For thousands of years Quitobaquito Springs has quenched the thirst of travelers/Eric Jay Toll

Tracing The Ancient Salt Trails Through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

By Eric Jay Toll

It was a well-trekked sandy trail leading us into the thick brush. A gentle breeze rustled the shrubs and straggling mesquite and ironwood trees. In an instant on the short track, we seemed to leave the Sonoran Desert behind and move into a stunted but lush preserve.

Two of us were camping for a long weekend at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, along the Arizona-Sonora, Mexico border at Lukeville, intent on exploring areas we had not previously visited before the hot summer set in. In the middle of one of the four largest North American deserts, we were walking into an honest-to-God oasis, just without the Sahara palm trees. The idea that a small pond or lake had water in it year-round was too much of an attraction.

With each step we realized that we were following in the path of ancestors of the Tohono O’odham Indian Nation. For perhaps thousands of years, these people trekked from their pueblos across this region to the massive salt flat, el salinas, on the Golfo de Santa Clara at the north end of the Gulf of California.

The ceremonial journeys vanished as nations formed, borders were established, and modern times made salt more available. But in 2015, José Mariá and María Garcia, a tribal healer of the O’odham Nation, were involved in a rebirth of the Old Salt Trails as a rite of passage for today’s O’odhams.

“For 150 years, we did not celebrate the (pilgrimage for the salt trail),” explained Mariá, who said the sea is part of the tribe’s cultural identity and was viewed as a god. “We used to go to the sea and ask him to bring rain to the desert.”

He said that bringing back the salt is “proof of a feat.”

In March 2015, Mariá and Garcia set out from the Tohono O’odham Nation, centered at Sells, Arizona, just east of the national monument, to retrace the pilgrimage. A second quest took place in 2016. “My main intention is to rebuild the path from Gila Bend to the sea,” Maria said. “The pilgrimage is not for everyone. Now we have bad physical conditions, and we are weak. They used to go at age 14; now it’s 16.”

Though the two wanted to continue the annual treks as a rite of passage for the modern O’odham, illness forced an indeterminate pause.

The routes, the ancient ones and those retraced in 2015 and 2016, passed from the O’odham Nation and through today’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The recent ones were parallel to different ancient salt trails but only crossed those in several locations on the way to Ojos de Agua Dulce, the salt and freshwater wetlands in the salinas where the mineral is gathered, and skirting the Bahia Adair, on the edge of Gulfo de Santa Clara and the salinas.

The ceremonial journey averaged about 26 miles each day. It took two days to pass from the O’odham lands across Organ Pipe Cactus and into México. The journey took nine days to traverse the entire 237-mile roundtrip. Only one day for rest, recovery, and resupply was scheduled at Camp O’Odham in México.

On the walk, the men prayed. The salt was sometimes loaded on horses in netted bags because of its water content and weight.

A Desert Oasis

As we loosely followed the salt trail, the path turned slightly, and the oasis came into view. Quitobaquito, a small lake fed by several springs and winter runoff and whose name given by the Papago Indians means "house ring spring," is an incongruous part of the Sonoran Desert. According to archaeologists, the oasis held an essential role in the lives of people living and crossing the area possibly 16,000 years ago. Today it sits almost on the international boundary between the two countries where the national monument meets its cross-border sister national park, Reserva Biosfera Pinacate y Gran Disierto de Altar.

“Paleoindian artifacts have not been found within the boundaries of the monument but have been documented as close as Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and at archaeological sites in southeast Arizona and northern Sonora,” said Jessica Pope, Organ Pipe Cactus’s interim superintendent, in an email. “Artifacts have also been found at archaeological sites in southeast Arizona and northern Sonora. Organ Pipe contains many different archaeological sites spanning human history from at least the Archaic period …through the Ceramic period…The monument includes a vast array of human history, and the site types are very diverse and range from temporary, to seasonal, to permanent use over the course of thousands of years.”

Standing at the edge of Quitobaquito’s shallow half-acre pool of crystal-clear water, we watched ducks cruise the surface, scarfing bugs. Our eyes followed the movements of Quitobaquito pupfish, a roughly inch-long federally protected species with chubby silver bodies. The oasis is one of the two places in North America where this species has been found; the other is across the border in specific places along the Sonoyta River. Another protected species, the endangered Sonoyta Mud Turtle, also lives here.

Trekkers across Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument would move from water source to water source in the Sonoran Desert. Dripping Springs is one active source that is an easy hike for those wanting to see a desert spring. Filter the water before drinking/Eric Jay Toll

The oasis has been in use for possibly 16,000 years before present-day Arizona, and more recent ancestral inhabitants left remnants of their lives nearby that were discovered by archaeologists in the early 1950s. The pot shards, obsidian chips from tools and weapons, and other community discards in middens—communal trash heaps—were collected and moved from the sites for study. Today’s archaeologists leave finds in situ to help better understand the context of materials use and community life.

