The anchor of the steamship St. Lucie, which sank in 1906 during a hurricane, has been found in Biscayne National Park/Library of Congress, William Henry Jackson

An encrusted piece of maritime history has surfaced in Biscayne National Park, where archaeologists have discovered the anchor of a steamship that sank in 1906 during a hurricane, taking with it the lives of 26, including some early Miami pioneers.

The St. Lucie was carrying more than 100 people when it went down and became one of the worst confirmed maritime disasters in the waters of today's national park.

South Florida National Parks maritime archaeologist Joshua Marano located the steamship's anchor in July while visiting several archaeological sites with two interns hosted at the park and funded through the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project.

One of the anchors of the St. Lucie discovered in July in Biscayne National Park/NPS

“This find presents an opportunity to highlight a meaningful and tangible connection between a tragedy at sea happening within the current Biscayne National Park and broader historical events and challenges happening in Miami and throughout the region,” Marano said.

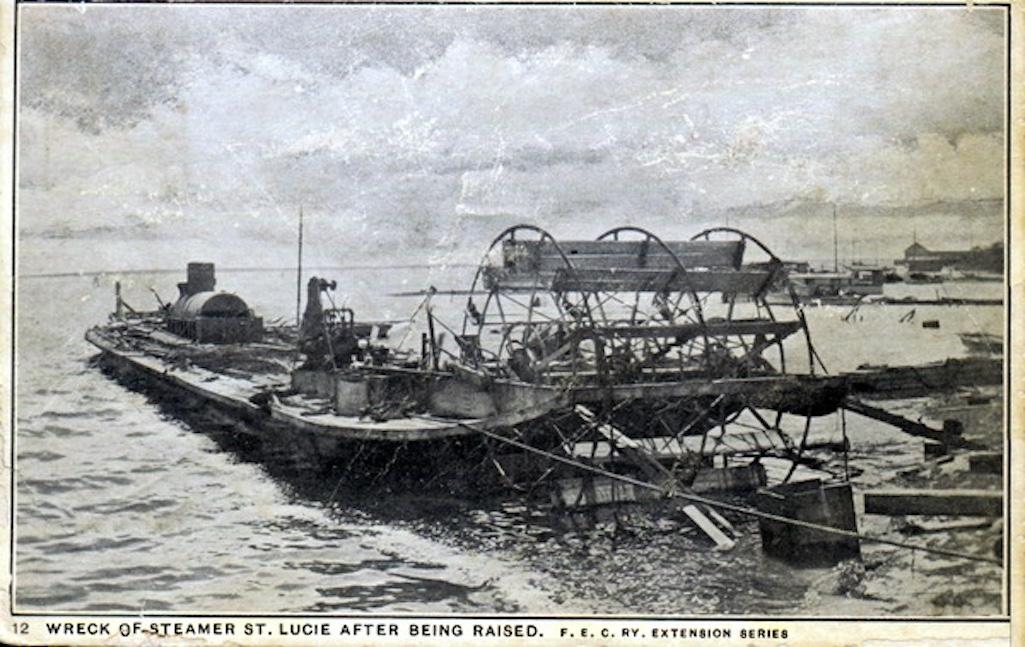

The St. Lucie was a stern paddle wheel steamer built in Delaware in 1888. With three decks, the 122-foot long ship boasted 14 staterooms and could reasonably carry up to 150 passengers. Drafting only 35 inches with a max speed of 10.5 knots, the steamer was ideal for navigating the inland waterways of Florida, and the vessel spent much of its early career carrying passengers and supplies along Florida’s Indian River between Titusville and Jupiter.

As the development and popularity of the railroad increased throughout Florida, travel by rail eventually surpassed steamship travel in many parts of the state. St. Lucie was one of eight shallow water vessels bought by the Florida East Coast Railway to ferry workers and supplies throughout the Florida Keys in the late 1800s. The extension of the railroad from Palm Beach to Key West at the convincing of early Miami pioneers Julia Tuttle and William Brickell spurred the rapid development of Miami in the early 20th century.

Carrying more than 100 laborers, engineers and railroad employees’ families, St. Lucie sailed into a fierce hurricane on October 18, 1906, while transiting between Miami and Knights Key. The vessel encountered the worst part of the storm about 25 miles south of Miami near Elliott Key, where it attempted to sail close to the shore and deployed several anchors to try to ride out the storm. The vessel eventually capsized in 13 feet of water and forced survivors to attempt to swim to the nearby island, which was nearly inundated by the storm surge. While Captain Steve Bravo was credited with doing all that he could to save the vessel and its passengers, 26 people died when the St. Lucie capsized.

St. Lucie’s hull was eventually raised, refitted and continued service in the Florida Keys for several more years, leaving very little evidence of the tragic events of that day. While it has been rumored that the dead from the disaster were buried on Elliott Key, the majority of those recovered were brought to Miami for internment. At least 21 bodies were recovered, and while several identified individuals were shipped to their homes or otherwise buried in private cemeteries, many were interred in two mass graves in the then-segregated Miami City Cemetery.

There are currently no plans to raise the anchor, given its large size and the costs of conservation. However, the park is working to produce digital interpretation of the artifact, including a 3D rendering that would be posted online. The anchor, as well as the nearby stranding site of St. Lucie, have been documented as archaeological resources and will be routinely monitored by members of the South Florida National Parks Cultural Resources Program along with more than 170 other archaeological sites both above and below the water.

Park staff have begun to work with stakeholders, including the City of Miami, Dade Heritage Trust, St. Lucie Historical Society, Historic Miami City Cemetery Restoration Committee and Florida East Coast Railroad to learn more about the vessel, identify the final resting places of the victims of the St. Lucie, and better tell the story of the early development of Miami. While the final resting place of 13 individuals who perished in the wreck of St. Lucie have been located, the remains of several African Americans who died in the wreck have yet to be found.

A postcard image of the St. Lucie after it was raised/Public domain

Since 2018, the park has served as a host site for the Slave Wrecks Project internship, which helps to expand the pool of underwater archaeologists by providing diverse students with experience in marine field operations, scientific diving, historical research, education and outreach. The discovery of the anchor provided an opportunity for the interns to apply their newly developed skill sets as they performed detailed site documentation, identifying features that provided more information about the anchor’s age and the size of the vessel that would have carried it. Following field work, both the interns and park staff continued to perform targeted archival research in park records, local archives and historic newspaper accounts.

Visitors to Biscayne National Park are reminded that submerged cultural heritage is protected under federal law.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment