Parks Canada's Athena George stands just above the spot where Moby Doll was harpooned in 1964, and holds archival photos of the killer whale/Jennifer Bain

Standing on the windswept eastern edge of Saturna Island, we paused for a few sombre moments to remember Moby Doll, the killer whale who changed the world.

Nearly 60 years ago, the Vancouver Aquarium wanted to create a life-size sculpture of a killer whale to hang in its lobby so it hired a team of hunters with harpoon guns to kill one that could be dissected, studied and measured for accurate dimensions.

“You see that lumpy rock?” asked Parks Canada’s Athena George, a summer interpreter for Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, pointing down to sea level from where we were standing on a bluff at East Point. “They mounted a harpoon right there.”

That was in May 1964. The hunters waited for a pod of orcas to swim by in the ocean between Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia and finally heard the telltale splashes on July 16. They shot the harpoon and hit a young whale.

A killer whale tooth is shown by Parks Canada's Athena George, who uses it when she does interpretation for visitors/Jennifer Bain

The whale didn’t die, though, and calmed down. The perplexed hunters were ordered to tow it to a makeshift ocean pen in Vancouver while the aquarium figured out what to do. The whale quickly became a media sensation and was named through a radio contest.

People feared orcas back then and didn’t know much about them. They didn’t realize there were distinct populations in this area — Southern Resident Killer Whales that fed mainly on salmon and Transient Killer Whales that devoured warm-blooded mammals — and they don't interbreed. Moby Doll, they later realized, was a Southern Resident.

“More people went to see this little whale than went to see the Beatles that summer — 20,000,” said George. “What happened was it changed our attitudes because people realized it wasn’t a killer and that it was gentle and intelligent. But it also started that gold rush era where people came and captured a lot of southern residents to take to aquariums around the world. And the southern resident pod has never really recovered from the big hit in late 1960s and early 1970s.”

Moby Doll died after 87 days in captivity of a fungal disease in its lungs. Aquarium officials belatedly realized she was a he who should have been called Moby Dick.