Quitobaquito is the most accessible oasis on the monument. There are several springs nearby that hikers can visit. We followed the trickling flow from the lake to a second spring, about a tenth-of-a-mile north of the oasis. The water bubbled up from the ground to form a puddle-size pool that overflowed down the shallow wash to Quitobaquito.

From Quitobaquito, we embarked on the long tour of historic, geologic, and archaeological sites along Puerto Blanco Drive that loops through the southern half of the monument and decided to visit Dripping Springs. Pulling into a parking area off the one-way dirt-and-sometimes gravel road for the picnic area at the Red Tanks Trailhead, we headed across the desert plain towards Puerto Blanco Pass. Our route followed a minor dip in the landscape that serves as the drainage from Dripping Springs. Just under a half-mile hike, the ground rose quickly, and the trail simply ended. Pushing through the thick brush, we found ourselves at the foot of the springs. Water dripped as a shadow down the face of the layered rock and into the drainage course.

Crossing Ancient Paths

It's very likely that our stop at the spring mirrored that of prehistoric travelers who crossed this dusty, arid landscape.

Those treks, however, had a great purpose. The ancestral people in the Sonoran Desert crossed the land to Gulfo de Santa Clara, at the north end of the Gulf of California, and harvested salt from the salinas, the salt plains adjoining the gulf. To get there, they passed from the Tohono O’odham Nation through what is now Organ Pipe Cactus and across the now Biosfera El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar to gather their salt.

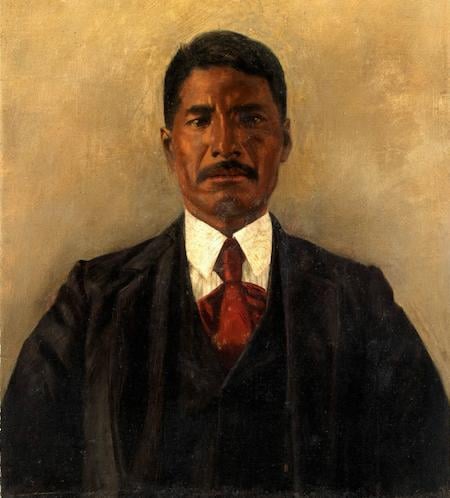

José Lewis twice trekked the salt trail in the 19th century/Smithsonian Institution

We know about the salt gathering, thanks in part to Alberto Tapia Landeros and Federico Godinez Leal of Autonomous University of Baja California. The two compiled a detailed report in 2017, “Pilgrimages for the Ancestral Walking Trails,” about the salinas, Gran Desierto de Altar, and the ancestral and cultural traditions associated with the quest for salt, or the theme, “go for the salt.” In their report, Landeros and Godinez cited a 1955 interview with José Lewis, a Papago tribal elder, who trekked the ancient salt trails in the late 19th century. The Papago are now known as the Tohono O’odham Indians.

“I have been (to the salinas) for the first time in 1879 and twice in 1885,” Lewis told Edward Spicer in that 1955 interview about ‘Going for the Salt,’ now archived at the Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives. “When a person does his first trip to the Gulf of Baja California to obtain salt, he suffers more than others who have been in ceremonies before. Very few can be the leaders to go for the salt. The leader must know the types of ceremonies to give and meet those who go with him. The people who go for salt have to leave all at home and must not think in nothing else when he leaves his house.”

Lewis, as referred to in the handwritten document held by the Smithsonian, said, “The leader has all who accompany him prepare within four days. After four days, they will leave their homes in the morning and travel 40 or 60 miles to camp.”

Exactly what route they traveled for the salt is impossible to say.

“It is likely that there was not one salt trail but many trails that served similar functions,” said Pope. Through history many traveled “from the desert interior Southwest to coast to obtain coastal and marine resources and to carry out culturally-specific activities—again over the course of perhaps thousands of years.”

The contemporary trails started near Sells and took different routes on the east and west sides of the Ajo Mountains. The precise route was never publicly disclosed. Pope and Mariá both referenced that there were possibly many salt trails, some of which may have also been used by the Spanish to explore the area. Both trails ended southeast of the village of Golfo de Santa Clara somewhere around Bahia Adair.

It’s a 10,000-year journey to experience in small ways in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Located off Arizona Route 85 at the U.S.-México border in Lukeville, the monument is about three hours from Tucson, five hours from Phoenix. The nearest lodging choices are in Ajo, a historic mining town about a half-hour north of the monument. There’s a motel in Why, a town named for the Y-intersections of Arizona 85 and 86. The monument has a beautifully served campground, Twin Peaks, with spaces separated for tents and RVs, flush toilets and showers, and a primitive campground, Alamo, with no reservations, RVs, water or lights, and just four campsites.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Nice report.

Any concerns about security, or signs of illegal activities?