For those who love geopolitical anomalies, there’s a tiny uninhabited island in northern Maine that you’re not supposed to visit but can learn about from American and Canadian parks set up on opposite sides of a tidal river that empties into the Bay of Fundy.

Well at least the U.S. National Park Service and Parks Canada call it the same thing — Saint Croix Island International Historic Site. Or, as Kurt Peacock, historic sites lead for Parks Canada in southern New Brunswick, puts it, “it’s an island of international importance.”

To unravel this intriguing story, I grab my passport and head to Maine.

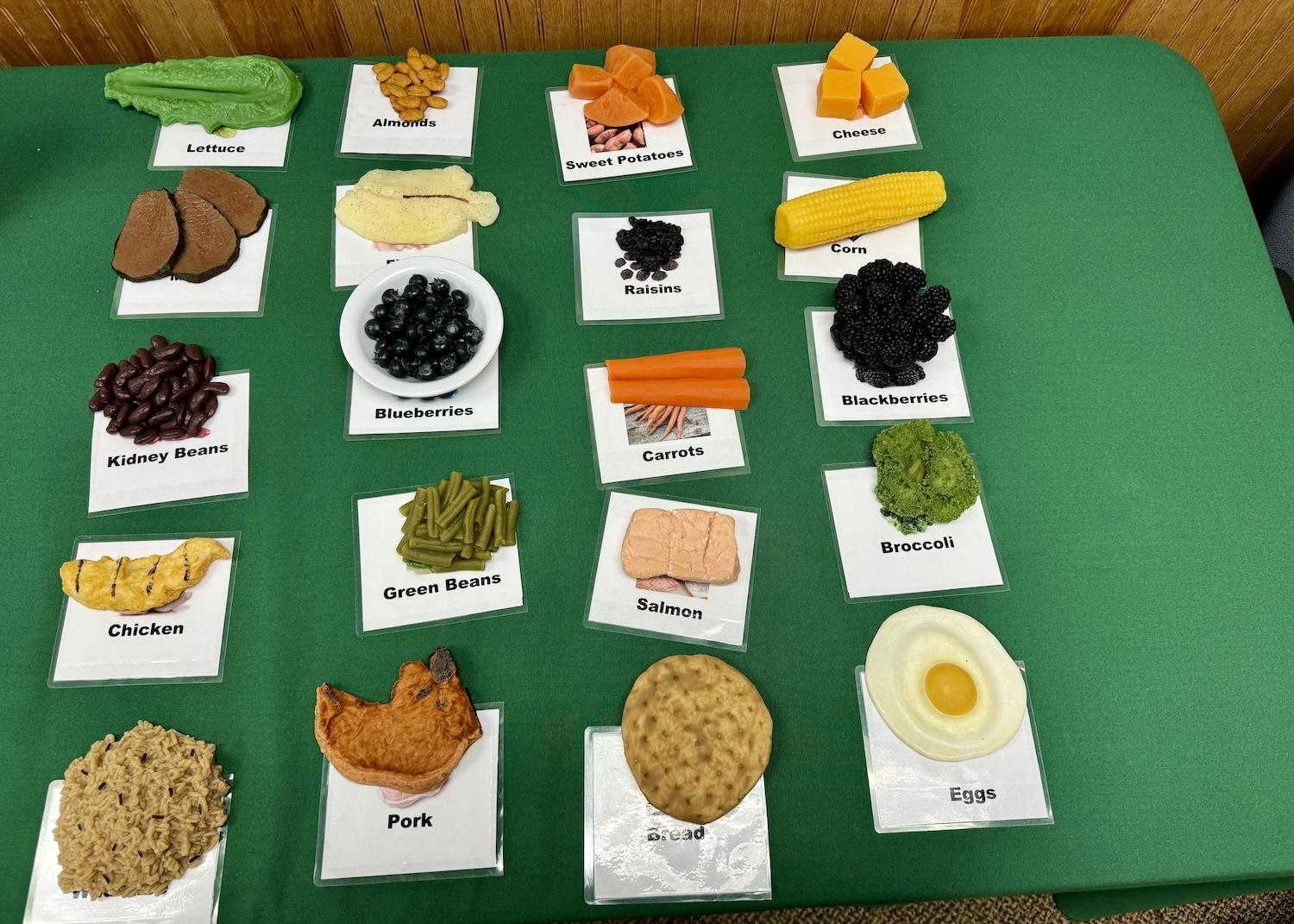

In the NPS ranger station for Saint Croix Island International Historic Site, you can use these plastic foods to learn about Vitamin C and scurvy/Jennifer Bain

Michael Zwelling, site manager on the NPS side of things, welcomes me to the ranger station in the southern end of Calais, points to 20 pieces of plastic food and tells me to choose five to survive winter on an island.

Wild rice, meat, blueberries, sweet potatoes and broccoli sound like well-balanced rations, but when Zwelling flips them over it’s to see how much Vitamin C each contains. If I get four points or less, I will die of scurvy, five to nine and I’ll get the disease but survive, 10 or more and I’ll be just fine.

I get 10 points, but that’s just by dumb luck.