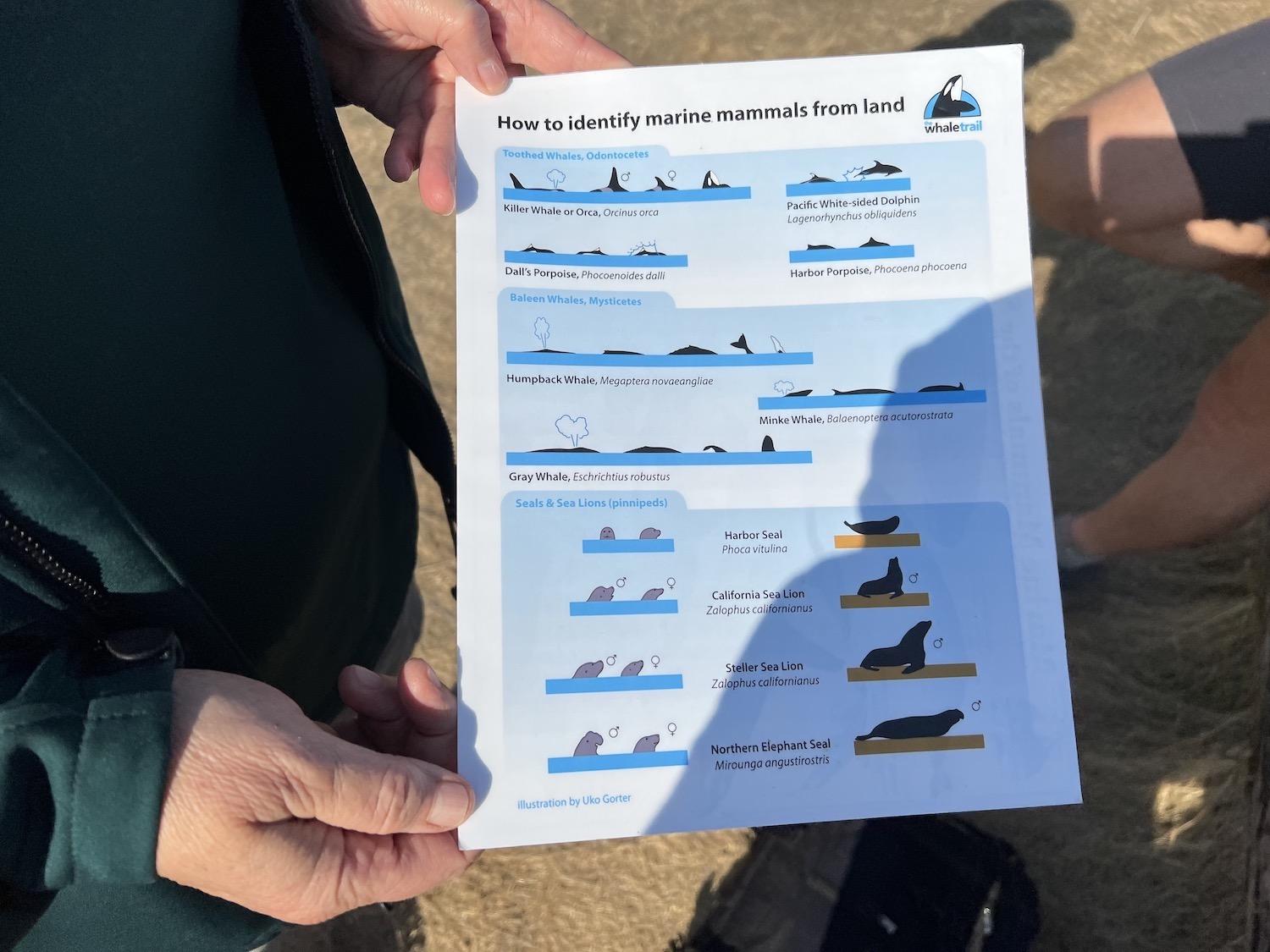

A Whale Trail guide to what to look for if you're on shore looking for whales and other marine mammals/Jennifer Bain

Moby Doll was the first of 55 orcas taken from these waters and sent to live in aquariums around the world.

“I tell this story mainly to talk about our shifting attitudes — it makes this place a little more special,” said George. There is nothing tangible to commerorate the harpoon site like a plaque, sculpture or interpretive sign. It's just a flat spot in the sandstone.

There are just 73 Southern Residents left and orcas have become an iconic symbol of coastal British Columbia.

George — who has worked here for 16 years — now promotes shore-based whale watching as an alternative to boat tours. “I call it whale waiting because you have to get into a different mindset. The mindset is you might not see whales and you have to stay a long time and you just have to get into the beauty of the place and enjoy the other things you might see along the way, like harbor porpoises, sea lions, humpback whales, gray whales and Transient killer whales.”

At East Point on Saturna Island, the iconic Fog Alarm Building stands behind a whale research platform/Jennifer Bain

Still, the question George gets asked more than anything is when can people see the whales. “And then I’m like `Oh they’re wild creatures. I don’t have a schedule for them. I tried calling them. They’re always late. So, I’ve been promoting whale waiting as a really lovely thing to do in our crazy life. COVID has been so stressful for everybody and so now people are coming to a place like this and just waiting. They’re just chilling. They’ll spend all day here. It’s mainly tourists.”

She warns people to expect “little tiny poofs of blow and tails and dorsal fins. You’re not going to see whales in space. Sometimes you get a breach. Sometimes you get a tail lift up.”

One point George likes to share is something she learned from Indigenous knowledge holder Tiffany Joseph. The W̱SÁNEĆ people call orcas ḴEL,ȽOLEMEĆEN, which means “mine that left the earth.” In the SENĆOŦEN language, ȽOL means "to go out far to sea" and ĆEN means "earth." When people think of being connected to orcas, and not just afraid of them, they are more likely to treat them with respect and love.

The "Welcome to Saturna Island" sign features a carving of an orca/Jennifer Bain

Established in 2003 to protect the Strait of Georgia Lowlands ecosystem, Gulf Islands is made up of 15 islands and 65 islets. There are no day use fees — just camping and mooring/docking fees for those who come by private boat.

“It’s a patchwork park because the park was formed out of bits and pieces that were still available over 15 or 16 large islands and lots of little islands,” said George. “It is fragmented and harder to understand it. You don’t just go to it. Boaters might be the ones that can access it the easiest because they can go puddling about from island to island and even the islands that don’t have ferries.”

Saturna Island is home to a feral goat herd. Two are shown on Mount Warbuton Pike/Jennifer Bain

On Saturna, for instance, Parks Canada quietly administers about half the land. You have to take one public ferry to get to it from the Swartz Bay terminal north of Victoria on Vancouver Island, and two to get back.

Before I went to East Point, I hiked with Rick Graham, one of Saturna’s 420 residents. He took me to Mount Warbuton Pike, the only place in Canada where the slender popcornflower (Plagiobothrys tenellus) grows. It wasn’t the right season for that but we did gaze down on farmland and spotted two of the island’s famous feral goats.

The popcornflower’s survival depends partly on these goats, who graze on competing plants and create open patches in the dirt for this rare species to grow. The goats have been immortalized in Milli Goat: A Kid on Saturna Island by Nancy Angermeyer, which is based on the true story of a dog that finds a feral, orphaned goat and brings it home.

At East Point, I met George by the East Point Lighthouse to look at the Moby Doll harpoon spot. I learned that for three years, when she's not doing summer interpretation, she works on the Southern Residents Killer Whale team developing visitor experiences for the Coastal B.C. Field Unit of Parks Canada. She has helped spots on Saturna, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve and Fort Rodd Hill and Fisgard Lighthouse National Historic Sites join the Whale Trail to promote land-based whale watching.

At the Saturna Heritage Centre in the Fog Alarm Building at East Point, volunteer administrator David Osborne shows a portion of Moby Doll's skull/Jennifer Bain

Then we walked over to the Fog Alarm Building (FAB), a 1936 light station that once held a fog horn that’s now the island's most photographed spot. Parks Canada planned to tear the asbestos-filled building down, but the community rallied to save and transform it into the Saturna Heritage Centre.

“We’re not really a museum and we don’t really have a collection per se,” volunteer administrator David Osborne told me. “Really what we are is a display and story space, and we’re trying to tell stories about Saturna and the Southern Gulf Islands.”

The center, which gets about 2,000 annual visitors between May and September, was given the upper part of Moby Doll’s skull a few years ago by the late director of the Vancouver Aquarium. Nobody knows where the rest of the orca's skeleton is, or what happened to its dissected brain.

“I think it’s great because in a way you could say Moby Doll has come home,” said Osborne.

Maureen Welton, vice-chair of the Saturna Island Marine Research and Education Society (SIMRES), stands by rocks with tafoni erosion patterns at East Point/Jennifer Bain

The last Saturna resident I met that day was Maureen Welton, vice-chair of the Saturna Island Marine Research and Education Society (SIMRES).

The community-based, non-profit group builds awareness about marine life and ecosystems in the Salish Sea. It has hydrophones at East Point positioned to listen to whales in Boundary Pass, the main shipping channel between the Pacific Ocean and Port of Vancouver, and a main throughway for the Southern Residents.

“We were all just really interested about learning more about what’s here because this is such an awesome place to watch whales and to see them, and for researchers to be positioned and see whales in the wild,” Welton explained.

East Point is special because dynamic currents create a nutrient-rich zone for whales, shorebirds, seals and sea lions. An undersea ridge deflects tidal currents to the surface, bringing nutrients up from the deep. Fresh water from rivers delivers more nutrients.

Parks Canada summer interpreter Athena George has been promoting land-based whale watching on Saturna Island for several years/Jennifer Bain

I only had two hours at East Point and didn’t spot any whales. I did hear about an old Parks Canada survey that asked people what they wanted to do when they visited the Gulf Islands.

“The top thing? Nothing. They wanted to do nothing,” said George. “They wanted to do whale waiting. They wanted to just read a book and relax and look at the water and chill. It’s hard as an interpreter when you’re trying to develop programs and the main thing visitors want is nothing.”

Another challenge is that Gulf Islands National Park Reserve doesn’t have a dedicated visitor center — just an operation center in the Vancouver Island town of Sidney.

Parks Canada's Ben Tooby, Molly Clarkson and Kirsten Mathison are shown on Russell Island in Gulf Islands National Park Reserve/Jennifer Bain

That’s where I met three Parks Canada staff to go island hopping and talk about three key projects. On Sidney Island, the SḰŦÁMEN QENÁȽ,ENEȻ SĆȺ (Taking Care of Sidney Island) project is restoring understory forest health. On Russell Island, sea gardens created by Coast Salish people are being restored. Rock walls at the low tide line make a bigger beach for clams and other critters to grow.

Gulf Islands, everyone agreed, isn’t a destination like Banff National Park, but part of the bigger picture of what you can do when exploring the Southern Salish Sea.

“Every Gulf Island has its own flavor,” said resource conservation manager Molly Clarkson. “A lot of people visit our park reserve and don’t know they’re in a park reserve.”

Molly Clarkson and Kirsten Mathison show one of the Parks Canada boats that's used in Gulf Islands National Park Reserve/Jennifer Bain

Our boat trip ends with some final insight into the Southern Resident whales.

Kirsten Mathison, acting resource management officer for the Southern Resident Killer Whale Marine Team, took us out by Pender Island to see an Interim Sanctuary Zone in effect between June 1 and Nov. 30 to protect the Southern Residents. Vessels and fishing are banned in these zones so people don’t interrupt the whales when they’re foraging and doing other social behaviors. Orcas fish and nurse less when boats are around, and the noise affects their echolocation.

When Parks Canada's Kirsten Mathison is out on the ocean doing whale research, she relies on binoculars with image stabilizers/Jennifer Bain

When Mathison is out for the day, she turns off her engines, depth sounders and radar “so we’re like a sitting silent duck in the water and won’t create any noise pollution.” She uses binoculars with image stabilizers and a super-zoom camera to record any whales, plus a hydrophone and baited underwater video camera.

“This gives us an idea of where they are in the park and their wellbeing and then we can record information about their behavior and what population we see,” she explained. “We’re trying to capture those identifying photos so back in office we can identify which groups are in the park and how they’re interacting.”

We look for whales, watching for telltale signs like blows in the distance, breaching, a collection of seabirds or a gathering of boats. But in the few minutes that we have, none magically appear on cue. Next time I visit the Gulf Islands, I'll do what George says and go "whale waiting" with a lawn chair, book and plenty of time.

While You’re Exploring The Gulf Islands:

The Latch Inn in Sidney is a quiet base if you plan to explore Gulf Islands National Park Reserve/Jennifer Bain

A great base to explore the Gulf Islands is Sidney, home to the summer walk-on passenger ferry to Sidney Spit and close to the passenger and vehicle ferries at the B.C. Ferries terminal at Swartz Bay. I stayed at the Latch Inn, which has six boutique rooms and includes a full, made-to-order breakfast. It dates back to 1925 when the lieutenant-governor of B.C. commissioned Canadian architect Samuel Maclure to build a summer home on forested property on the Saanich peninsula. The residence, completed in 1926 and dubbed Miraloma, once hosted garden parties and welcomed dignitaries and royalty. In the 1940s, it became known as "The Latch" because every door was opened with a latch and iron key. The newest owners took over in 2020 and did extensive upgrades.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Wish you would have at least pointed out that similar opportunities are available across the water in San Juan island national historical park. In fact, the park offers an extensive land based whale watching tour in the NPS app which makes finding whales accessible to far more people, most of whom don't get offered private boat rides by parcs Canada staff.

Thanks for the tip about San Juan Island - it would be great for its own story in 2023. To be clear, though, in my story I got to Saturna/East Point myself via a car ferry like everyone else. And you can do land-based whale watching in Greater Victoria at Fort Rodd Hill and Fisgard LIghthouse NHS (also mentioned in the story). For the last eight paragraphs of the story, I switch over to the private Parks Canada ride I got as a journalist to be out at sea with one of the whale researchers and to look briefly at a few other projects at Gulf Islands. In this part of BC, it's all about private boats but since I was only visiting, I was lucky that PC took me out.