Pronghorn stand at the crest of a hill near the east slope of the Wyoming Range/Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Mark Gocke

Analysis Says "Path Of the Pronghorn" In Wyoming At ‘High Risk’ Of Being Lost

By Mike Koshmrl, WyoFile.com

The pathway of a highly migratory western Wyoming pronghorn herd that’s been known by researchers for a quarter-century is at “high risk” of being lost.

That’s according to a draft “threat evaluation” released Thursday by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in conjunction with an announcement that the state agency will consider identifying or designating migration corridors used by the Sublette Pronghorn Herd.

“In summary, the known current and potential threats pose a high risk to the functionality of the Sublette Pronghorn migration corridor,” the state’s evaluation reads. “The existing trend of suburban expansion and demand for renewable energy resources are the most concerning threats to the functionality of the corridor.”

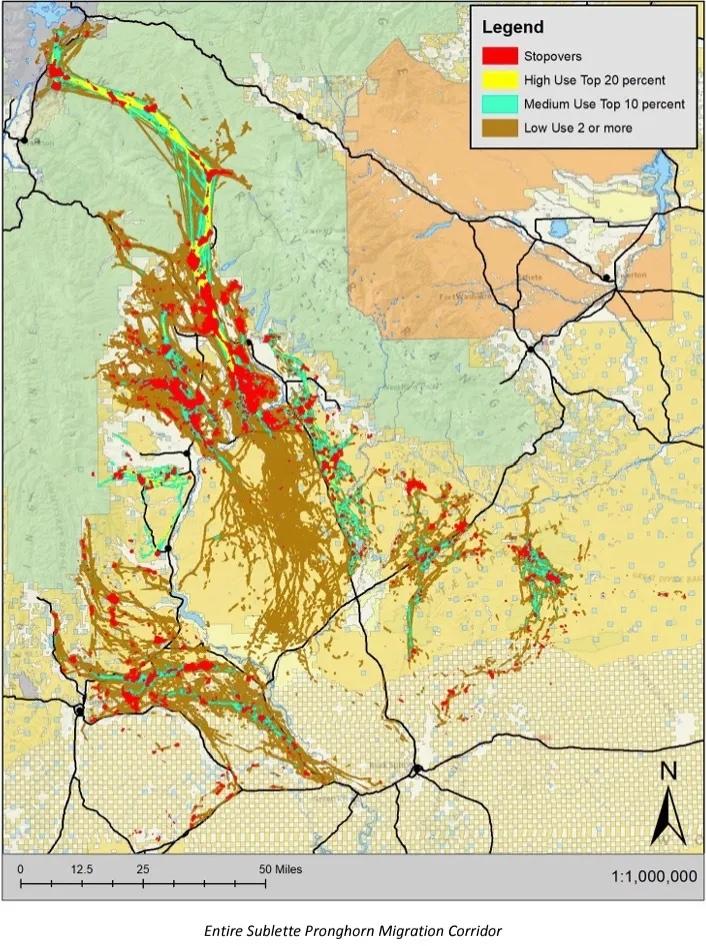

The 13-page report includes a map, which shows three primary migration areas.

The largest, northmost part of the corridor connects Grand Teton National Park to the Green River Basin’s sagebrush sea. The southernmost migration area runs from the east slope of the Wyoming Range to the lowest reaches of the basin and the Interstate 80 corridor, while two other smaller routes branch off the southern Wind River Range and tread through the Red Desert.

Until the deadly winter of 2022-’23, the Sublette Pronghorn Herd included roughly 40,000 animals, 75% of which were migratory. The corridors they use to migrate around the landscape are displayed here/Wyoming Game and Fish Department

Scientists built the map off of the movements of 415 GPS-collared pronghorn that transmitted location data from 2002 to 2022. Biologists learned that roughly 75 percent of the Sublette Herd was migratory, and they traveled between 6 and 165 miles, according to the threat evaluation.

