Strolling San Francisco’s Financial District, I reach a sidewalk studded with dozens of nails. Curious, I read a plaque that describes the ship found buried beneath it, the General Harrison. Looking up, I see a ship hull sculpture embedded in the façade of the Club Quarters Hotel.

But this ship at Clay and Battery streets isn’t the only one in this district densely packed with high-rise office towers: it’s just the first I hear of the astonishing story of Gold Rush-era ships buried beneath my city, discovered during construction for new buildings. Up to about 70 buried ships are here, estimates Ron S. Filion, author of Buried Ships of San Francisco, a 2023 book about 180 Gold Rush ships, but no one knows for sure.

A block down on Clay, a plaque marks the spot where the Niantic, a ship later reborn as a warehouse, shops, and hotel, was found in 1978. Incongruously, it’s right by the Transamerica Pyramid, the city’s tallest building until 2018, separated from the triangular 853-foot tower by a redwood grove park.

The Arkansas, a few blocks away, became a bar in 1851: a hole was cut through its bow, and patrons entered by gangplank. (The Old Ship Saloon survives today.) Yet another ship, found when the city’s transit agency was digging a tunnel for its light-rail system, was too big and expensive to excavate beneath Justin Hermann Plaza, so it was left in place. (“Tell Greg we have sheep [ship] in tunnel,” a Russian-accented engineer radioed to his boss.) Astoundingly, passengers by the thousands travel through the hull of the Rome inside the tunnel under Justin Hermann Plaza, by the Ferry Building, the famous food hall marketplace and ferry terminal.

A "forest of masts" rose above San Francisco harbor in 1851/NPS file

All these ships are slumbering beneath city streets thanks to the gold rush that was ushered into California in 1848 in the Sierra Nevada foothills. People came from all over the world to the sleepy port of Yerba Buena (San Francisco’s original name) to strike it rich. Blinded by gold fever, passengers and crew abandoned their ships after a voyage of six to seven months from New York and around Cape Horn at South America’s tip. Almost 1,000 ships came in a few years, almost 800 from U.S. ports alone.

About 11,000 Australians emigrated to San Francisco from 1849-51, including about 7,500 from Sydney. They formed “Sydney Town,” a settlement at the southern base of Telegraph Hill, east of “Little Chile,” a settlement of Chileans, Peruvians and Mexicans. (Named for Chile’s port city, Valparaiso Street exists today.) About 20,000 Chinese came to San Francisco in 1852, and America’s oldest Chinatown began.

Some ships were converted to storage or temporary housing and dragged to shore. Others sank in the mud. Rising amid a forest of masts, San Francisco was “Venice built from pine instead of marble, a city of ships, piers and tides,” a Chilean journalist once called it, notes Richard Everett, the former exhibits curator at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. Settlers covered them with sand from abundant dunes and debris, as the town began selling “water lots” in the bay, on the condition buyers covered them with land. The town whose shoreline began at Montgomery Street was extended eight blocks or so inland.

“San Francisco happened almost as an accident of history,” says James Delgado, a maritime archaeologist for more than 40 years and author of Gold Rush Port: The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco’s Waterfront. “With 1848 and the discovery of gold, everybody was saying, ‘Here’s the lottery. I can win it!’ And so off they go.”

But the gold-seekers had no clue how distant the promised treasure lay, that they needed to go “30 miles up, and then get into the rivers… and then, once you get into Sacramento or Stockton, get into the foothills themselves,” he adds. After a major fire in May 1851, the boom town became “Gold Rush Pompeii.”

The hull of the Niantic after it was excavated in 1979/NPS file

Delgado credits seeing the William Gray, found in 1980 during construction for Levi’s Plaza (it remains today under the fountain) at Levi Strauss headquarters, as a young park ranger at the historical park, as life-changing.

“To actually walk the decks of the long-buried ship, to smell the bitter ashes of the fire that razed the town to the ground on May 4, to watch the tides wash around the pilings of the dock burned to the waterline and buried two stories below the sidewalks, to open casks of biscuits, crates of wine and sacks of coffee that had been sealed in the mud for nearly a century and a half — that has been magic, and inspired me to study the ships and docks that lie beneath modern San Francisco and tell their story,” says Delgado. In August, he helped locate the only U.S. Navy ship later used by Japan's Navy after its capture, the USS Stewart, off the Sonoma coast in Bodega Bay, as senior vice president of Search Inc., a private underwater recovery firm. He was the chief scientist on a Titanic excavation in 2010.

