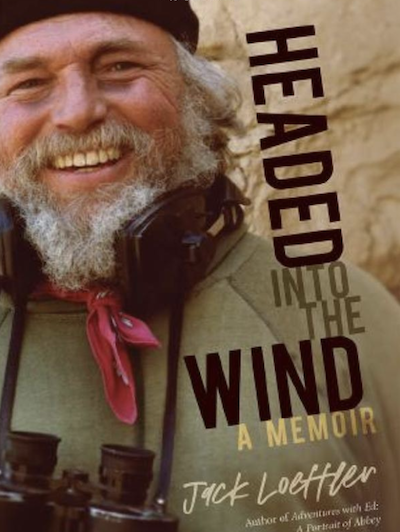

Years ago, when I was teaching a college course at Western Washington University titled “The American Literature of Nature and Place,” among the students’ favorites was writer Ed Abbey. Though I already knew Abbey’s work, I was always on the lookout for more insight into him and came across a book by Jack Loeffler titled Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Ed Abbey (2002), which I read, enjoyed, and from which I gained much insight into Abbey the man as well as the writer.

This book is not a biography, though it traces Abbey’s life, but an intimate portrayal of the man, and great storytelling about Jack Loeffler’s many interactions with his friend over the years. It is full of stories, anecdotes, even conversations, and I wondered how Loeffler could have recorded all the detail he put in this book.

Many years later I moved to New Mexico near Taos, attended the 50th anniversary celebration of the Wilderness Act in Albuquerque in 2014, and there was Jack Loeffler, among others, in a panel discussion about Abbey and a new film about him titled Wrenched from the Land, which later became a book of the same title edited by the filmmaker, ML Lincoln and her colleague publisher Diane Rapaport (2020).

I began to see Jack Loeffler’s presence everywhere in books, on television, and even on stage at the Lensic Performing Arts Center in Santa Fe setting up to record concerts by Santa Fe Pro Musica. He has a large presence down here, I asked myself. Who is this guy?

Jack likes to say he hasn’t had a career, he’s had a life, and Headed into the Wind explains what he means by this. In his life he has been an environmental activist, jazz musician, aural historian, museum curator, radio producer, sound collage artist, and has written eight books.

Now I understand how he collected the detail he put into Adventures with Ed — he has a great memory, takes good notes, is highly organized, and is adept with a tape recorder, not that he used the latter in gathering material on his adventures with Ed. He does quote from recorded interviews he did with him, but they were sit-down sessions where Jack posed questions and Abbey responded.

Over his long life (he is 86 this year, and going strong), Jack has consorted with many fascinating people we of environmental persuasion might recognize: Ed Abbey, of course, Dave Foreman, Stewart Brand, Stewart and Lee Udall, poets Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, David Brower, William deBuys, historian Bill Brown, and others. But there are many others encountered in his decades of aural history work to document Indigenous Southwest and Hispano music and culture whom we might not recognize but should know: Hopis John Lansa, Thomas Banyacya, and David Monongye; Navaho Shonto Begay; Hispanos Enrique Lara, Enrique Lamadrid, Cipriano Vigil, and E.A. “Tony” Mares, among many others.

Over the years, Jack “visited and sometimes lived with people from Navaho, Hopi, Huichol, Tarahumara, Seri, Mayan, Tohono Óodham, Pima, Yaqui, Ute, Jicarilla Apache, Chiricahua Apache, Nez Perce, Warm Spring Apache, Tewa Puebloan, Keresan Puebloan, and peoples from the California Indian Tribes, as well as Hispano, Basque, and rural Anglo traditional cultures.” What a wealth of experience, insight, and story a unique life has provided this astute and thoughtful observer. From long experience he takes the following,

In my experience these people of the land have a great diversity of cultural perspective, but they all share a common understanding about the nature of homeland. And that is, homeland requires that we ensure that if we are to be sustained by homeland we must reciprocally attend to the needs of homeland. Thus, I am a grassroots environmentalist who accepts that the human species is a part of the flow of Nature and that wilderness once included our species as part of its flow until we became so technologically adept and materialistically motivated that we exceeded the carrying capacity of too many ecosystems. Fortunately, some of our forebears realized that we must set aside wilderness areas as preserves into which we may not encroach so that these wilderness areas may maintain their biotic integrity.

Jack has explored the Southwest landscape and come to see it as “an integrated biogeographical system” in which Indigenous people “developed profound spiritual relationships with their homelands.” Avowing that he is not a religious man in the conventional sense, he has come to a recognition “of the sacred within the flow of Nature,” and this book explains how he got there.

Headed into the Wind is not all profound revelations, but is an entertaining and enjoyable read. Jack is a great storyteller and has many stories to tell. For instance, in an early chapter titled “An Epiphany” he describes how he was a trumpeter in the 433rd Army Band and one hot night the band was called out to the Nevada Proving Grounds and was playing military marches. “Then, halfway through ‘The Stars and Stripes Forever,’ the sky burst into light brighter than the sun, and an enormous mushroom cloud rocketed skyward, unfurling an array of colors, some of which do not otherwise appear in Nature in my experience.” This was a “defining moment” for him and he was “snapped into a far greater spectrum of consciousness than at any previous time, and thus I have remained.”

For the rest of his life, Jack explored this consciousness, and describes that journey.

Then there was the time he was invited by Stewart Brand to join a project Brand called America Needs Indians, which eventually led him and his wife Jean to live in a “forked stick hogan” on Navaho Mountain. As time passed, they were accepted by their Navaho hosts, and in one episode he was called upon to transport an ill elderly Navaho to the infirmary, no small journey in this rough country. He learned that his charge was 106 years old and “as a child had hidden with her family and livestock in nearby Paiute Canyon to avoid being rounded up by US troops under the command of Kit Carson to be marched off to Bosque Redondo near Fort Sumner hundreds of miles to the east.”

I was stunned by this. As I picked up the old lady to carry her back to the truck, I realized that I was carrying 106 years of living Navaho history in my arms. This woman had witnessed the early days of Manifest Destiny, when a youthful nation – the United States of America – had deemed itself worthy of the God-given right to spread across the continent, claiming every inch of the land thus eradicating every native culture that stood in its path.

Such experiences led him to his years of work on helping to protect and record what he could of native and Hispano cultures.

Then there were three years as a fire lookout in the Carson National Forest in the Jicarilla Ranger District, on Mesteños Mesa in northern New Mexico, and Jack shares some good stories about that episode, including when he got three vehicles stuck in quicksand in the middle of Bancos Arroyo, including a U.S. Forest Service jeep. As he and wife Jean contemplated how to get out of the predicament, they heard a low rumble, and a motorcycle gang, eight guys on Harleys, appeared, far from anywhere you would expect to see them.

“They stopped and looked at the slowly sinking vehicles. Then they looked at me. At first no one said a word, and then they all burst out laughing. Then I started to laugh with them. Soon we were all rolling around in the dirt, laughing uncontrollably.”

They helped him get the vehicles unstuck.

“We all sat around in the grass, smoked, and discussed the odds of getting three vehicles stuck in quicksand and then a motorcycle gang showing up at the crucial moment and saving my sorry ass. I was beholden to these guys who were the Blanco Bandits, apparently affiliated with the Hells Angels.”

One member of the gang was from a nearby Hispano village that was being flooded by a reservoir, and later Jack, beholden as he was, rescued one of their members whose machine broke down. That’s another great story, and there are many more.

Jack Loeffler was also an environmental activist, and he pulls some great stories from that part of his life. He co-founded the Central Clearing House, “a Santa Fe-based gang of environmental activists funded by a generous grant from Harvey Mudd.” With two others he founded the Black Mesa Defense Fund to fight the proposed mining of Black Mesa to provide coal to the massive Mohave Generating Station. The coal would be made into slurry and pumped 273 miles to the power plant, tapping into the precious water supply of the Hopi Independent Nation. This was a true David and Goliath battle, and the defenders lost, but stories here are well worth knowing. His managing to get Hopi Elders to the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972 is an especially good one.

Headed into the Wind is an inspiring read. Jack Loeffler has forged his own unique path through a long, fulfilling, and significant life. His contributions are many. He’s lost his share of battles, but he is upbeat. He writes, “As I reflect on the decades through which I’ve wended my way from being a young ‘know-it-all’ whippersnapper to an endlessly perturbed old fart, I ardently look for a state of balance between the two extremes.” He continues, “I have great faith in the young to discern what is worth knowing, which includes deep perspective born of cultural diversity within the context of biodiversity that will help shape the nature of the quest for wise-use technology.” He is convinced human consciousness must evolve, and does not know how that might happen, but he has spent sixty years doing his part to advance the process.

Loeffler closes with a flourish.

Consciousness is Nature’s enormous gift to our species as we have evolved over scores of millennia. How we use this gift of consciousness will determine how our role either develops or decays over the coming decades. Reveling in the flow of Nature leads to a level of spiritual awareness available nowhere else. Fully engaging the five bodily senses in wild lands is to reawaken lost sensibilities and redefine perspective. Looking deep into the heart of our galaxy of a summer nighttime while listening to coyotes sing allows a glimpse into just how profound this gift of consciousness is…. In consciousness we trust.

A “defining moment” for me, nowhere near as dramatic as that Jack experienced at Nevada Proving grounds, was when I realized that we humans have the gift and the burden of being evolution conscious of itself. Jack reminds me in this book that what we do with this gift will make all the difference for our future and for all living things with whom we share Earth.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places