Conifer forests in lower elevation riparian areas of Kings Canyon (above), Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks are becoming "stranded" by climate change, according to a new study/Patrick Cone file

Iconic forests that stretch across Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks are beginning to fray at the edges as the warming climate is creating unsuitable growing conditions for them, according to a study led by Stanford University researchers.

While stands of ponderosa pine, sugar pine, and Douglas fir found in the lower elevations of those parks might be able to tolerate the change in the short run, they more than likely will eventually be replaced by other species suited to a warmer climate if current trends continue, the researchers predict.

Computer simulations run by the researchers pointed out that "the mean elevation of conifers has shifted 34 meters, or almost 112 feet, upslope since the 1930s, while the temperatures most suitable for conifers have outclimbed the trees, shifting 182 meters, or nearly 600 feet, upslope on average. In other words, the speed of change has outpaced the ability of many conifers to adapt or shift their range, making them highly vulnerable to replacement, especially after stand-clearing wildfires."

“Forest and fire managers need to know where their limited resources can have the most impact,” said study lead author Avery Hill, a graduate student in biology at Stanford’s School of Humanities & Sciences at the time of the research, which was published Tuesday in PNAS Nexus. “This study provides a strong foundation for understanding where forest transitions are likely to occur, and how that will affect future ecosystem processes like wildfire regimes.”

Hill and his co-researchers came to their conclusions by combing through nine decades of vegetation data, when the vast majority of human-caused warming had yet to occur.

"The study estimates that about 20 percent of all Sierra Nevada conifers are mismatched with the climate around them," said a release pointing to the study. "Most of those mismatched trees are found below an elevation of 2,356 meters, or 7,730 feet. The prognosis: even if global heat-trapping pollution decreases to the low end of scientific projections, the number of Sierra Nevada conifers no longer suited to the climate will double within the next 77 years."

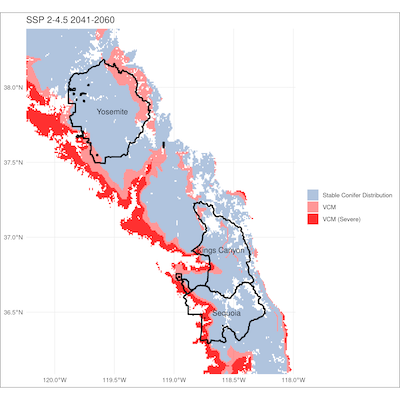

Vegetative stranding could creep further into Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks if expected trends fall into place. This map shows the potential encroachment for the years 2041-2060/Avery Hill

While maps associated with the study lack ground-level details, Hill said in an email that "there is indeed a little overlap in each of those national parks, particularly along [lower elevation] riparian areas."

The impact of the warming climate on forests "will require more adaptive wildfire management that eschews suppression and resistance to change for the opportunity to direct forest transitions for the benefit of ecosystems and nearby communities," the release said. "Similarly, conservation and post-fire reforestation efforts will need to consider how to ensure forests are in equilibrium with future conditions, according to the researchers. Should a burned forest be replanted with species new to the area? Should habitats that are predicted to go out of equilibrium with an area’s climate be burned proactively to reduce the risk of catastrophic blazes and corresponding vegetation conversion?"

“Our maps force some critical – and difficult – conversations about how to manage impending ecological transitions,” said Hill. “These conversations can lead to better outcomes for ecosystems and people.”

What the study did not address was the overall impact of changes in the forests to wildlife, birds, and understory vegetation.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places