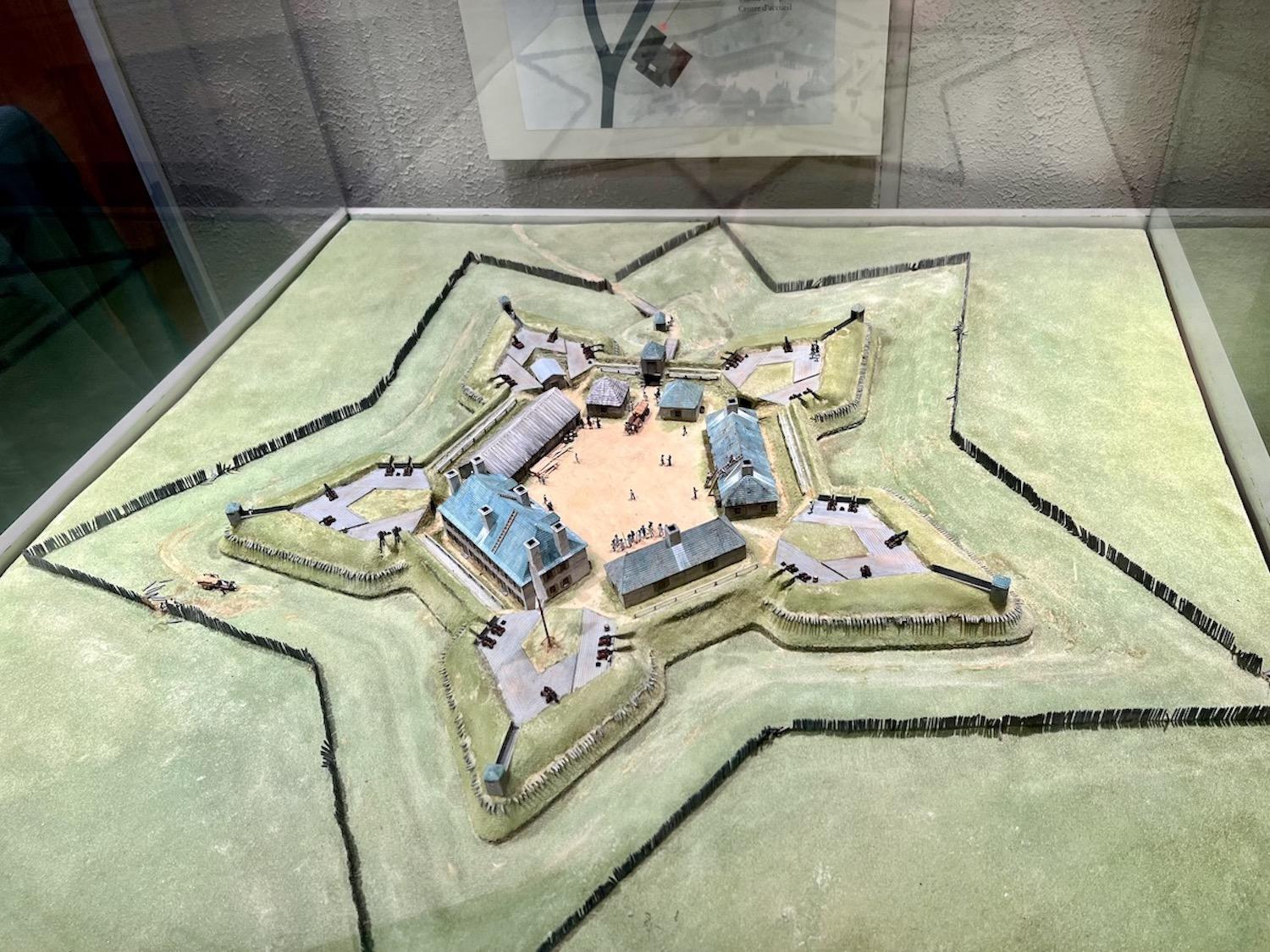

In the visitor center museum, a model shows how the star-shaped fort looks from above/Jennifer Bain

Star-shaped forts, perfected by Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban and taught to all French military engineers, had low walls protected behind long sloping earthworks called glacis which deflected or absorbed cannon-fire.

"A star-shaped fort with its many angles and corners and very few flat, straight walls, was difficult for the enemy to hit with cannon fire," I learn on a GPS-triggered guided tour for this site available on the Parks Canada mobile app. I find the bite-sized nuggets of information to be exactly my speed as I stroll around by myself.

Designated a national historic site in 1920, this fort lies within the UNESCO Fundy Biosphere Reserve.

Near Fort Beauséjour-Fort Cumberland, the Aulac Big Stop gas station salutes sandpipers and other shorebirds that stop in this area to fuel for the migration to South America every summer/Jennifer Bain

But it's not just military history here. I'm fascinated to learn that the Tantramar marshes form one of the largest tidal salt marshes on the Atlantic coast. For thousands of years before European contact, Indigenous Peoples harvested the plants, birds, mammals and fish that thrived where fresh and salt water met.

Now the marshlands are best known for being on a major lane of the Atlantic migratory bird flyways. Birds pour in the upper Bay of Fundy every summer, and the dykelands surrounding the site have been slowly moving their focus from agriculture to wildlife conservation.