Also known as the ‘Path of the Pronghorn,’ management of the Sublette Pronghorn Herd’s migration has been scrutinized because of a politically influenced delay in recognizing the corridor. Game and Fish hit pause on classifying the Path of the Pronghorn, and subsequently, Gov. Mark Gordon rolled out an entirely new process for designating migration corridors.

Then the new policy went unused for over three years while a series of developments advanced within the likely corridor, including subdivisions, a 3,500-well gas field and a recent Wyoming gas auction that leased out 640 acres for $19 an acre within a bottleneck section that could soon be classified as “high use.”

Refining the scientific method for translating raw GPS collar data into a mapped corridor was a big reason for the delay, according to Game and Fish Deputy Chief Doug Brimeyer. Specifically, University of Wyoming researchers and others were developing a new “line buffer” method — and the final product was just published in the Journal of Applied Ecology

“We’re glad to see that the science has improved enough that we feel comfortable with what the line-buffer method has outlined as being the corridor,” Brimeyer said. “I think people might be questioning, ‘Well, if you had 20 years of data, why wouldn’t we have done something sooner?’ But I hope they can understand that when we used the [old method] it was a very, very large footprint.”

Professional conservationists who’ve engaged in Wyoming migration politics welcomed the state taking a step toward designating the Path of the Pronghorn.

“I feel really confident that Game and Fish is doing the right thing here,” said Meghan Riley, the public lands and wildlife advocate for the Wyoming Outdoor Council. “We’re really excited to support them and the animals.”

Nick Dobric, The Wilderness Society’s Wyoming conservation manager, pointed out how the state’s potential auction of the tract known as the “Kelly Parcel” is yet another potential incursion into the pronghorn’s migration path.

“Designating the Path of the Pronghorn and managing the state lands it crosses as vital habitats, and in cooperation with federal land management agencies, is exactly the kind of action needed if Wyoming officials want to lead the way in migration corridor conservation and ensure the future of our prized wildlife,” Dobric said in a statement.

Game and Fish’s threat evaluation outlined other trends that don’t bode well for pronghorn. Sublette County’s human population grew 78 percent since 1990, adding barriers and stressors for the herd. Meanwhile, the herd just sustained its worst winter on record, a double whammy of weather and disease that left 75 percent of collared does dead by the spring thaw.

A group of pronghorn trots through the snow in the Green River Basin in April 2023. Best estimates are that 75% of the herd, last estimated at 43,000 animals, perished during the winter/WyoFile, Mike Koshmrl

Industrial development from the oil and gas and renewable energy industries was yet another “significant” pressure identified.

“In the Pinedale Anticline Project Area adjacent to the Jonah Field, [Hall Sawyer] demonstrated that pronghorn both avoid energy infrastructure and spend considerably less time in traditional winter ranges once habitat fragmentation occurs due to development,” the document says. “More recently, solar energy developments have been constructed in the southern portion of the proposed corridor near Green River and along the Gateway West Transmission Line.”

Fencing at the solar developments creates a “complete movement barrier to migrating pronghorn,” the evaluation says.

Although it’s officially begun, there’s a protracted process ahead to designate the Path of the Pronghorn. First, the state’s seeking public comment — remarks are due January 5. There are also three upcoming public meetings: at 6 p.m. Nov. 16 in Pinedale, 6 p.m. Nov. 29 in Green River and 6 p.m. Nov. 30 in Jackson.

The plan is for the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission to consider moving forward with a designation at its March meeting, Brimeyer said. If the commission gives the agency the go-ahead, there are many steps after that. A more detailed “risk assessment” must be completed, and a stakeholder group will also be assembled to review the proposal. After that, the designation goes back to the Game and Fish Commission.

And that’s not the end of it. Ultimately, the decision to designate the Path of the Pronghorn will be made by Gordon. Depending on how long it all takes, it could even be his successor making the final call.