Bellevue House National Historic Site in Kingston, Ontario/jennifer Bain

The first thing you see when you arrive at a grand property where Canada’s first prime minister lived on his way up the political ladder is a mural called “Creator’s Drum” by Indigenous graphic designer and artist Chris Mitchell.

It’s printed on a vinyl canvas that hangs on the gable of the Bellevue House National Historic Site visitor center. The mural signals that this bucolic 2.5-acre site in an affluent neighborhood of Kingston, Ontario is no longer just a one-sided celebration of colonial history.

“It’s a piece of welcoming and coming together,” explains Parks Canada’s Indigenous relations liaison Aarin Crawford.

Glooscap, the Mi’kmaq creator, leads the community in song, beating on a drum that represents the heartbeat of Mother Earth. A rainbow signifies sunnier days ahead. Two foxes flank the people, serving as a nod to a den that has been on this property for two decades, and representing “people living in harmony with all of creation.”

Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada's first prime minister, died in 1891 and his mixed legacy is explored at Bellevue House National Historic Site in Kingston, Ontario/Jennifer Bain

I’ve come to this city three hours east of Toronto to preview how Bellevue House will tell its complicated story and embrace neglected perspectives when it opens for the season on May 18. Exhibits in the visitor center — a reconstructed coach house — have been updated and decolonized. The heritage house is reopening after a six-year renewal project. Indigenous art is featured on new signage across the grounds.

Guided tours like mine will start with a “Kingston before Sir John A. Macdonald” moment asking people what they think existed here before colonization. There will be a “more heartfelt” land acknowledgement than the box-checking kind that has become the norm, and explicit gratitude to the Wendat, Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe people for all their contributions to Canada.

Macdonald died in 1891, but the nation-building politician has been recently “cancelled” by many. He is now known as the prime minister who helped create the residential school system that forcibly separated Indigenous children from their families and sent them to boarding schools — run by the church — where they were humiliated, mentally, physically and sexually abused, and even killed.

Parks Canada's Tamara van Dyk, historic sites and visitor experience manager, shows off frank new signage at Bellevue House National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

Macdonald campaigned on the promise of a railway linking the country from coast to coast, but after using Chinese migrants to build the Canadian Pacific Railway he launched a racist Chinese Head Tax to curtail immigration.

“No single perspective tells the whole truth,” interpretive signage at Bellevue House notes, “but together, the conversations can illuminate a complicated history.”

Statues of Macdonald have been defaced, toppled and removed across Canada. Businesses and roads bearing his name have been renamed. Bellevue House, perhaps because Macdonald isn’t in its name, or because it’s off-the-beaten path in a residential area, hasn’t really been a target of cancel culture. But frank new signage gamely confronts Macdonald’s mixed legacy.

“He’s a monster.”

“I never learned that in school.”

“He was a product of his time.”

“That happened a long time ago.”

“We wouldn’t have Canada without him.”

The Tall Ones, by artist Melissa Brant, illustrates an interpretive sign about what the land was like at Bellevue House before colonization/Jennifer Bain

As we stroll the grounds, I hear how the Bellevue House Community Advisory Committee (with 12 Indigenous and non-Indigenous members) felt Indigenous art should be included with diverse perspectives in the renewal project. Nobody was sure how artists would respond to the callout, but a number of them stepped forward with ideas.

Macdonald was born in Scotland and brought to Canada as a child. He became a lawyer and aspiring politician and rented Bellevue House in 1848 and 1849 with his ailing wife Isabella and first son John Alexander (who would die when he was just 13 months old).

Kingston, at that time, was the first capital of what is now Canada. The wealthy and elite were leaving downtown and building “country” homes in an area that’s now near Queen’s University and the former maximum-security prison that’s now Canada’s Penitentiary Museum.

Bellevue House, home to Canada's first prime minister in 1848 and 1849, will reopen in May after a six-year renewal/Jennifer Bain

First built around 1841 for tea merchant Charles Hale, “Villa Bellevue” is a 3,800-square-foot Tuscan villa-style home with four floors with seven split levels. It has been recognized for its architecture (Italianate in the Picturesque manner) and has been restored to the period that Macdonald lived in it. He dubbed it the Pekoe Pakoda. Others called it the Tea Caddy Castle.

I’m touring with Crawford, Elizabeth Pilon (Bellevue House renewal project lead), Tamara van Dyk (historic sites and visitor experience manager) and Guy Thériault (senior marketing specialist responsible for travel media relations).

When we arrive at the impressive and unusual house, we draw numbers. The person with number one gets welcomed by servants at the front door, while the rest of us are redirected to the back door.

Only the privileged few could enter Bellevue House through the front door. Everyone else had to go around to the back door/Jennifer Bain

We learn that “twos” are live-in servants like butlers and cooks, “threes” are daily workers like stable hands, “fours” are delivery and trades people, and “fives” are what’s known as “the uninvited.” The thought-provoking activity works well with schools and larger groups.

Inside, I’m impressed to see Indigenous perspectives included in each room. A laminated lexicon offers a primer on words like colonialism, genocide, racism and democracy. A content warning about residential schools, assimilation, colonial impact and ongoing trauma directs people to a toll-free national residential school crisis line.

In the parlor, I read how Indigenous societies measure status, rank and prestige through respect, friendship and generosity. Before colonization, Indigenous homes were filled with tools to be shared.

In the kitchen, I learn about the hierarchy of domestic staff and the way that European occupation adversely impacted Indigenous diets.

The formal dining room at Bellevue House speaks to the customs of the privileged elite/Jennifer Bain

Looking at a picture perfect Victorian dining room that many would admire, I am asked to consider how Indigenous culture and traditions were stolen through colonization and assimilation.

Walking upstairs, I hear Indigenous drumming. “Wildflower” by Barbara Hooper is about grandmothers calling children back to safety and the mesmerizing song ensures the Indigenous perspective is heard and not just seen.

In a lavish guestroom, a multimedia display called “Many Voices” provides videos of people sharing Indigenous, Chinese, Black, female and Irish perspectives.

In a guest room at Bellevue House, Parks Canada's Aarin Crawford shows a video display that speaks to who was and wasn't invited into colonial homes/Jennifer Bain

Another video plays on a loop in the principal bedroom and features two Indigenous Elders and four children talking about important teachings. In the same room, you can collect “tearaways” that share sacred teachings from two Indigenous nations.

The nursery, predictably, showcases a Gothic Revival cradle that the Macdonalds likely brought over from Scotland. But the wooden cradle is juxtaposed with a wooden cradleboard and insight into the way that Indigenous mothers kept their babies close.

It’s in the nursery that I read more about how residential schools opened in what’s now Canada in the 1830s, but how it was Macdonald who authorized the creation of a federal residential school system in 1883. Children as young as four were forcibly separated from their families and subjected to “violent assimilation and abuse,” prevented from practicing their culture, and forbidden from speaking their languages.

“This system created continued, intergenerational, and devastating impacts on Indigenous communities,” a sign explains.

In the principal bedroom, a video featuring two Indigenous Elders plays on a continuous loop/Jennifer Bain

Parks Canada purchased the Bellevue House property in 1964 after deciding it needed a place to honor Macdonald. It opened to the public three years later as Canada turned 100.

By 2015 — the 200th anniversary of Macdonald’s birth — Parks Canada realized it was time to start expanding the story here and including multiple perspectives. That happened in 2016, just before 2017 when many Indigenous people let it be known that they wouldn’t be celebrating Canada’s 150th birthday.

“We saw the need to change exhibits and be more open, truthful and inclusive,” says Pilon.

Then in 2021, Canada was rocked by the suspected discovery — through ground-penetrating radar — of unmarked graves at a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. Claims of similar discoveries have since been made across the country.

In the nursery, a wooden cradleboard, baby moccasins and a beaver pelt speak to the way that Indigenous Peoples consider plants, animals and "All of Creation" to be relatives/Jennifer Bain

As all this was happening, Bellevue House was closed for a renewal and Parks Canada was preparing to update the site’s 2004 management plan. Staff pledged to prioritize Indigenous reconciliation, engagement and involvement.

In an unusual move, the new plan came out in 2023 and starts with a full-page message from the Bellevue House Community Advisory Committee.

“It is time to be curious, to ask respectful questions, and to listen to the conversations,” the committee writes. “Sir John A. Macdonald is an integral part of Canada’s history and Bellevue House is a historic symbol of that story. However, we need a more complete picture of the man’s legacy; a picture that includes everyone.”

The Fathers of Confederation, painted by Robert Harris, shows an 1864 scene with Sir John A. Macdonald standing and holding a paper. There are no women or Indigenous people/Jennifer Bain

Macdonald could no longer be simply glorified as a nation builder. The painful impacts of settler colonization on Indigenous peoples could no longer be overlooked. Parks Canada would present a more complete picture of Macdonald without positioning itself as “the arbiter of truth.”

Bellevue House is open from May to October. It draws 15,000 to 20,000 visitors, some arriving by car and others with Kingston Trolley Tours.

Everyone is greeted by a welcome sign in five languages — English, French, Mohawk, Algonquin and Métis. In the visitor center, where you must go to pay an entrance fee, color-coded interpretation is black for the colonial perspective and purple for Indigenous and other diverse views.

“It sets the tone for the experience to be many voices,” explains van Dyk.

In the visitor center at Bellevue House, Parks Canada starts to explore Sir John A. Macdonald's mixed legacy/Jennifer Bain

Bellevue House now considers itself “a place to explore the complex legacy of Canada’s first prime minister and have conversations about Canadian history.” People can unpack themes of colonial power and privilege while considering the perspectives of Indigenous people, visible minorities, women and marginalized communities.

“I don’t believe in the adversarial forms of reconciliation,” Sheldon Traviss tells me in the visitor center. He’s part of the Mohawk Nation and will be the firekeeper at the May 18 reopening event. His late mother Laurel Claus Johnson, an Elder from the Bear Clan of the Mohawks, was on an Indigenous Working Circle that helped guide the Bellevue House renewal.

As I tour the grounds — with its Victorian ornamental and heritage kitchen gardens and heirloom apple orchard — I hear Parks Canada staff grappling with what name to use for Macdonald. On first reference, most refer to him formally as Sir John A. Macdonald, but after that there’s flexibility to switch to Macdonald or John A.

