Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Michael Poland, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey and Scientist-in-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

The hydrothermal explosion at Biscuit Basin on July 23, 2024, was a spectacular event and emphatically demonstrates an under-appreciated hazard in the Yellowstone region.

Shortly before 10 a.m. on July 23, 2024, an explosion of hot water, mud, and rock occurred from Black Diamond Pool in Biscuit Basin, Yellowstone National Park, only about 2 miles northwest of Old Faithful. No precursors to the event were detected by monitoring instruments. Dramatic videos posted to social media showed a plume of water and rock fragments rising about 600 feet (180 meters) into the air as people ran for safety. The explosion heavily damaged the nearby boardwalk, and the basin remains closed as geologists assess the activity. Thankfully, no one was injured.

Map of major thermal features in Biscuit Basin, Yellowstone National Park. Base map from Google Earth.

Geologists examining the deposit have noted that the rocks thrown out by the explosion were composed of glacial materials, sandstones and siltstones, and gravels that immediately underlie the silica sinter that forms a veneer on the surface. None of the rhyolite bedrock that is present about 175 feet (50 meters) beneath the surface (based on drilling in the 1960s) was found. This indicates that the explosion was generated at a depth much shallower than that to have not disturbed the bedrock. This is not surprising, because hydrothermal conduits mostly exist at shallow levels beneath the surface in Yellowstone.

The explosion was largely directed to the northeast toward the Firehole River (away from the boardwalk), and the largest boulders—some measuring several feet across and weighing hundreds of pounds!—fell in that direction. This fortuitous directionality was probably the reason that no one standing on the boardwalk at the time of the event was injured.

This boulder is the largest that is confirmed to have been part of the July 23, 2024, hydrothermal explosion from Black Diamond Pool, Biscuit Basin, Yellowstone National Park. The tape measure is 50 centimeters (20 inches) long. Black Diamond Pool and a boardwalk are in the background. The foreground is scattered with smaller rocks that were part of the explosion. Photo by Lauren Harrison, Colorado State University, on July 25, 2024.

Aerial view of Biscuit Basin, Yellowstone National Park, showing debris deposited by the July 23, 2024, hydrothermal explosion from Black Diamond Pool.Major features are labeled. The main debris field (within dashed yellow line) has a gray appearance. Photo taken by Joe Bueter, Yellowstone National Park, on July 23, 2024.

Hydrothermal explosions occur when liquid water boils and converts to steam in the shallow subsurface. This sort of transition happens all the time in established geyser systems, like Old Faithful or Steamboat Geyser, where well-defined conduit systems allow that steam and hot liquid water to take an unobstructed path to the surface, resulting in a geyser eruption. But when the liquid-steam mixture is within a confined space that has become sealed and without that well-defined conduit system, pressure due to the expansion of steam bubbles eventually overcomes the strength of the rock, and an explosion occurs.

In the case of Black Diamond Pool, the July 23 explosion was probably caused by a change in the hot-water reservoir in the shallow subsurface. Silica precipitation can clog conduits or “pipes” in the reservoir leading to accumulation of steam and a pressure buildup. The data that geologists are collecting from the explosion debris will provide even more detail on the exact conditions at the time of the event.

