It’s just a titch late in the breeding season and the elusive Bobolinks are nowhere to be found in a rare grasslands patch of Rouge National Urban Park that’s off-limits to the public. But that doesn’t stop ecologist team lead Leonardo Cabrera from setting up his high-definition soundscape recording system and calling for quiet as he captures some audio.

He pulls out his phone and plays a YouTube clip of the Bobolink’s joyous, bubbling song. He shows a photo of a gorgeous breeding male that looks like it’s wearing an upside-down tuxedo because of its white back and black underparts.

“This is just a tool,” Cabrera says of his fancy equipment.

When we don't see or hear Bobolinks, Parks Canada ecologist Leonardo Cabrera calls up photos and recordings of the threatened species on his phone/Jennifer Bain

“I keep promoting conscious listening to help you go in the direction of increasing those relationships with nature. Because you are actually paying attention, you are actually understanding — or trying to understand — how these animals are telling you about potentially this is a new species or this is a species that doesn’t belong here too much. So by actually understanding and by consciously listening, I think that’s an important link to actually care for the environment.”

I’ve come to Rouge just after sunrise in mid-July to see how this park has responded to a study about the impacts of climate change on the distribution of birds in Parks Canada places.

Rouge is a jagged, sprawling park-in-progress that spans the Greater Toronto Area from Uxbridge to Markham and Scarborough, linking the Oak Ridges Moraine to Lake Ontario. More land transfers are expected and there are hundreds of access points.

It's tick territory in parts of Rouge National Urban Park in the Greater Toronto Area/Jennifer Bain

Locally and globally, birds and their habitat ranges are being impacted by a warming planet. The 2018 “Birds and Climate Change” study by the U.S. National Park Service and National Audubon Society predicted an upheaval of the species we see in national parks.

More recently, Parks Canada teamed up with the National Audubon Society, Canadian Wildlife Service and Birds Canada to study 434 bird species at 47 of its sites. “Projected Effects of Climate Change on Birds in Parks Canada Protected Areas” concluded that one in four birds may need to find new homes because of increased greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Under a 2C (3.6F) warming scenario, shifts in environmental suitability are projected for 70 per cent of bird species studied across summer and winter ranges. There will likely be a net loss of bird species in summer and a net gain in winter.

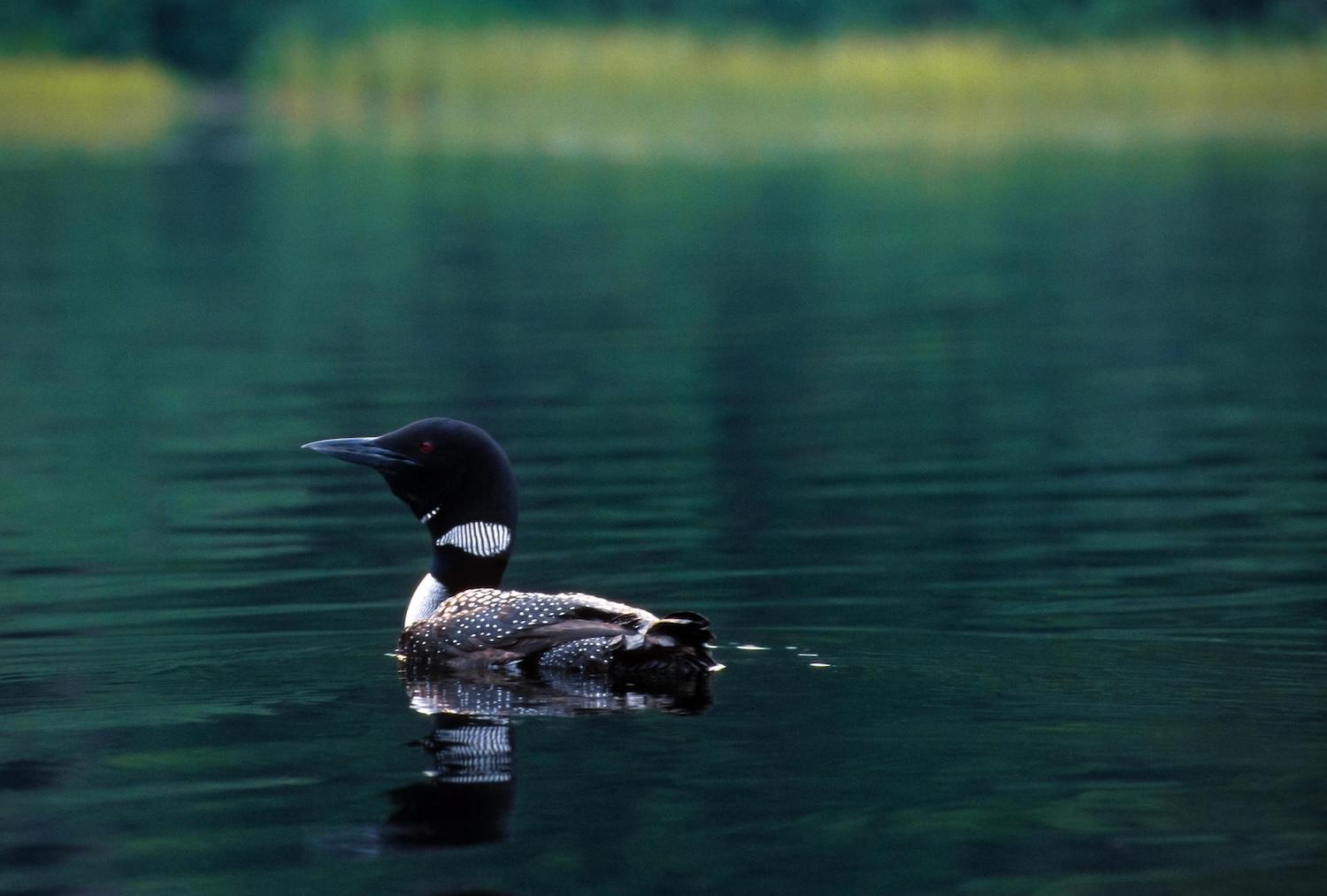

In Canada, the Common Loon could be driven north due to climate change/J. Pleau, Parks Canada

The study details how habitat suitability will either improve, worsen or remain stable for each species, and how birds may colonize new areas or become extirpated (locally extinct). Species that are highly specialized to a particular habitat — like grasslands and boreal forests — will have the hardest time adapting.

An icon that appears on the Canadian dollar coin (aka Loonie), the Common Loon could disappear from some parks in summer months as its range shifts northward. Canada Jays, once touted as the national bird, may disappear from southern boreal parks as their food stores decay from more freeze-thaw events.

Released in 2022, the Candian study was summarized into a report and made accessible on OpenGov in 2023. Briefs were then prepared for each park. “We classified the sites so they could begin to see how vulnerable they are,” says lead contributor Scott Parker, an Ontario-based Great Lakes ecosystem scientist for Parks Canada.

More freeze-thaw events are harming the Canada's Jay winter food supply/Wayne Lynch, Parks Canada

For Rouge, the 11-page brief looks at 115 of the 159 summer species, and 75 of the 110 winter ones. “Climate change is expected to alter the bird community at the park, with climate suitability projected to improve for some species and worsen for others,” it concludes.

For example, if global temperatures rise 2C (3.6F), things could improve for 18 species at Rouge in summer, remain stable for 55 and worsen for 12. That means 30 species now found here in the summer could potentially be extirpated.

“I think part of the message here is not feeling helpless or hopeless,” warns Parker. He urges people to upload observations to Seek by iNaturalist, Merlin Bird ID or eBird — “remarkable tools for connecting people with nature.”

Scott Parker, a Parks Canada ecosystem scientist, helped produce the study about birds and climate change in national parks/Parks Canada

People can also become citizen scientists during the Christmas Bird Count or other programs offered by Birds Canada like the Breeding Bird Survey or FeederWatch. Using window treatments and turning off lights at night to reduce window strikes, especially during migration, helps. So does planting native species in gardens and keeping cats inside (or at least leashing them or building “catios”).