To get to the fort, you'll turn at an Irving Oil gas station/restaurant complex called the Aulac Big Stop. Don't miss the display on the lawn of three, six-foot-tall sandpipers made from logs by chainsaw carver Monty MacMillan and placed here in 2016. They're a salute to the small shorebirds that stop in the area to fuel up — get the connecton to a gas station? — for their migration from the Arctic to South America.

"When the sandpipers gather on our mudflats in flocks of up to a quarter million birds, they make quite a sight — especially when they fly tightly together, white wings flashing in the sun, creating the illusion of smoke over water," an interpretive panel explains.

The next time I visit this fort — and there will be a next time — I'll bring binoculars and devote more time to fully exploring the landscape.

Stop 2/3: Beaubassin National Historic Site and Fort Lawrence National Historic Site

A picnic shelter along a flower-filled path is the highlight of Beaubassin and Fort Lawrence National Historic Sites/Jennifer Bain

I drive over the provincial border and find this two-for-one site behind the Tourism Nova Scotia visitor information center in Amherst.

There are no staff here, and no entry fees. Two plaques by the parking lot flanking a Canadian flag set the scene for what Parks Canada calls “one special place, two important sites.”

Designated in 2005, Beaubassin was once a major Acadian settlement on the Chignecto Isthmus that played a pivotal role in the 17th and 18th century geopolitical struggle between the British and French empires. The Acadians peacefully co-existed with the Mi’kmaq at this junction of overland and portage routes until a long-simmering dispute between the British and the French erupted in 1750. The French and Mi’kmaq pre-emptively burned the village and fled.

Designated in 1923, Fort Lawrence lies within Beaubassin’s boundaries and was built by British troops for the defence of the Isthmus of Chignecto and abandoned in 1756 after the 1755 capture of Fort Beauséjour.

The grassy, flower-filled site itself is a short, looped trail full of interpretive signage with a picnic shelter, benches and sweeping views. The remnants of the village and fort are, in the words of Parks Canada, “beneath the surface,” meaning they can’t be seen.

Even a simple picnic shelter can increase the draw of a national historic site/Jennifer Bain

I read how archaeologists have found glass and ceramic artifacts and charred building remains, and traces of gardens, paths, roads and fences. They have catalogued the impacts of burning the village, plowing the fields and occupying the land.

I don’t see any Short-Eared Owls, Barn Swallows or Bobolinks, but read how Parks Canada is monitoring and conserving habitat here for these species at risk. Endangered Little Brown Bats and Northern Long-Eared Bats nest here.

There’s much to read on a pleasant stroll around the site, and I realize how much even a few interpretive panels can help make a site like this — called a "view park" by Parks Canada — come alive.

“This now peaceful landscape was once one of the most coveted places in Acadie,” one panel explains.

When a Parks Canada site isn't staffed, interpretive panels are a key way to convey the historical story/Jennifer Bain

The Beaubassin region provided the quickest route between what’s now Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Rivers linked by portages provided the Mi’kmaq travel and trade routes through the area, which soon became a valuable route for New France, linking Acadie to Quebec and Louisbourg.

“Chignecto was strategically important, as whoever controlled it, controlled travel through the region and beyond,” one sign explains.

There’s more, of course, but I’m happy to just absorb view of the largest salt marshes on the Atlantic coast that were transformed into farmland when the Acadians constructed dykes. Generations of farmers have maintained the dykelands that, according to Parks Canada “also provide wildlife habitat, research and enjoyment.”

I leave satisfied that I've developed a basic understanding of the site.

Stop 4: Fort Gaspareaux National Historic Site

A view of Fort Gaspareaux National Historic Site in New Brunswick/Jennifer Bain

Back in New Brunswick, the road trip ends with a whimper, not a bang, at another self-guided site with free admission. This one's considered an archaeological site.

When I pull into the empty parking lot at Fort Gaspareaux, I see it’s not much more than a small point of flat coastal land — just 1.23 hectares (3 acres) — protected by a sea wall beside a natural harbor off the Northumberland Strait. Still, I know there are archaeological traces of a French fort here along with nine graves of soldiers.

Designated a national historic site in 1920, Fort Gaspareaux (known for a spell as Fort Monckton when it fell to the British) was a key spot in the struggle between France and Britain for North America in the 1750s. The fort was a border outpost built by French troops in 1751 by order of the governor-general of New France to prevent the British from penetrating the Isthmus of Chignecto. It also served as a provisioning base for the forts of Acadia during the French regime.

What's left of nine graves of Fort Gaspareaux soldiers/Jennifer Bain

On June 17, 1755, the fort was staffed by just 19 soldiers led by M. De Villeray when it was attacked by British soldiers under Colonel John Winslow and forced to surrender. The British burned the low-value fortress the next year and the site languished as farmland until Parks Canada took over.

I explore the grounds, hoping for more details. There are the remains of a ditch that must have protected the fort. A stone cairn has a plaque telling me what I’ve already read online. The lichen-covered gravestones are so old that the writing is no longer legible. I’ve read online that the men were killed by a Mi’kmaq militia while gathering wood in 1756, but have no way of verifying this or even learning their names.

I leave the fort full of questions, eager for the day when Parks Canada’s vision for the Chignecto Isthmus is finally realized and I can get answers.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places