Study: States And NPS Need To Reach Cooperative Goals On Wolves

By Kurt Repanshek

Squeezed hard against the northern boundary of Yellowstone National Park by a handful of the park's other wolf packs, the Phantom Lake pack naturally would head north into Montana on its hunts, but last winter the predators loped into a death trap.

Hunters anxious to add a gray wolf to their trophy list killed roughly half of the pack's 13 members, including what was believed to be the lead, or alpha, female, which often is the "glue" that holds a pack together.

"One of the first wolves that they had harvested out of the pack was, we think, the lead female," said Kira Cassidy, a park wildlife biologist. "They lost the lead, they lost five other pack members. Six out of the 13 that we knew about had been harvested. We only ever saw the alpha male on camera by himself. He just became a lone wolf. So that pack had dissolved."

Before Montana closed its wolf 2021-2022 hunting season, 19 Yellowstone wolves had been killed in the state, a controversial "harvest" that drew national attention over the loss of so many park wolves. Another four were killed by hunters in Wyoming, and two in Idaho. The 25 wolves lost to hunting represented 19 percent of the park's wolf population, according to Cassidy.

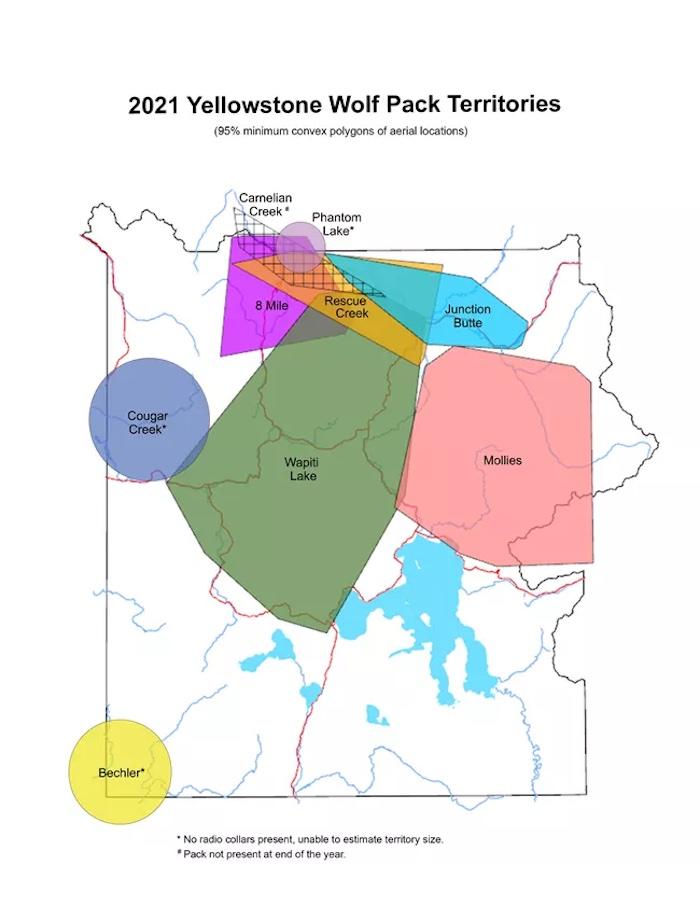

Pressure from surrounding wolf packs contributed to the Phantom Lake pack's wanderings outside of Yellowstone and into Montana/NPS map

While Yellowstone's wolf numbers rebounded by the end of 2022, when there were 108 wolves in ten packs, the greater impact of last winter's hunting season was the loss of the Phantom Lake pack and the near-loss of the 8-Mile pack, which lost its alpha female to hunters along with two other pack members.

"They all of a sudden were less competitive, they couldn't really hold their territory very well, they really struggled all winter," Cassidy, who collaborated with other wildlife biologists in Denali, Grand Teton and Voyageurs national parks, as well as Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, to assess how hunting impacts the dynamics of wolf packs, recalled of the 8-Mile pack.

A third pack that lost a good number of animals to hunting was the Junction Butte pack, though it managed to overcome the losses.

"They started the (2021-2022) hunting season with 28 members. They actually lost eight. A quarter of the pack or so," Cassidy said. "But the pack was able to recover. They ended up having four litters this year, which is somewhat common for them. They're back up to 25 wolves this year."

The pack benefitted not only but its sheer size, but also due to the fact that neither the alpha female or alpha male were killed.

"The study did show that large packs are pretty resilient," said the biologist. "Packs of 10 or more, even if they lose a couple of pack members to human causes, the chances that they persist are still very, very high. And so the Junction Butte pack is doing fine, back up at large pack size."

What the scientists concluded, was that "even the loss of a single wolf, especially a leader, can have detrimental effects on the pack. ... human impacts at the pack level are of concern to agencies and organizations with goals of natural regulation and preservation of biological processes."

"The human-caused mortality of any wolf decreased the predicted odds of pack persistence to the end of the biological year by 27% and reproduction the following year by 22% . The human-caused mortality of a pack leader decreased the predicted odds of pack persistence to the end of the biological year by 73% and reproduction the following year by 49%. These results indicate that human activities can have major negative effects on the biological processes of wildlife that use protected areas." -- Human-caused mortality triggers pack instability in gray wolves, in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Need For Interagency Cooperation

"What this science from this distinguished group of scientists offers is a critical message to both park staff and neighboring states — that collaboration is critical," said Elaine Leslie, the National Park Service's chief of biological resources when she retired at the end of 2019. "Hunting pressure on highly social species such as wolves can result in the decimation of pack as we have witnessed. ...and it can result in reduced diversity in DNA from a genetics perspective.

"It can be difficult for both federal agencies and states to come together and find consensus on these highly charged issues," added Leslie, who wasn't involved in the study. "But personnel have to keep talking even with differing missions. The American public has spoken and put their money behind it: the wildlife restored and protected in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and elsewhere is an important contribution to our national natural heritage and must be sustained."

By the end of last winter's wolf hunt, Yellowstone Superintendent Cam Sholly was able to work with Montana officials going forward to limit the number of wolves that could be taken in areas along the park's boundary.

That state's hunt, and wolf hunts in the other parks contributing to the paper, demonstrates how human-caused mortalities can disrupt individual packs, said Cassidy.

The study, which appeared in the January 17 edition of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (attached below), followed by a handful of years a wolf study in Yukon-Charley Rivers that was forced to end in 2016 because the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had sponsored a predator control program that had killed at least 90 wolves that had home ranges within the national preserve.

As a result of state shoot-on-sight and other lethal removal tactics, NPS concludes that the wolf population in the 2.5-million-acre national preserve is “no longer in a natural state” nor are there enough survivors to maintain a “self-sustaining population," Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility said in a release at the time.

Cassidy's research didn't build on that Yukon-Charley Rivers study, which examined how the national preserve's overall wolf population was affected by hunting outside the preserve, but rather drilled down into the hunting impacts on individual packs.

"We wanted to focus on this scale that was separate from the population, because you can have population numbers year after year that look very similar and endure quite a lot of human-caused mortality," she said. "But that's a separate scale from the pack level, where you might have quite a lot of social dynamics changing due to human-caused mortality and very little change to the population level. And so part of the point of the study was to show that both scales are important to consider when we're thinking about wolves."

The study drew the attention of Erik Molvar, a wildlife biologist and executive director with Western Watersheds Project, who blamed special interests for driving the wolf hunts.

“Clearly, the National Park Service is unable to protect wolves living inside national parks from depredations that occur from wolf hunters and wildlife-killing agencies outside their borders,” said Molvar in a release. “Excessively permissive hunting and trapping policies by anti-wolf state governments, and federal and state agencies eager to kill wolves to appease the livestock industry and soothe irrational and unfounded fears of rural local residents, are to blame.”

Yellowstone's Wolf Recovery

Long viewed as a voracious predator best left dead, wolves had been extirpated from Yellowstone by the mid-20th century. The park's last known pack was wiped out in 1926, though there were occasional reports of lone wolves roaming the park years later. But the removal of the canine eventually came to be viewed as a mistake, for it was an apex predator that benefited other species in the park, whether by serving as a population control on elk, for example, or by leaving behind kills that nourished other species.

"In the 1960s, NPS wildlife management policy changed to allow populations to manage themselves. Many suggested at the time that for such regulation to succeed, the wolf had to be a part of the picture," notes Yellowstone's website.

Nearly three decades ago, back in 1995, the dream of seeing wolves running wild in Yellowstone came to life, as the first of a handful or two of Canadian wolves were set free into the park under a government-led recovery program. It was the culmination of a long-fought effort to see Yellowstone's ecosystem become whole once again with its complete prey and predator base. And it also was the beginning of a new chapter in the park's wildlife history. In the ensuing 28 years, the wolf recovery program has succeeded far beyond expectations, both by repopulating the park with canis lupus, contributing to a reduction in the soaring population of the park's northern elk herd and, most unexpectedly, providing both researchers and park visitors with numerous glimpses of wolves.

It's also been a tourism bonanza, as "wolf watchers" stream into the park every year to see if they can spot one of the predators. Estimates have placed the economic impact of that draw to the states surrounding the park at $82.7 million a year.

While the recovery program has struggled at times -- wolf No. 10, the alpha male of the Rose Creek Pack that was among the first 14 wolves brought into Yellowstone in January 1995, was shot and killed, states surrounding the park have put wolf recovery in jeopardy with their hunting seasons, mange and distemper have swept through some of the park's packs -- it largely has been an overwhelming success.

Need For An Interagency Wolf Plan?

Wildlife issues involving Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks have led to creation of an Interagecy Bison Management Plan and Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, and while the latest study on wolf mortality didn't specifically call for a similar interagency plan or committee, it did say "[L]imiting human-caused mortalities is possible if efforts are made toward cooperative interagency goals. Specifically, jurisdictions adjacent to parks could adjust hunting seasons and lethal control near parks to accommodate cross-boundary movements and stability of packs."

At Yellowstone, Superintendent Sholly said "[T]here is always a need for us to continue improving our transboundary coordination efforts. Not only when it comes to various wildlife species, but also other common challenges we all face within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, like climate impacts, invasive species, maintaining viable wildlife corridors, and increasing visitation impacts."

"This is a primary reason the states (Montana, Wyoming, Idahoa) are now part of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee, so we can ensure we have the right representation at the table on many of these very complex issues," he added. "Relative to wolves, our efforts last year working with the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Commission to get the [wolf hunting] quotas reinstated north of Yellowstone is a good example of recent cooperation with a result that wasn’t perfect for everyone but represented a compromise."

According to Western Watersheds, "Indigenous leaders have long called for wolf protections. In 2017, Protect the Wolves, an Indigenous-led wolf advocacy group, officially petitioned the state governments of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho to create a Sacred Resource Protection Zone to ban wolf hunting and trapping within 50 kilometers (31 miles) of Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

"The state governments should have listened to Indigenous voices and created this Sacred Resource Protection Zone around Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, to prevent the killing of national park wolves,” said Roger Dobson, a Cowlitz Tribal Member and director of Tribal Cultural Resources with Protect the Wolves. “In this new study, we now have definitive proof that the failure of state governments to protect wolves on the lands surrounding Yellowstone and Grand Teton are causing serious unnatural disruptions for wolf packs, and preventing these wolves from living out their lives in a natural and undisturbed way.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places