Riel House National Historic Site depicts 1886 when Louis Riel's family is mourning his execution/Jennifer Bain

Métis leader Louis Riel, the Father of Manitoba, never actually lived in the white wooden house with forest green trim in Winnipeg that’s a national historic site bearing his name. But his mother did and, in a rather sombre twist, his body lay in state here for two days after he was hanged in 1885 for treason.

Framed photos show a bearded Riel looking like a dynamic statesman in his suit. Mirrors are covered with black cloths to signify that the Catholic family is in mourning. And when passionate young Métis interpreters show you around, they’ll open a closet in the living room that once stored the simple pine coffin that first held Riel’s body.

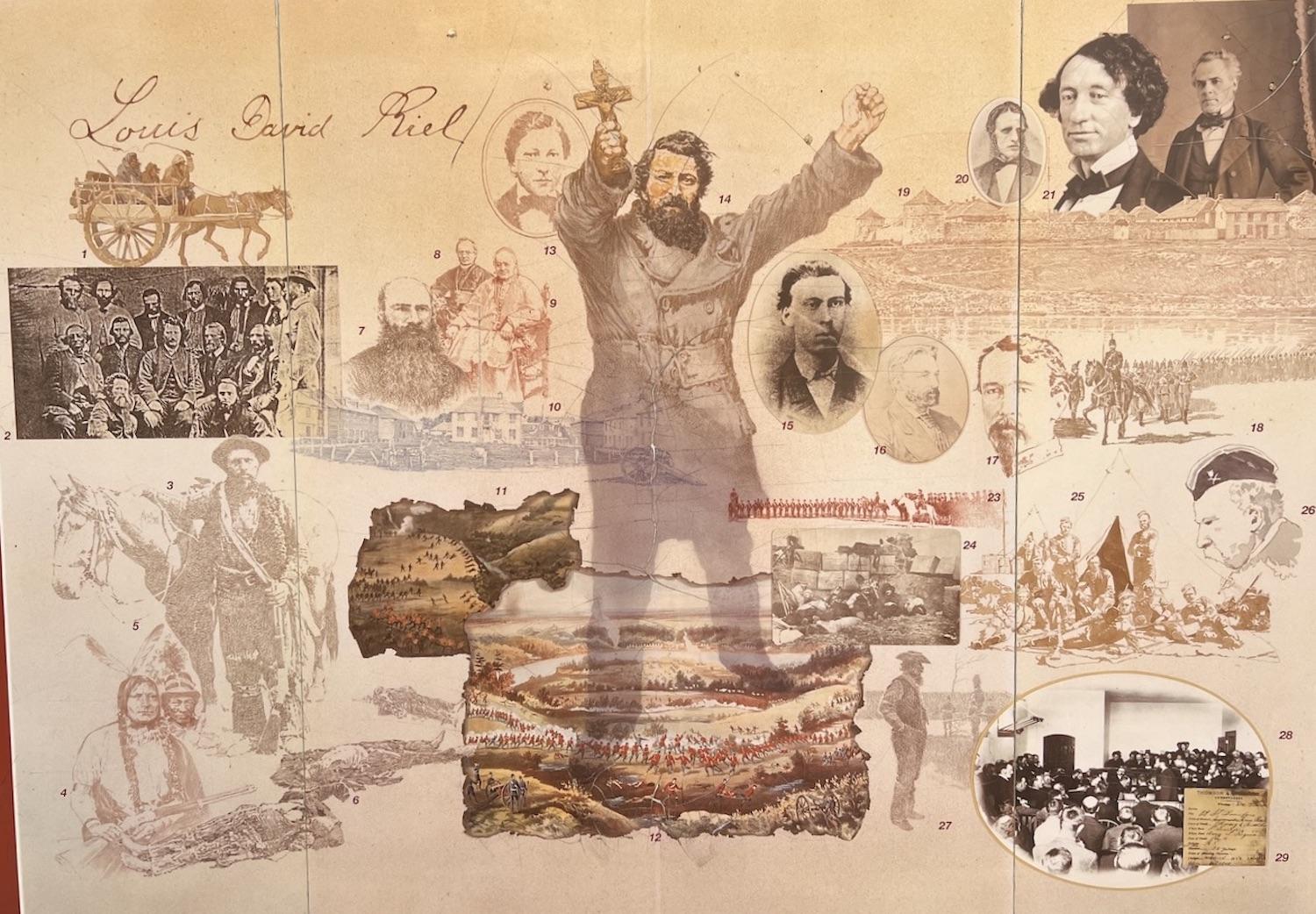

Riel was executed when he was just 41 after dedicating his short life to defending Métis and French-Canadian rights in the West during the turbulent years of 1869 to 1885 that gave birth to Manitoba. He was elected to Parliament three times but never allowed to take his seat.

Outdoor signs at Riel House National Historic Site bring Métis leader Louis Riel to life/Jennifer Bain

“He was a gifted poet and eloquent speaker and believed that he had a mission to bring peace and justice to his people,” reveal interpretive signs at Riel House National Historic Site. “Today, Riel remains a controversial figure to some Canadians. But for the Métis he is an enduring hero and constant inspiration.”

Riel House is the only heritage place in Canada where Riel is commemorated as a person of national historic significance. It represents the river lot system of the early settlers and explores 19th-century Red River Métis culture and daily life. Parks Canada opened the site in 1980 after restoring the farm home and furnishing it with more than 800 reproduced artifacts to reflect the spring of 1886 when Riel’s family was mourning his death.

The Métis — the children of First Nations women and French-Canadian voyageurs and other European fur traders — developed their own customary laws, a river lot landholding system and the Michif language that blended French and Cree. They protested 1816 restrictions on the sale of pemmican, a portable meal of dried bison or other meat pounded to a coarse powder and mixed with melted fat and berries. When rival fur trade companies (the North West Co. and Hudson’s Bay Co.) merged in 1821, the Métis continued to hunt and freight goods for the new company but also traded independently and eventually broke the trade monopoly.

At Riel House National Historic Site, interpreter Gabrielle LaPlume shows how Red River log construction worked/Jennifer Bain

The Manitoba Act that created the province in 1870 guaranteed the Métis ownership of the land they already occupied and reserved 1.4 million acres for their children. But settlers took much of the reserved land, forcing the Métis to migrate and resettle. They became impoverished and lost their central place in the society and economy of the new province. Riel led a series of battles that ended in Batoche, Saskatchewan in 1885 with his surrender.

Riel House was built around 1881 using a traditional French-Canadian construction style known as “post on sill” or “Red River frame” that combined squared logs for the timber frame structure and horizontal log infill. Spaces between the logs were filled or “chinked” with a clay and straw mud plaster. Inside and outside log walls were usually covered in whitewashed mud plaster. This house boasts the exterior board siding that became popular by the 1880s.

The river lot system allowed fair access to water and transportation.

Riel House National Historic staff wear period costumes from 1886 and beaded Métis moccasins/Jennifer Bain

Riel was born and raised in Saint-Boniface (now Winnipeg’s French Quarter) to miller/community leader Louis Riel Sr. and Julie Lagimodière. He was sent to Montreal to study priesthood and law as a teenager before returning when he was 24 to become a champion for his people.

Except for a brief visit in 1883, Riel never lived in Riel House. But he did live on this site in an earlier home where he hosted Métis council meetings. His wife Marguerite died in this house in 1886, and their children were cared for here by his mother and brother. The house was passed down through the family until Parks Canada took over in 1970.

The Louis Riel Institute, with Manitoba Métis Federation funding, works with Parks Canada to offer interpretive programming and Métis culture demonstrations to school groups in May and June, and to the public in July and August.

Riel House National Historic Site staff Nathan d'Eschambault, Maxine Lavitt and Gabrielle LaPlume/Jennifer Bain

Staff are always Métis, like Louis Riel Institute coordinator Maxine Lavitt and interpreters Gabrielle LaPlume and Nathan d’Eschambault. They tell me about farm life, churning butter, beading and finger weaving and explain the versatility of the colorful woven Métis sash.

“Beading was very important to the Métis — it was used very spiritually,” explains d’Eschambault. “We’re very spiritual people and we like to connect with community. One of the reasons the river lots were so skinny was to connect with neighbors because you’d be trading with your community.”

The house, once home to 12 members of the Riel’s extended family, boasts a peat moss stove, bison furs from communal hunts once used for trading, replica antiques and one actual lithograph sent by Riel’s devastated sister after his death.

Inside Riel House, Gabrielle LaPlume shows off a home that depicts 1886/Jennifer Bain

The mirrors and the portraits have been covered, explains LaPlume, because of Catholic protocols and superstitions. “Since Louis had passed they would have covered the mirrors out of respect and out of ghost tales that you would have been able to see the deceased behind you.” The typical mourning period of two years was doubled when Riel’s young wife died not long after him. A black cross sits on top of the house.

Riel House, a long 20 minutes from downtown Winnipeg, often gets overlooked by visitors.

It took more than a century for opinions to change, but many finally consider Riel to be the Father of Manitoba, making this the only province brought into Confederation by Indigenous leadership. In 1992, the House of Commons unanimously recognized Riel’s “unique and historic role as a founder of Manitoba and his contribution in the development of Confederation.” Métis singer Willie Dunn commemorated him in a famous song, "Louis Riel." Louis Riel Day, a provincial holiday, is celebrated on the third Monday of February.

The charred coffin that Louis Riel's body was first placed in is now at Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum. He was buried in a more elaborate coffin/Jennifer Bain

To follow the story through, stop by Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum to see the famous pine coffin plus pieces of the rope said to have been used to hang Riel.

When Riel was executed in Regina, Saskatchewan, his body was placed in a pine coffin for a private train ride back to Manitoba. His body was claimed by his brother, brought to the family home and transferred to a protective metal casket with a glass window so mourners could see his face. For two days people came to pay their respects as 50 armed Métis stood by to deter anyone who dared disturb the vigil. Finally, Riel was buried in an elaborate rosewood coffin.

The family filled the original pine coffin with photos and papers and stored it in the closet until donating it to the Societé historique de Saint-Boniface for display their museum within St. Boniface Cathedral. The coffin survived a 1968 fire that destroyed the cathedral before being transferred to the care of Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum.

A statue of an anguished and nude Louis Riel ignited controversy when first unveiled in Winnipeg. It was moved to the Université de Saint-Boniface/Jennifer Bain

The museum is steps from Riel’s grave in Saint-Boniface Cemetery and a block from a controversial statue on the Université de Saint-Boniface campus that shows a naked and anguished Riel. Etched into the monument is something Riel famously said just months before his death: “I know that through the grace of God I am the founder of Manitoba.”

From Saint-Boniface, walk over the Esplanade Riel pedestrian bridge to the 62.5-acre Forks National Historic Site. Co-owned and operated by Parks Canada, the Forks North Portage Partnership and the Canadian Museum For Human Rights, the Forks is at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers and has been a meeting place for more than 6,000 years.

More than four million visitors a year come to a hotel, children’s theater and festival park/stage. They eat and shop at the Forks Market, home to Manitobah Mukluks. They learn about treaties at the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba’s Agowiidiwinan Centre. Just past the Oodena Celebration Circle, they explore the South Point area that has been named Niizhoziibean to honor the city’s Indigenous heritage and its prominent place alongside these two rivers.

On a guided tour of the Forks National Historic Site, Ayden Schumacher shows off a beaver pelt that was so critical to the fur trade/Jennifer Bain

Parks Canada operates a small portion of the Forks. The 8.9-acre green space dominated by Fort Parka (a children’s playground and splash pad), a stretch of the riverwalk and a field full of charming but also reviled and gopher-like Richardson’s ground squirrels.

On a guided summer tour called “Where Our Stories Meet,” interpretations coordinator Ayden Schumacher recounts the history of the First Nations people who traded at the Forks for thousands of years before European explorers arrived, and delves into how the Métis shaped the land that would become Manitoba. The tour ends as we gaze across the river to Saint-Boniface and talk once again about how Louis Riel sacrificed his life in his fight to protect Métis rights and culture.

Explore Indigenous Winnipeg:

At Qaumajuq, Indigenous initiatives coordinator Nikki Schuweiler stands in front of the visible vault full of Inuit art/Jennifer Bain

• In Canada, “Indigenous” is an umbrella term for distinct groups of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples.

• The world’s largest collection of contemporary Inuit art is at Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Qaumajuq, an Inuit art center that’s home to nearly 14,000 pieces and a three-storey visible vault.

• Artist Fredrick Lyle Spence, of the Peguis First Nation, gives soapstone carving workshops through Spence Custom Carving, including one I did at the Agowiidiwinan Centre at the Forks.

• Feast Café Bistro serves modern dishes rooted in traditional Indigenous food, while Promenade Brasserie bring French-Métis flavors to life.

• The Long Plain First Nation owns the Wyndham Garden Winnipeg Airport hotel, which is located on the city’s first urban reserve (Long Plain Madison Reserve) on Treaty 1 territory. Indigenous culture is woven throughout the design, food and artwork.

Winnipeg artist Fredrick Lyle Spence prepares for a soapstone carving workshop at the Agowiidiwinan Centre/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places