Hurricane Helene diminished the forest canopy and caused massive damage along the famous treadway, which already faces major environmental concerns.

In the dozen years since Doug Levin began volunteering with the Mount Rogers Appalachian Trail Club in southwestern Virginia, he has spent more time working on the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in November and December 2024 than he has at any other time. As the longtime trail supervisor for the club, he has been managing and working alongside teams of sawyers clearing downed trees and debris from the trail in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

A Category 4 hurricane at its peak, Helene tore through the Southeast in late September, causing hundreds of billions of dollars in damage across a vast region. The storm brought tropical-force winds and flooding to the southern Appalachian Mountains, impacting towns and cities as well as national park units, including Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway.

But impacts were also significant and unprecedented along hundreds of miles of the Appalachian Trail —“the most destructive natural disaster the century-old trail had seen,” according to The New York Times— adding to ongoing concerns about invasive species, pollution, and habitat loss and forest fragmentation that have plagued the trail landscape for years. Scientists predict that potentially more than 17 million acres of forestland in the Southeast, including areas around the A.T., might be lost by 2060.

“We deal with downed trees, erosion, drainage issues, shelters, privies, and normal damage all the time,” Levin says. “The different thing about this storm was the sheer quantity of everything—trees down, damage to the trail by large root balls by trees upended, and more.”

Crews spent the fall clearing trees along the A.T., including on Mount Rogers in Virginia/ATC

A Methodical Process

Conceived in 1921 and completed in 1937, the A.T. stretches for about 2,190 miles between Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Maine. A popular destination for both day hikers and thru-hikers, the trail passes through 14 states, encompassing a diversity of experiences, viewsheds, forests, meadows, and mountain towns.

The A.T. is managed collaboratively between the National Park Service and the nonprofit Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), which itself coordinates and provides oversight to the more than 30 trail clubs, such as the Mount Rogers club, that provide on-the-ground maintenance and stewardship.

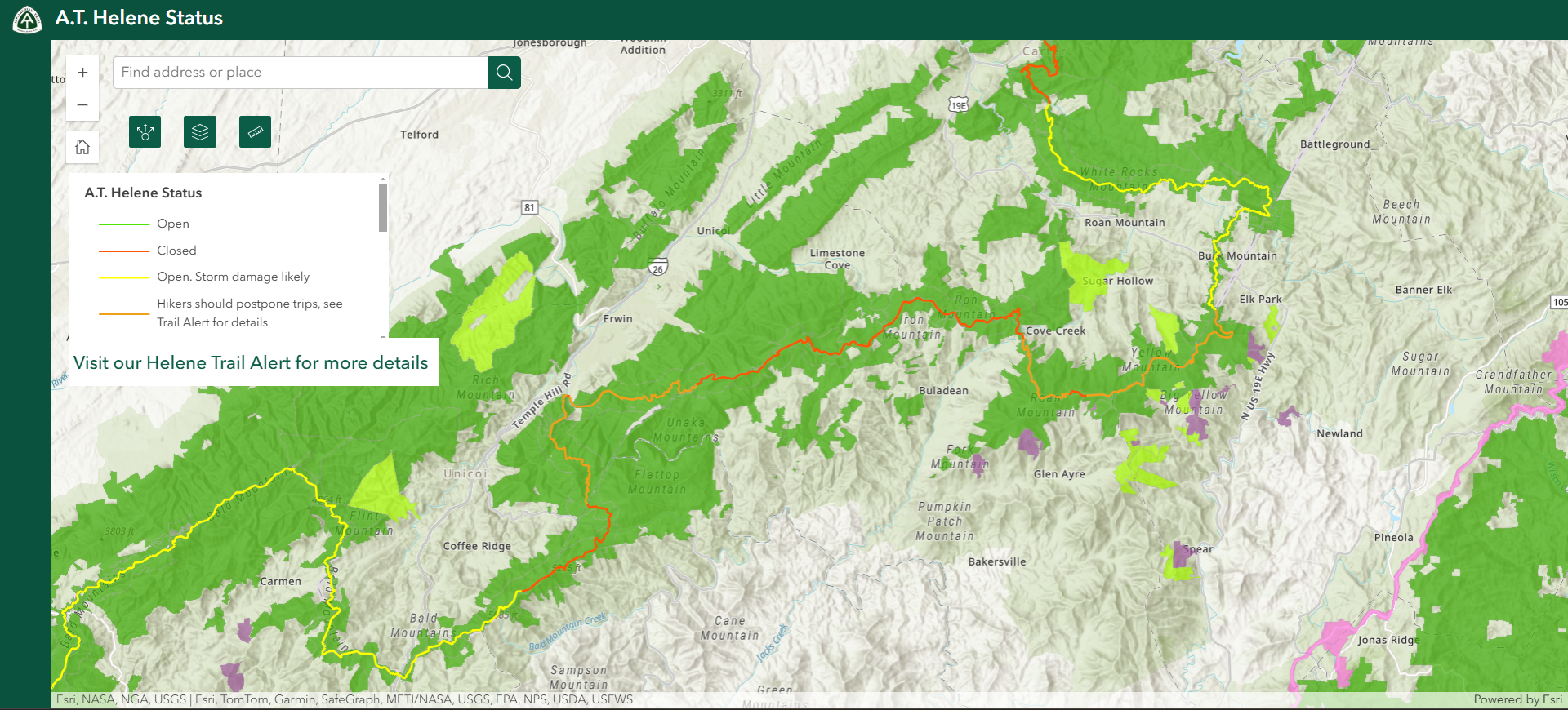

Immediately after the storm, it was difficult for teams to get onto the trail to determine the extent of the damage. Trail managers naturally assumed that the southern third of the A.T. would be the most severely impacted, but after more assessment, they determined that the most damaged sections are along a 400-mile expanse between Interstate 40 in North Carolina and Tennessee north through Pearlsburg, Virginia, close to the West Virginia border.