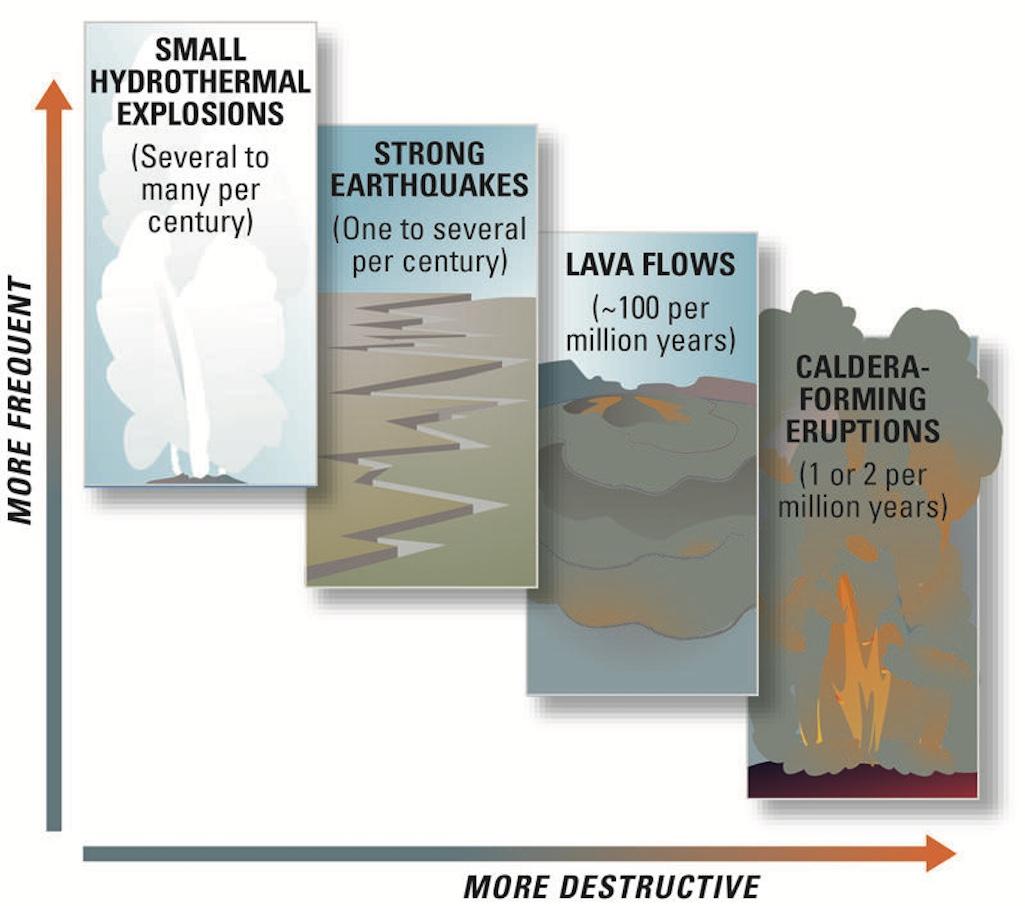

Hydrothermal explosions are more common than you might think in Yellowstone National Park. They are the most frequent yet least destructive hazard, compared to strong earthquakes, lava flows and domes, and caldera-forming eruptions. On average, there are a few hydrothermal explosions of varying sizes somewhere in Yellowstone National Park each year, often in the backcountry where they may go unnoticed.

Scientists evaluate natural-hazard levels by combining their knowledge of the frequency and the severity of hazardous events. In the Yellowstone region, damaging hydrothermal explosions and earthquakes can occur several times a century. Lava flows and small volcanic eruptions occur only rarely—none in the past 70,000 years. Massive caldera-forming eruptions, though the most potentially devastating of Yellowstone’s hazards, are extremely rare—only three have occurred in the past several million years. Recurrence intervals of these events are neither regular nor predictable/USGS

Some of the largest hydrothermal explosions of the past 150 years in Yellowstone National Park occurred in the 1880s at Excelsior Geyser, which is adjacent to Grand Prismatic Spring in Midway Geyser Basin. The September 1989 explosion of Porkchop Geyser, in Norris Geyser Basin, might be among the most famous hydrothermal explosions in a well-known area. That was witnessed by several visitors but did not cause any injuries. Another small explosion occurred in Norris Geyser Basin more recently on April 15, 2024. This event was detected by nearby monitoring instruments that were specifically designed for that purpose. Without data from those instruments, that unwitnessed event might never have been recognized. In the monitoring plan for Yellowstone that was released in 2022, the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory specifically targeted an expansion of hydrothermal monitoring as a goal to address the threat posed by these small but hazardous hydrothermal explosions. Monitoring equipment installed in September 2023 in Norris Geyser Basin is a first step towards realizing that goal.

Much smaller events are even more common—for example, the 2018 rare eruption at Ear Spring, near Old Faithful Geyser. That eruption brought several decades of human garbage to the surface. But larger events can also occur. Since the last ice age ended in the Yellowstone area about 14,000 years ago, there have been more than a dozen hydrothermal explosions that left craters hundreds of feet across. The largest such crater—indeed, the largest hydrothermal explosion crater known on Earth!—is about 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers) across and formed in an event approximately 13,000 years ago at Mary Bay, along the north part of Yellowstone Lake.

It is too early to tell what might be next for Biscuit Basin. The explosion clearly changed the shallow hydrothermal flow paths in the area, and it is unknown how the thermal features will respond. Did we witness the birth of a new geyser? Will activity return to its previous calmer state, and a placid hot spring will reform? Data being collected by geologists will help us to better understand the July 23 event and how the area might evolve in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Many YVO scientists contributed to this article, especially Shaul Hurwitz and Mark Stelten (USGS), and thanks to Lauren Harrison (Colorado State University), Mara Reed (UC Berkely), and Jeff Hungerford, Kiernan Folz-Donahue, and Elle Blom (Yellowstone National Park), who led the field response to the July 23 explosion.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places