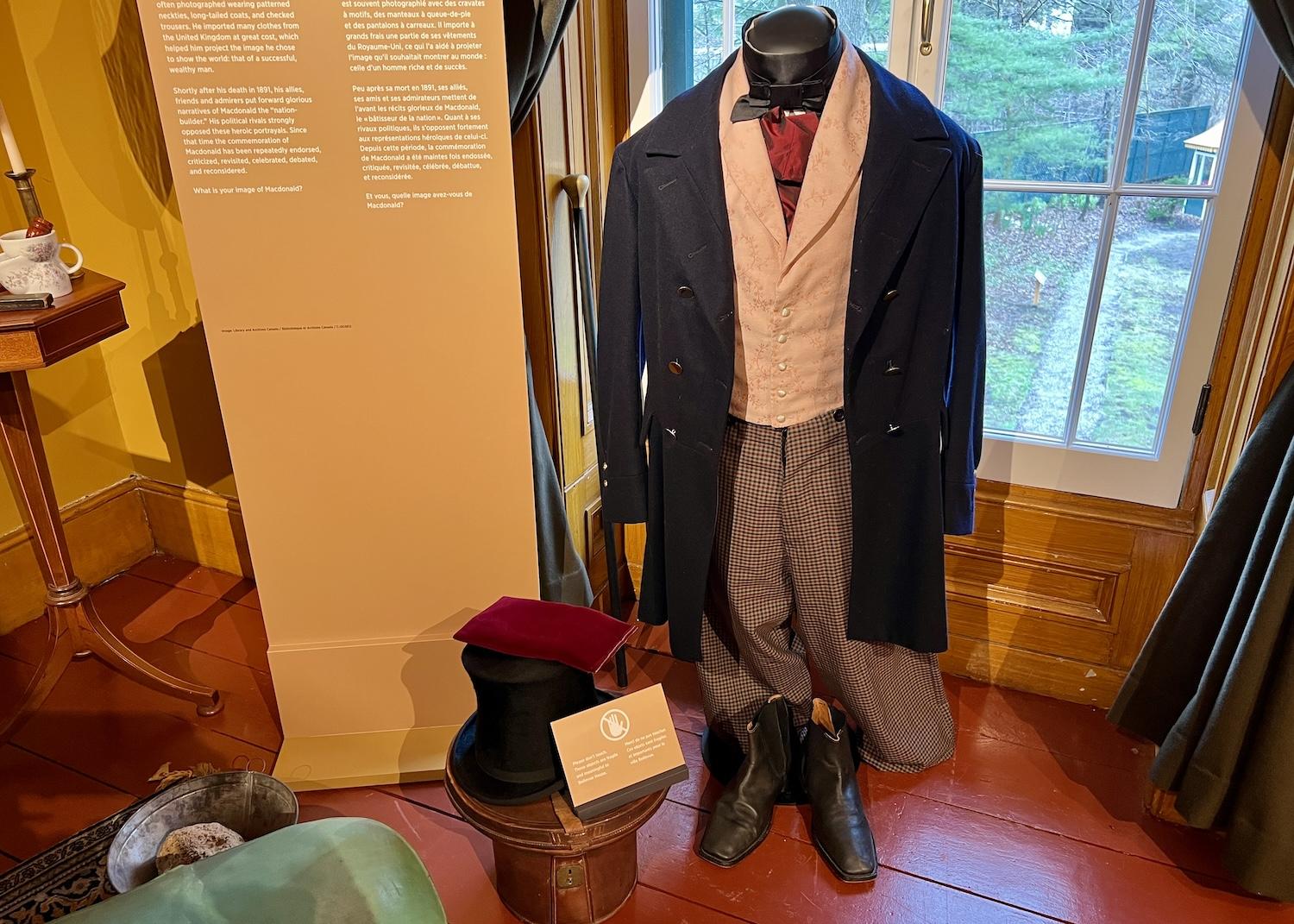

Sir John A. Macdonald was known to import expensive clothes from the United Kingdom/Jennifer Bain

When I ask Crawford to show me the part of the historic house that’s most meaningful to her, she takes me to a room that was likely Macdonald’s dressing room.

Macdonald “dressed with flair” and loved patterned neckties, long-tailed coats and checked trousers. He imported expensive clothes from the United Kingdom to project the image of a successful, wealthy man — even when he was merely renting this lavish house.

One of Macdonald’s outfits is on display. But there’s also an eye-catching red ribbon skirt on display. It’s here to tell the story of Isabella Kulak who was shamed for wearing a traditional ribbon skirt to her Saskatchewan elementary school’s formal dress day in 2020 when she was 10.

Parks Canada's Aarin Crawford stands by an Indigenous ribbon skirt that symbolizes an important and recent story about what happened to a Saskatchewan girl on a formal dress day at school/Jennifer Bain

Kulak received support from outraged Canadians and an apology from her school. In 2023, Canada started celebrating National Ribbon Skirt Day every Jan. 4 noting that the skirt is a centuries-old spiritual symbol of womanhood, identity, adaptation and survival and helps women to honor themselves and their culture.

The red skirt on display was crafted by Judi Montgomery. A photograph of Kulak, wearing her own ribbon skirt, has been shared with permission from her family. I hear how Parks Canada flew the family to Bellevue House to see the exhibit before it opens to the public.

“It was just a really joyful meeting,” remembers Crawford.

The red skirt story fits beautifully with one of Bellevue House’s key messages. Change can come from anyone — not just politicians, civic leaders and activists — and we can all help make Canada more inclusive.

One activity at Bellevue House asks visitors different questions about their dream country/Jennifer Bain