Every “stepping stone” that we create helps birds get from protected place to protected place.

Back in that Rouge field looking for Bobolinks — a threatened songbird in the blackbird family that loves tall-grass prairie and makes do with hay fields and pastures— talk turns to how protected areas can be climate refuges for birds.

In an off-limit area of Rouge National Urban Park that attracts Bobolinks, Leonardo Cabrera sets up listening equipment/Jennifer Bain

Cabrera is leading a project that looks at how grassland birds distribute in parklands to validate a 2023 landscape connectivity model. A member of the Canadian Association of Sound Ecology, he co-leads a soundscape project that is collecting a baseline of acoustic signatures across the park.

“Once you start recording these sounds, basically you are sucking energy of the environment because sounds are energy,” explains Cabrera. “And when you have this energy already captured in a recording, you can actually explore it. You can play it back, you can forward, you can actually compare it to another time.”

Rouge staff have set up autonomous recording units and professional sound recording machines to capture bird activity during the breeding season between late May and mid-July. These self-contained audio recording devices are programmed to capture sounds at specific times, particularly at dawn and dusk when bird activity peaks. Without the need for human presence, there’s a stronger chance of recording rare, elusive and even dangerous wildlife.

It's hard to focus on bird sounds in the Bob Hunter Memorial Park area of Rouge National Urban Park because you'll be stepping on so many snails/Jennifer Bain

“What is the closest sound? What is the most distant? Are they interacting with each other,” Cabrera asks after we set out on foot from the Bob Hunter Memorial Park to look at an area that Parks Canada has restored.

To be honest, I'm fixated on the distant hum of traffic and the unpleasant crunch of all the snails that we step on along the paved path.

When Cabrera identifies the sound of two American Goldfinch likely competing for territory, I realize that my parents taught me to bird by sight and I never progressed beyond that. “I think it’s actually more important to identify by listening,” he says.

New signage welcomes Rouge National Urban Park visitors to its Bob Hunter Memorial Park area/Jennifer Bain

This area was once a farm field but it’s being restored with native grasses to promote a grasslands ecosystem. He stands proudly beside some big bluestem, a grass that grows up to seven feet high and provides important habitat for birds and other wildlife.

“As an ecologist, this is just beautiful,” Cabrera says. “It’s actually reproducing, it’s producing seeds, it’s fully developed.”

We drive to the 19th Avenue Day Use Area to admire a meadow that attracts Eastern Meadowlarks, a grasslands specialist. Instead we spot plenty of Savannah Sparrows, which also gravitate to grasslands with low vegetation, and Eastern Kingbirds that love open habitats.

A Savannah Sparrow enjoys the restored grasslands in Rouge National Urban Park in July/Jennifer Bain

I learn that fussy Bobolinks like medium-height vegetation that’s one to three years old and about up to my hip. Breeding pairs like 7.5 to 12 acres each and are becoming stressed as they have to share rapidly declining habitat.

Cabrera sets up his recording gear and listens.

“There is a harmony. There are different notes and they find their own acoustic space. They are actually just forming a symphony of sounds,” he observes. “The question is, how does this place sound like? How should it sound?”

In an area of Rouge National Urban Park known for Song Sparrows and the distant hum of traffic, Leonardo Cabrera takes a listen/Jennifer Bain

According to the climate change study, some of the species we hear now are likely to face challenges and maybe even disappear. The Bobolinks that were here in late May and early June are gone, possibly just migrating or quiety taking care of their fledglings. “This place is quieter now without them,” laments Cabrera.

It will be even quieter if they never return, but Parks Canada has pledged to keep this precious unmarked spot a grasslands ecosystem and, for now, off the radar of the public. “This is a big decision for us," Cabrera says, "because Parks Canada has said this is going to be this forever, and that implies actually doing something.”

An American Goldfinch flies overhead. A Mourning Dove sits motionless in a tree. The Bobolinks are either hiding or gone for the season. But as we return to our vehicle through a thick field of tall grass, there is reason for hope.

On the day I went birding in Rouge National Urban Park, the Eastern Kingbirds were out enjoying an open area of restored meadows/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment