It's not exactly the place where Hell bubbled up, but the vapor wafting from the crusty white soil and the heavy sulphuric odor are reminders that the volcano that created Valles Caldera 1.25 million years ago is not extinct, but rather in a deep, deep sleep.

"In the early 1900s, this was a sulfur mining operation. They mined out the sulfur rather quickly in a couple of years," David Krueger, the chief of interpretation of Valles Caldera National Preserve in northern New Mexico, explained as we carefully picked our way around the steaming landscape. "And then it's gone through various transformations, from being a health spa resort, which you see in some of the leftover buildings and effects on the landscape here."

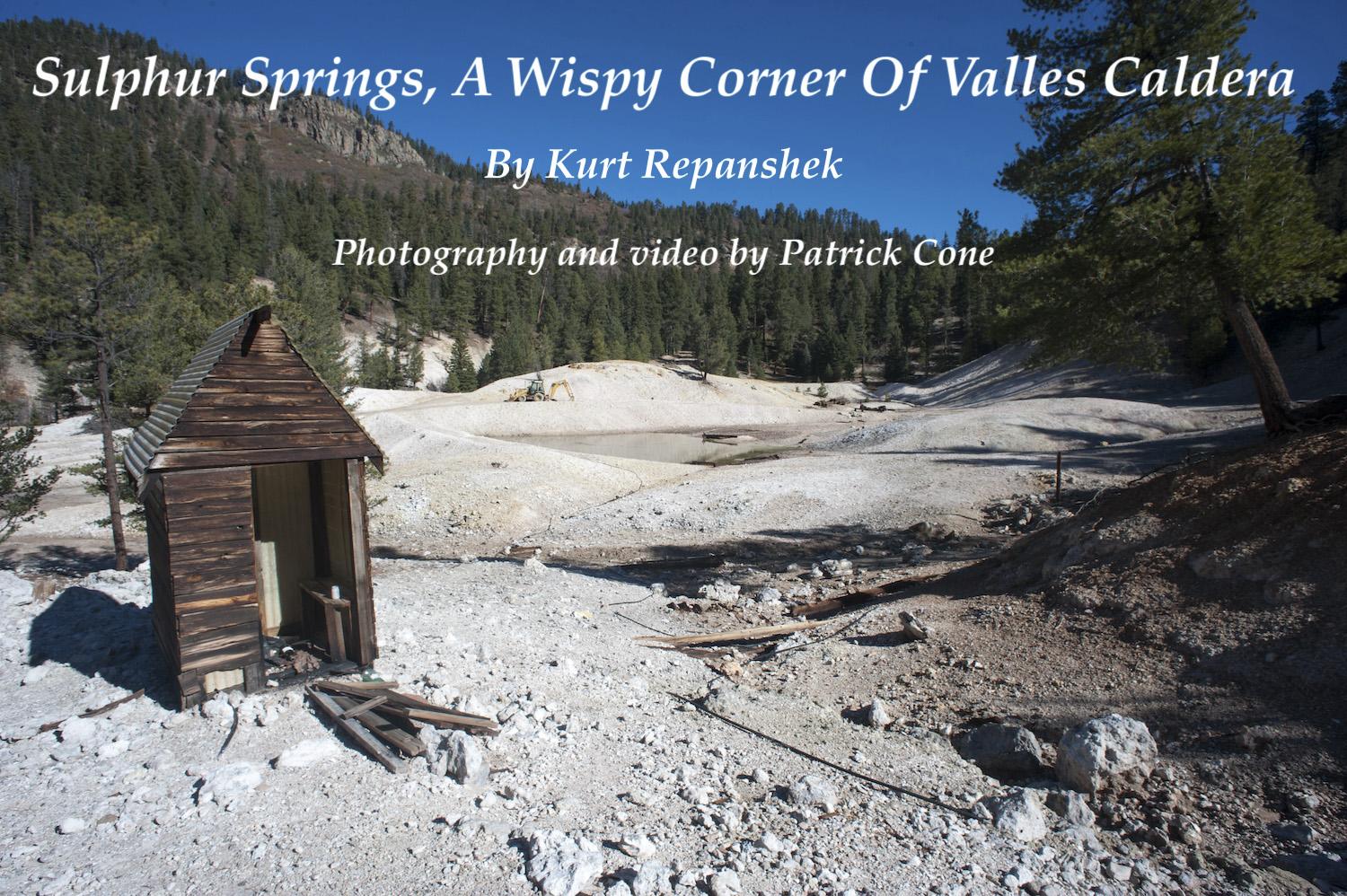

For $500,000 the 40 acres that surrounded us, a mash of historic bathhouses, collapsing structures, rusting cars, and holding ponds, came into the national preserve early in 2020. Despite its blighted appearance, this acreage known as Sulphur Springs in the preserve's southwestern corner is a geologic oddity.

The heavy forested mountains through which Sulphur Creek runs might belie to some the volatile, and geologically interersting, setting of this landscape. But the fame for the collection of hot and cold springs here dates to at least the 1500s when Spanish explorers trekked through the region, though native cultures surely knew of the area long before then. In 1900, Mariano S. Otero saw fortune in the sulphur brought to the surface by the hot waters and developed a millworks that sent sulphur by wagon to Santa Fe for shipment to eastern markets. The entreprenuer also saw tourist value in the springs, and developed a small resort with bathhouses and a hotel that continued operating until it burned down in the 1970s, according to the National Park Service.

Among the things the Park Service plans to remove from Sulphur Springs is this holding pond/Patrick Cone

In the 1980s, geologists from the nearby Los Alamos National Laboratory became interested in the hydrothermal resources here, and drilled exploratory wells as part of the agency's Continental Scientific Drilling Program.

"Drilling took place in August 1984 and quickly reached a depth of 2,809 feet," Craig Martin notes in his book, Valle Grande: A History Of The Baca Location No. 1. "The scientists collected data on the hydrothermal outflow plume of the geothermal area and on the nature of ring fractures. The new information greatly enhanced geologists' understanding of magma systems."

Drilling continued off and on until 1988, when the project ended after the geologists reached a depth of about 6,000 feet and temperatures of around 570° Fahrenheit, wrote Martin.

All that history shifted into Valles Caldera in 2020 when the National Park Service acquired Sulphur Springs thanks to the help of the National Parks Conservation Association, the National Park Trust, Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust, Cornell Douglas Foundation, an anonymous donor, and Mrs. Frances H. Kennedy, whose contribution was in honor of her late husband, former National Park Service Director Roger G. Kennedy.

Dotting the acquired landscape are seven named sulfuric acid springs known colorfully as Kidney and Stomach Trouble Spring, Footbath Spring, Ladies' Bathhouse Spring, Laxitive [sic] Spring, Turkey Spring, Lemonade Spring, and Electric Spring. No other sulfate-based acidic hot springs occur in the State of New Mexico, and they are rare throughout the rest of the United States, according to the Park Service.

This debris, possibly related to a bathhouse, surrounds a bubbling mud pot/Patrick Cone

As we wound our way across the bleached landscape, Krueger remind me of the volcanics below.

"We're still on a dormant volcano here in the middle of the Jemez Mountains," he pointed out. "And Sulphur Springs is where we actually have surficial geothermal features to show that there's still activity going on underneath. We've got pockets of fumaroles throughout here, we've got a couple of mud pots, and we've got cold and warm springs here as well. They're all very acidic. So pH can get down as low as 2 which is getting into a car battery acid range."

The Park Service intends to transform the landscape by removing the old wrecks and collapsing housing, draining the holding pond, and recontouring the landscape as much as possbile to its original appearance. The park has received funding to do the work, and currently is working on the environmental compliance with hopes to start the on-the-ground work next year. Once the debris has been removed and the recontouring completed, the park would like to build a boardwalk system through the area, complete with interpretive displays, said Krueger.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places