San Francisco’s most famous buried ship, the Niantic, first traded with China in the 1830s, bringing tea, silk, and porcelain to the United States. Later, it became a whaling ship. But while in Peru, Captain Henry Cleaveland of Martha’s Vineyard heard that thousands of people in Panama were chafing to sail to the California gold fields. So, he sold the whaling gear, bought 150 mules and timber, and sailed to Panama, where he found gold-seekers happy to pay for a mule ride instead of walking. After riding across the 50-mile-wide isthmus with his herd of mules to the Caribbean side, where the marketplace was (a week’s journey), Cleaveland sold the animals at a tidy profit to gold-seekers anxious to cross the country. (A railway was built later. The Panama Canal didn’t open until 1914). While waiting for the captain to return, his crew built cabins with the timber, then took on 249 paying passengers. Crew cooked their meals in iron whale blubber pots.

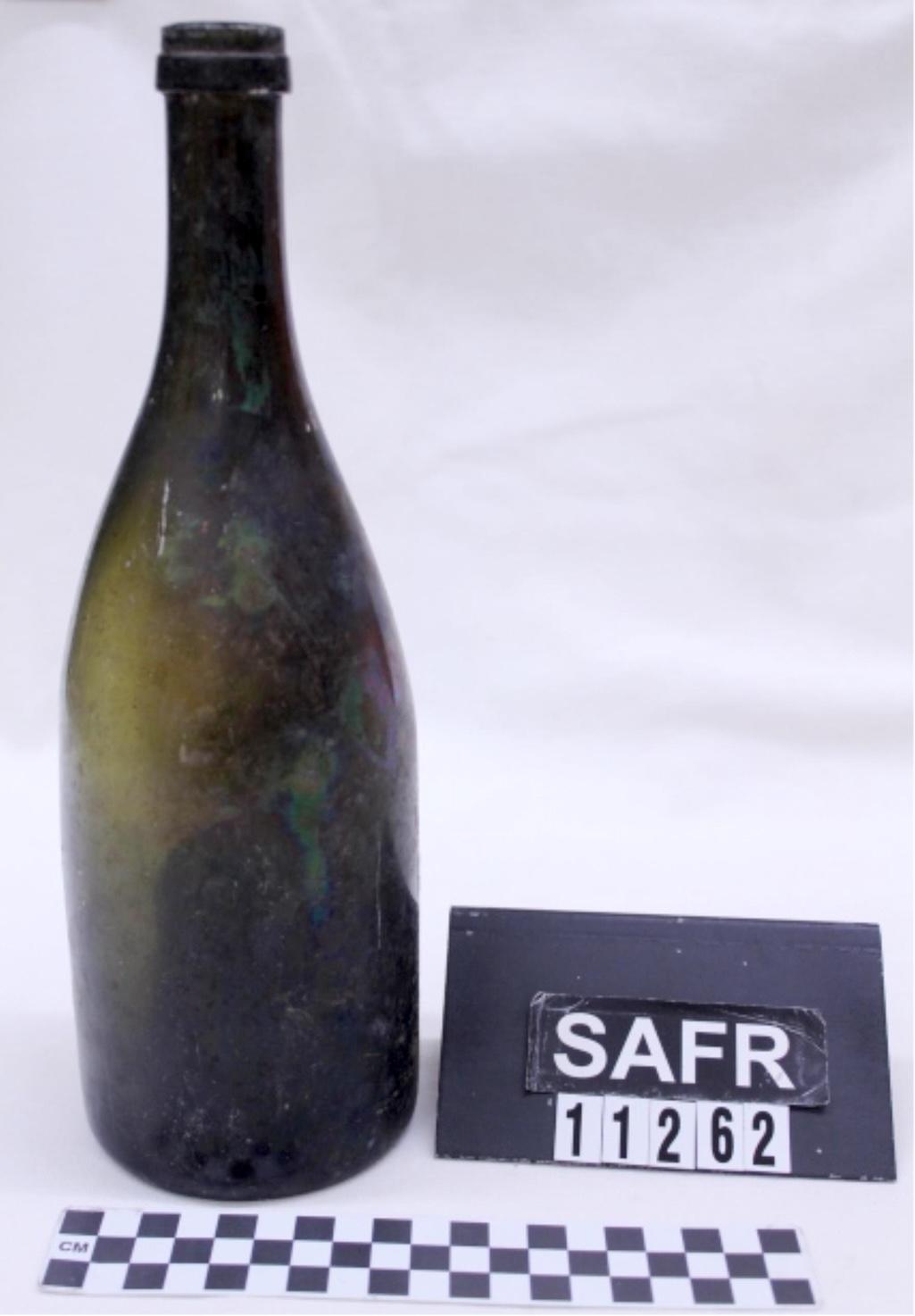

This champagne bottle was recovered from the Niantic's remains/NPS

When an irate passenger, convinced the captain was sailing in the wrong direction, challenged him to a duel, Cleaveland accepted, with one condition. As passengers worried if their ship would soon lack a captain, he coolly asked if he could choose his weapon. Told yes, he reached for his whaling harpoon.

“Needless to say, the passenger backed out,” Everett chuckles.

Upon arrival in San Francisco, the ever-enterprising captain sold the remaining lumber. He also sold the ship to some Chileans, who pulled it to shore. Covered by a shingled roof, the Niantic then had shops and offices on its deck, and a wide balcony. After the 1851 fire, everything was destroyed except its submerged hull, which became the foundation of the Hotel Niantic, which stood until 1872.

“The Niantic dig was more of a frantic rescue operation because the developers allowed the narrowest slot of time,” Everett says. “The dig was awful for everyone but served as a great catalyst to the city to make developers adhere to better standards and make the developers responsible for it.”

Many digs were led by Archeo-Tec, an Oakland archaeology firm. Today, a case of Niantic artifacts, such as a brass duckhead paperholder with red eyes, is in the historical park's visitor center, while its stern and rudder are in the park’s Maritime Museum. The museum, known for the West Coast’s greatest collection of maritime artifacts, is in a building in Aquatic Cove that, fittingly, resembles an ocean liner, designed in late Art Deco style.

Painting of the Niantic at sail/NPS

In contrast, when the General Harrison was discovered in 2001, “It stopped construction on the hotel for months while archaeologists sifted through the dig searching for artifacts,” says Heller Manus Architects spokesman Hao In Kuan. “We’ve had other ships found under our projects; it’s not unusual because so many ships were abandoned here.”

Some ships carried unusual cargo, as bones found with them show. Giant Galapagos Islands tortoises weighing 450-600 pounds were captured starting around 1849 and sold as a delicacy in San Francisco, sometimes at a price exceeding the value of the ship’s remaining cargo. Turtle steaks and soup were served at Venitian (sic) Restaurant and Florence Saloon, newspaper ads show. One schooner carried 580 tortoises in 1855. After eating nothing during the months-long voyage from Ecuador, tortoises were “enjoying themselves amazingly, and were grazing on the banks of the Sacramento River” near that city before being sold, a newspaper notes.

It’s best to ponder such quixotic history in the Old Ship Saloon, ideally over a Gold Rush bourbon cocktail or Pisco Punch, whose origin is the 1830s Peru trade. Most gold-hunters never became rich, but some who supplied goods to them did —‚like Levi Strauss, the German immigrant who manufactured sturdy work pants from blue denim. But their ghosts may be cheered to know they’re immortalized in 180 sidewalk medallions on the Barbary Coast Trail (the waterfront’s nickname, when it was the wildest and rowdiest in the West.), as well as the name of our city’s football team, the 49ers.

Sharon McDonnell is an award-winning travel, culture, food/drink and profiles writer in San Francisco, published in Conde Nast Traveler, Food & Wine, Architectural Digest, Next Avenue, AARP, Fodors.com, Teatime, Travel & Leisure, CNN Travel, Business Insider, PUNCH, Dallas Morning News, and The Telegraph (UK).

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places