Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Yann Gavillot, geologist with the Geohazards Program at Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology.

Geological surface mapping has traditionally used aerial photos and direct observations through fieldwork, but the land surface is often obscured by vegetation. Recent advances in high resolution topographic datasets that use lidar have enabled geologists and earth scientists to virtually “remove” vegetation and reveal the bare earth ground surface—including, for example, active faults on the fringes of Yellowstone National Park. In 2022, a new lidar dataset for Park County, Montana, was released to the public.

Lidar stands for Light Detection and Ranging and uses a sensor commonly mounted on an airplane for large surveys. The lidar sensor rapidly emits laser pulses (>100,000 per second) that are reflected back from the ground surface or any object along their paths. The laser pulses that penetrate the vegetation have the longest travel times and thus are the last to return, and these are combined with GPS airborne and ground controls to generate a point cloud dataset that is used to build a high-resolution bare-earth digital elevation model (DEM) or digital terrain model (DTM).

Paradise Valley and gateway communities north of Yellowstone National Park not only have experienced rapid growth in population but also in annual visitors (more than 4 million visitors a year). Yet the many people that make the scenic drive to Gardiner at the northern park entrance may not realize the surrounding landscape has a rich record of prehistoric earthquakes that ruptured the ground surface, and numerous landslides of “gigantic” proportions. Although Yellowstone is more well known for its past volcanic eruptions and active hydrothermal systems, large damaging earthquakes and landslides have occurred in the region. The 1959 M 7.3 Hegben Lake event was the largest historical earthquake in the Intermountain West region, and it caused one of the largest seismically triggered landslides at Earthquake Lake, created extensive fault scarps, and altered geyser and hot spring activity through the park.

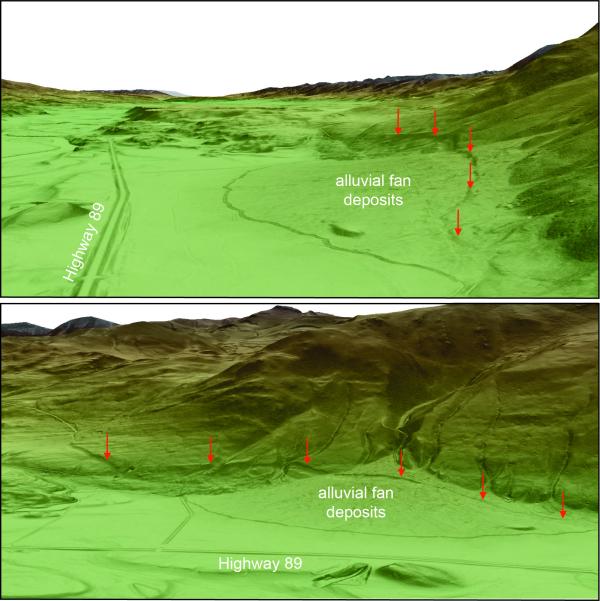

Shaded relief maps based on lidar data and showing fault scarps in Paradise Valley, Montana. Lidar imagery is given as a colored, shaded slope map, with higher elevations in brown and white, and lower elevations in green. Darker shading indicates steeper slopes. Top image is a northwestward view (toward Livingston) of Paradise Valley near Carbella. The right side of the image shows an oblique perspective of the Emigrant fault scarp (shown by red arrows) that vertically offset young alluvial fan deposits. Highway 89 is visible on the left side of the image as a pair of parallel lines. Bottom image is a southeastward view showing the same fault scarp. Subtle flutes and ridges extending horizontally across the hillslopes above the scarps were carved by glacial ice flowing down the Emigrant Valley from the Yellowstone ice cap. (Lidar visualization by Yann Gavillot, MBMG, using 3-D scene in ArcGis Pro).

These “cascading” natural disasters, like that of 1959, which caused nearly 30 fatalities and temporarily trapped about 250 people from blocked roads, provides an example of what could happen if a large earthquake were to occur in Paradise Valley. Geologists have recognized that the southwest limit of Paradise Valley had topographic steps, or scarps, which offset deposits that were less than 2.6 million years old. These are collectively referred to as the Emigrant fault and provide evidence that past earthquakes have happened in the area.

The recent lidar data have, for first time, revealed in greater detail an extensive and complex distribution of fault scarps of the Emigrant fault that extends nearly continuously for more than 33 miles (54 km) between Tom Miner Creek Road and Livingston, Montana. Fault scarps like these typically form when the ground ruptures during large earthquakes of magnitude ~6.5 or greater.

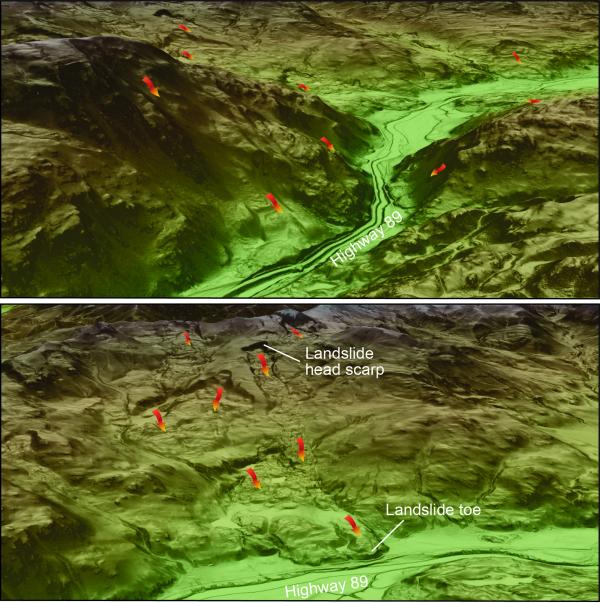

Lidar data have also revealed numerous fault scarps close to Gardiner in Montana that are likely associated with the East Gallatin-Reese Creek fault system that extends into Yellowstone National Park. Many large landslides also scar the landscape, and these are shown with exceptional clarity in the high-resolution lidar data. Some of these prehistoric landslides were so large that their run out extended for miles downslope and even blocked the Yellowstone River at Yankee Jim Canyon along highway 89, forming a temporary lake.

Shaded relief maps based on lidar data and showing landslides in the area of Yankee Jim Canyon, Montana. Lidar imagery is given as a colored, shaded slope map, with higher elevations in brown and white, and lower elevations in green. Darker shading indicates steeper slopes. Top lidar image is looking east at Yankee Jim Canyon along highway 89 showing numerous large prehistoric landslides (shown by colored arrows). With lidar data, one can identify, in great detail, the type of gravity-driven landslide and its transport direction, extent, and relative age. In the foreground, Highway 89 crosses the toe of a landslide that once to blocked the Yellowstone River but has subsequently been incised by the river. Bottom lidar image is northward view upstream of Yankee Jim Canyon, where one can see several landslides with long run outs between their head scarps (where they initiated) and toes (where they reached their downslope ends) that almost reach Highway 89. (Lidar visualization by Yann Gavillot, MBMG, using 3-D scene in ArcGis Pro).

This new lidar dataset offers an opportunity for geologists and hazards specialists to significantly improve hazards maps by allowing better characterization of the location, geometry, and activity of known faults and landslides.

The Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology is currently involved in developing and upgrading a statewide Quaternary fault and landslide database, utilizing newly released high-resolution topographic datasets such as the Park County lidar to generate county-wide hazard maps. These new datasets provide the information needed to improve assessments of potentially hazardous faults and landslides for future updates in county- and state-wide mitigation efforts for Paradise Valley and northern Yellowstone National Park, and contributing to the U.S. Geological Survey National Seismic Hazard Maps.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places