“When we talk about the 400-mile stretch, there's different levels of impact,” says Dan Ryan, ATC’s vice president of conservation and government relations. “Some areas have been impacted so severely that the public land agencies, in this case, the U.S. Forest Service primarily, have actually closed those stretches just because of primarily blowdowns. In some cases, they're 20- or 30-foot [tall] downed trees, and safety is of the utmost concern.”

As of this week, 111 miles of the A.T. remained completely closed. Damage is significant in several areas, including to trail shelters and the complete wash-out of at least one bridge—the Chestoa Bridge over the Nolichucky River in Erwin, Tennessee, at mile 344.6. (Video footage of the bridge washing out is dramatic and harrowing.)

A screenshot of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy's map of Helene-related closures along the A.T. as of late December / ATC

By far, however, the primary challenge facing trail managers is clearing downed trees, which have been so significant in some areas that holes have opened in the canopy and some familiar viewsheds have changed.

“Even finding the trail has been difficult in some places,” says Ryan, “much less cutting the trees out to assess the treadway itself. So, at this point in time, the big challenge is clearing out these trees that are on the ground in order to even evaluate what the trail looks like, to see if it's been washed out. It’s a methodical process.”

For now, ATC has been encouraging hikers to avoid closed and damaged areas and to be flexible and mindful about their 2025 plans. Although most thru-hikers are “northbounders” who start in Georgia, it might be beneficial for 2025 thru-hikers to either start in Maine and head south or at a halfway point like Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, going north and then finish the southern half of the AT later.

“Hikers are going to have to be aware of where they set up camp, and be aware if it's really windy or if there's been a recent storm,” says Ann Simonelli, ATC’s director of communications. “We’re asking hikers to pack flexibility and patience.”

Ecosystem Concerns

Just as hikers will have to adapt to these changed conditions, so will the ecosystem itself.

Over the longer term, conservationists and trail managers are concerned about how Helene’s disruption to the tree canopy and widespread flooding will impact crucial wildlife habitat and foster invasive species. Scientists have found that, generally, invasive species are less negatively affected by extreme weather events, in part because they tend to have high reproductive rates and adaptive physiologies. Spotted lanternfly, emerald ash borer, garlic mustard, and Japanese barberry are just a few of the invasive insects and plants found along the trail.

“Without a tree canopy, you kind of restart the process of what we call habitat succession,” Ryan says. “Another challenge here is that all of that downed wood will likely remain except in areas that are deemed really just excessive or creating a wildfire hazard. But in some cases we would like for that fuel to be removed to the extent that we can start a restoration process if it's applicable to that certain area…to kind of jumpstart the succession process.”

With so much damage and exposed root balls from down trees, it’s “the wild west for invasive species,” Ryan adds. “From a biodiversity conservation perspective, being able to manage those invasive species while we're restoring the native habitats is a big strategy for us. But if the downed trees are there, you can't even access areas to do that, and that's a real challenge. ”

A section of trail in the Unaka range in the Cherokee National Forest in North Carolina/ATC

Steps Forward

Along the A.T. near Mount Rogers, Levin worked alongside volunteer and professional sawyers to clear the trail of Helene-related debris, including workers from across Virginia, the New River Gorge in West Virginia, and elsewhere. The work was particularly grueling and tricky in areas of the trail that are federally designated as wilderness because power tools are not allowed in such places.

“Those portions had to be cleared with hand tools,” Levin explains. “The total person hours that were applied in a three- to four-mile stretch of wilderness was almost 350 hours, using cross-cut saws.”

Normally, the trail club takes a break from working on the trail in the winter, but given the enormity of the clean-up, Levin says they will assess opportunities to work if the ground isn’t too frozen and the weather is amenable.

“On the ground, the trail would not exist without the volunteer trail clubs,” Levin says. “That’s something that all of us should appreciate. There’s plenty of opportunity for people to help. We have had more interest over the past couple months from people. The A.T. is something that has to be maintained for a long time.”

If silver linings exist, the folks at ATC hope that Helene has raised concern and awareness about the Appalachian Trail and its significance as a cultural and historic resource and a recreation destination.

“It’s looking positive that both the U.S. Forest Service and the Appalachian Trail office of the National Park Service will receive hopefully some supplemental [federal] funding to address infrastructure, to address habitat,” Ryan says. “So we’re trying to find the silver linings and aligning opportunity with funding and with our strategies that may have had a lot longer runway than they do now.”

Whether the A.T.’s many stewards can bolster these vital landscapes before the next major storm hits, however, remains an open question.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places