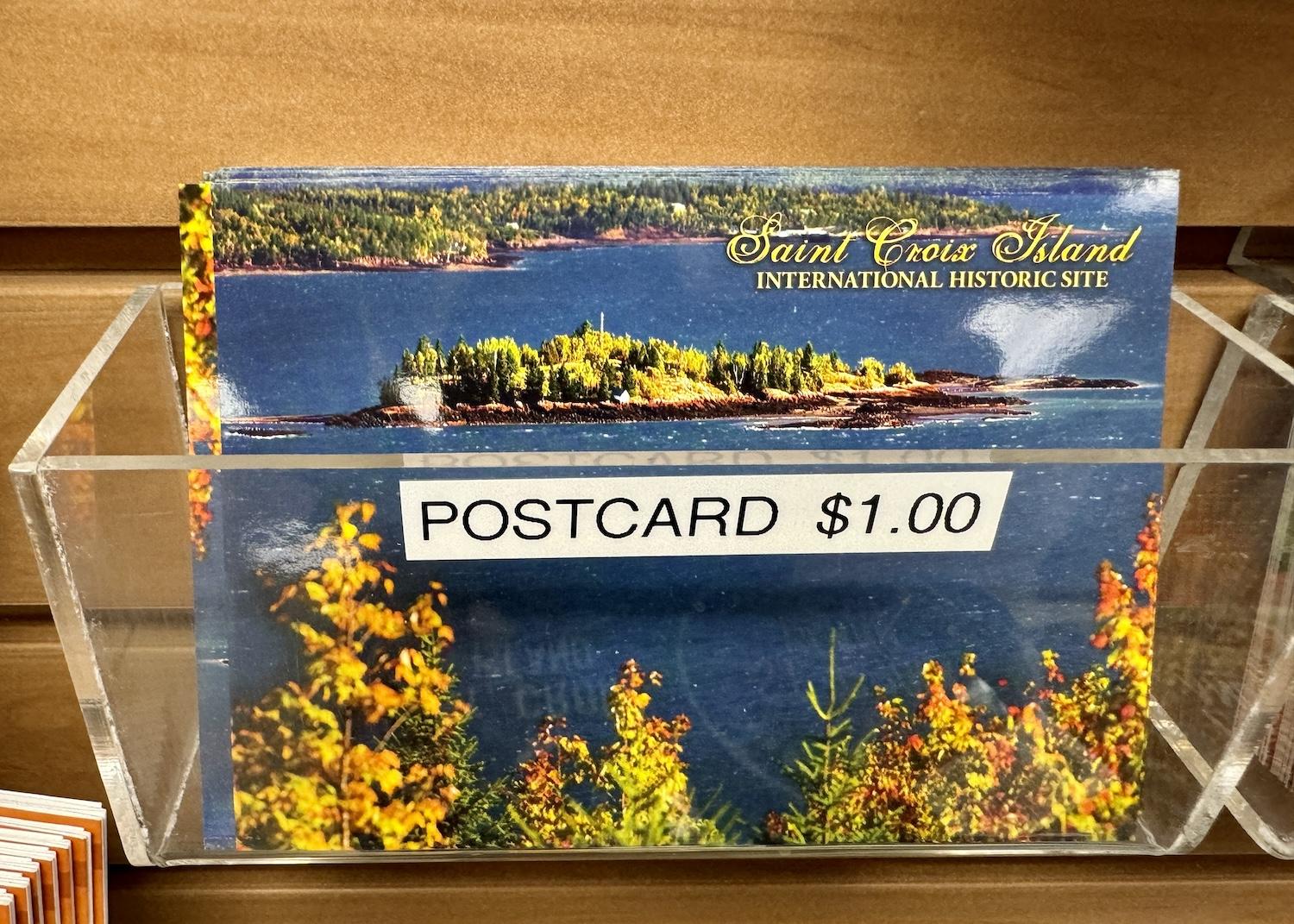

In the U.S. ranger station gift shop, a postcard showcases the island that you're supposed to look at from shore but not visit/Jennifer Bain

When the French sailed around Nova Scotia to the top of the Bay of Fundy and down to what’s now New Brunswick and Maine in 1604, they planned to colonize an area they called l’Acadie. Led by Pierre Dugua, they settled on Saint Croix Island at the confluence of two rivers and against the advice of the Passamaquoddy people who had lived in the area for centuries.

The 79 French colonists thought they were prepared for winter, but 55 men got sick and 35 died after harsh weather trapped them on the island. They didn’t know they needed Vitamin C-rich foods so scurvy wouldn’t attack their connective tissue, cause their teeth to fall out and even kill them. If only they had made tea from white pine or spruce like the Passamaquoddy did.

Now that I can better empathize with those men — who included cartographer Samuel de Champlain — I can delve into the repercussions of their explorations.

Michael Zwelling, site manager for Saint Croix Island International Historic Site in Maine, stands by the Saint Croix River in front of Saint Croix Island/Jennifer Bain

“Saint Croix Island is the site of the first French landing in this part of North America and it’s the start of the spread of the French culture throughout Canada, and so we preserve the island to tell that story,” Zwelling explains. “But along with that story we tell the story of the Passamaquody who were here at that time — because oftentimes that story is lost — and we talk about European exploration.”

As spring arrived in 1605 and the Passamaquoddy and other Wabanaki tribes returned to trade fresh game for bread, the surviving French explorers healed. The expedition soon packed up their structures and left to settle in Port Royal in today’s Nova Scotia, but the French presence in North America had begun. The short-lived settlement predated the British colony of Jamestown, Virginia by three years.

The island, now with a small cemetery, was abandoned and so was a mainland spot where the colonists built gardens and a hand mill. A U.S. Coast Guard Light Station was later established on the island. On the mainland of what’s now Maine, locals used a “red beach” area for shipbuilding and other industries. Nothing remains of these two uses, but millions of people of French-speaking origin now live in Canada and the United States.

A bronze relief map of the ill-fated 1604 French settlement on Saint Croix Island can be found at the NPS site in Maine/Jennifer Bain

On the government front, Congress authorized the establishment of Saint Croix Island National Monument in 1949. It was redesignated an international historic site in 1984 in recognition of the “historic significance to both the United States and Canada.”

When I pick up the NPS brochure and map for Saint Croix, I’m surprised to see it’s in English and French. There is no ferry to the 6.5-acre island that the NPS says isn’t accessible to the public “due to dangerous currents, fragile ecosystems and protected archaeological resources.”

Instead, you’re encouraged to look at the island from the 21.94-acre mainland site, which includes an interpretive trail, bronze statues, viewing shelter and bronze model of the 1604 settlement. There’s also a rocky beach, primitive boat ramp and occasional ranger-led tidepool talks, plus a lease up for grabs for the historic McGlashan-Nickerson House, an 1883 Italianate-style house built for the Scottish immigrant who helped establish the Maine Red Granite Co. here.

Saint Croix Island site manager Michael Zwelling stands by a bronze that speaks to how French colonists set up on the Passamaquoddy homeland/Jennifer Bain

Strolling down the Wonessonuk Trail — installed in 2004 to mark the 400th anniversary of the French landing — I admire seven bronzes that tell the story of the failed settlement. Nobody will stop you from kayaking or boating to the island, Zwelling admits, but the river has dangerous 20-foot tides and visitation windows are small.

In 2004, French, Canadian, Passamaquoddy and American officials were transported to Saint Croix Island for a 400th anniversary celebration that lasted one hour. Everyone exchanged gifts and expressed their hopes for continued good relations among the four nations. More recently, NPS staff visited with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Parks Canada to see how to slow down natural erosion that is being accelerated by climate change. A report is pending.

Last year, 12,432 people visited this American unit, many daytripping 120 miles from Acadia National Park mainly to get their NPS passport stamp (which is conveniently kept in a box outside the ranger station).

At the Canadian lookout to Saint Croix Island, a 2004 triptych (a sculpture in three panels) is showing its age/Jennifer Bain

Rangers also tell people they can drive to the Canadian side of the international park about 40 minutes and one time zone away. Parks Canada established its Saint Croix Island International Historic Park in 1997 in Bayside, just north of St. Andrews, and offers a self-guided interpretive trail with views of the island.

My two-nation exploration of all things Saint Croix continues in Canada.

Guided by Peacock, I explore the small lookout area with a huge parking lot that logs about 10,000 visitors a year. The interpretive signs are dated and a kitchen shelter and three-part artwork haven’t aged well. But there are five flags, one each for Canada, New Brunswick, the United States, Acadie and the Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik (what the Passamaquoddy call themselves here).

Five flags, including one for the Indigenous nation that first lived in this part of New Brunswick, fly at Canada's Saint Croix Island International Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

With my zoom lens, I can just make out buoys that mark the international line. Parks Canada doesn’t own the land between the lookout and river, though, so I can’t walk down to the water.

“You get a chance from this vantage point to see just how small and humble the island is,” Peacock muses, “but one of the challenges is we’re going to have to cut some of the trees to see the island itself. We need to have a better lookout, and we’re going to have to figure out some proper vegetation management. To transport the visitor back in time 400 years can be challenging when you see power lines and modern homes nearby.”

Parks Canada's Kurt Peacock stands in a picnic shelter meant to evoke a primitive kitchen shelter/Jennifer Bain

As we wrap up, he shares a final twist to the story.

When deciding the border between Canada and the United States in this area (which again was the Passamaquoddy homeland), the two nations disagreed over which river was the Saint Croix. But a New Brunswick surveyor using Champlain’s maps and documents proved that Dochet Island (as Saint Croix Island was then called) was the former site of Dugua’s settlement.

This and other evidence convinced the Boundary Commission to set the Saint Croix River as the international boundary in 1797, using archaeological techniques to solve an historical question for the first time in North America.

“It’s kind of a neat epilogue to the story of the island,” says Peacock. “So the island has relevance to both the Canadian and American nations largely because of its relevance to the question of the border.”

Parks Canada's Kurt Peacock shows how you can only view Saint Croix Island from afar while at the Canadian side of the international historic park/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment