If you were a 5,000-pound elephant seal looking for a place to haul yourself up from the depths of the Pacific to rest your flippers for a bit, Drakes Beach at Point Reyes National Seashore in Northern California is a good place start.

A long crescent of soft, golden sand on the leeward side of Point Reyes, the beach sweeps up to the foot of erratic sandstone cliffs. The point is really a giant peninsula that juts out into the Pacific at a southeasterly angle, forested in the highlands with tidal marshes and beaches at the shoreline. The San Andreas Fault runs right through the eastern side of the point, with portions of it filled by the waters of oyster-rich Tomales Bay.

Drake’s Beach faces due south, which shelters the sandy expanse from the worst of the winter storms that pound the peninsula’s exposed western shores. The waters of Drake’s Beach are generally calm, with only the occasional jolt of significant wave energy disrupting an otherwise tranquil scene.

Well, tranquil except when the elephant seals are there.

During the winter breeding season there can be well over 2,000 of these bellowing, fighting, galumphing marine mammals on the beach. Occasionally, the seals slink their way across beachside parking lots, prompting closures and funny social media posts from Point Reyes rangers.

There’s a visitor’s center nearby that is occasionally closed because the more aggressive seals do not take kindly to being approached. Which is apparently impossible for many tourists to the national seashore to avoid.

But here’s the thing: the elephant seals aren’t really supposed to be there. Or at least they weren’t, historically speaking. They only began showing up in significant numbers at Drake’s Beach in about 1995, according to National Park Service biologist Sarah Codde.

Elephant seals used to migrate to the small beaches on the western shores of Point Reyes each winter to breed, not bothering with the long swim around the point to the calmer waters of Drake’s Beach.

“By 2019, they’d pretty taken over almost the entire stretch of Drake’s Beach,” says Codde.

Elephant seals on Drake's Beach / NPS

The small beaches the seals used to visit, located at the foot of tall cliffs with only a dozen or so yards of accessible sand, are disappearing. Frequently big and damaging waves and ever higher tides have claimed much of the beaches once favored by the elephant seals. There’s been a constant decline in the amount of seals that still breed on those dwindling scraps of sand. They’ve been forced to find new breeding grounds, ones less susceptible to encroaching tides and punishing surf.

The culprit? Climate change that’s causing bigger and more frequent winter storms, for one. And moving slowly but surely, the inexorable creep of rising sea levels. Parts of Point Reyes National Seashore are gradually disappearing as the ocean behaves in ways not seen in millennia. In this case, it’s not a canary that’s sounding the rising sea level alarm with a chirp. It’s van-sized, roar-grunting elephant seals.

The Inexorable Rise Of The Seas

Sea level rise isn’t just a potential threat. Researchers know it’s happening, and we’re learning more about why it’s happening all the time.

Scientists can tell the historical pattern of sea level rise by looking at historic tide gauges where possible, and from things like sediment and ice cores from around the world that show where high water marks have been in millennia past.

Interestingly, how and why sea level rises has shifted in recent decades, though the root cause has remained largely the same. According to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the planet’s temperature has risen roughly 2°F since 1880, with the ocean’s temperature in turn rising 1.5°F. Water expands as it warms, and that expansion was generally the cause of sea level rise until recently.

Now, however, it’s melting sea ice, largely from Greenland ice sheets, that’s driving global sea level rise.

“The sea level rise we see today is about two-thirds from melting ice, and one-third from thermal expansion,” says Sean Vitousek, a U.S. Geological Survey oceanographer.

And it’s accelerating.

According to several 2016 studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sea level is rising faster than it has in the previous 2,000 years.

"This isn't a model,” said Benjamin Horton, a Rutgers University geologist who led one of the studies, in emphasizing that rapid rising isn’t a “what if” scenario. “This is data.”

It’s historically been difficult to predict which areas around the world are likely to see the most sea level rise, but modern satellite imagery has given researchers a much clearer picture of the changes and potential threats to come. That includes the ability to predict where sea level rise will have the greatest impacts.

Now, there are even tools like NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer, an online interactive map that allows anyone to visualize what different levels of inundation might look like anywhere in the world. And that visualization is grounded in hard science about how different areas are likely to respond to rising seas.

Screenshot of NOAA Sea Level Rise Viewer

“Every meter of sea level rise means 50 meters of beach retreat,” notes Vitousek.

Dan Reineman, an oceanographer at California’s Channel Islands State University, charts what that amount of retreat means for public coastal access, which of course includes national parks.

“In California, every foot of sea level rise corresponds to a loss of about 100 coastal access points,” he says. That means things like stairways to beaches, parking areas in low-lying coastal areas, and simply beaches themselves will be inundated. ”These results highlight that not only are California's beaches highly susceptible to rising sea levels, but our ability to visit and enjoy beaches is also at risk.”

Erosion And Habitat Loss

It’s often national park units on the East Coast that get the headlines about impacts from sea level rise. Everglades National Park, for example, is already seeing seawater intruding into inland areas, according to the NPS. Half of the park may be completely underwater by 2100.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore on the Outer Banks of North Carolina is seeing increased beach erosion from rising seas. Houses are famously falling into the Atlantic Ocean there as the water creeps ever so insistently inland, reshaping coastlines and consuming entire stretches of public beaches. Much of that is due to bathymetry. The East Coast has a shallow continental shelf, compared with the West Coast, so rising seas will have a particularly obvious impact on coastal national parks there.

“The most vulnerable sites for sea level rise are eroding, sandy beaches and low-lying elevations,” says Vitousek.

That pretty much describes all of the Eastern Seaboard. But the West Coast is also firmly in the crosshairs of rising seas. Southern California, has, in some ways, a miniature version of the East Coast’s bathymetry, with a relatively shallow continental shelf, and is poised to suffer a great deal of beach loss as the seas rise.

In fact, a 2015 study released by the Department of Interior estimated that damage to national park infrastructure and cultural resources from sea level rise could total a whopping $40 billion nationwide.

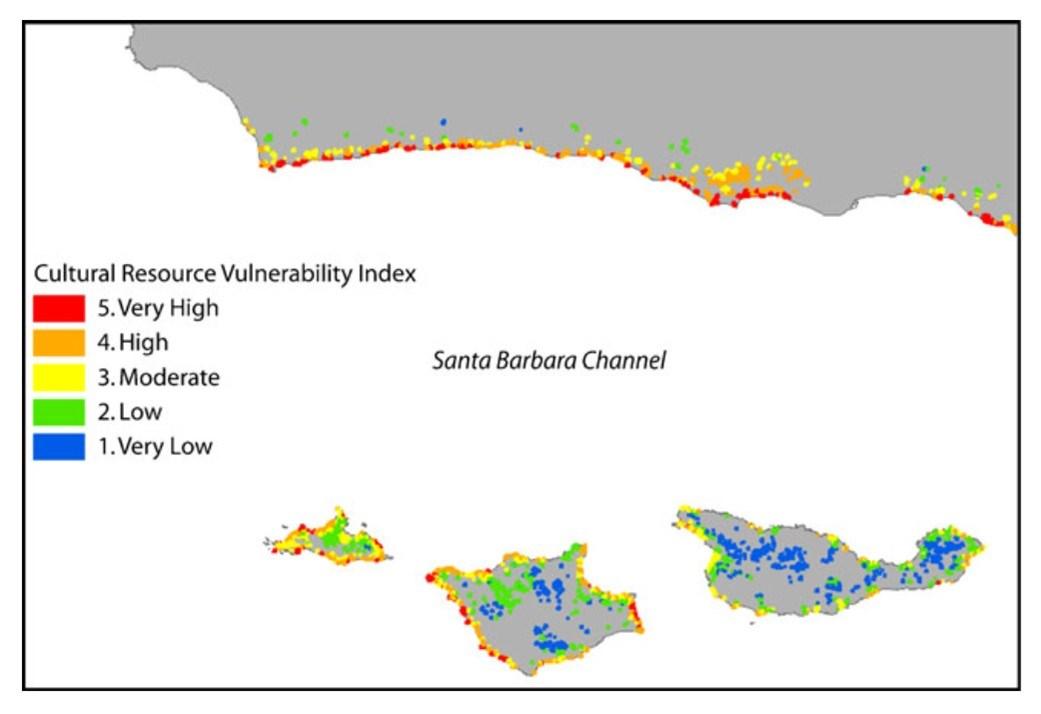

Channel Islands National Park is composed of five of the eight islands that make up the Channels Islands group offshore of the California coast, due south of Santa Barbara. They’re mostly uninhabited now, but historically were home to Chumash and Tongva/Gabrieleño peoples. Most of the islands’ land is well above any potential threat of inundation by rising sea levels, but the areas that are threatened — low-lying beaches — are also the places where people have accessed the islands for thousands of years. It’s where you’d haul your canoe to shore today if you paddled to one of the islands in the park, and it’s where the Indigenous populations did too.

Archaeological sites along those beaches are, therefore, in danger of being inundated and lost forever.

Sea level rise impacts to cultural resources on the Channel Islands and Santa Barbara coast / NPS

Rising seas also have the potential to reshape life in the rocky, intertidal zones of the islands at the foot of steep cliffs, home to thousands of species of marine animals and plants. In the coming decades, these areas of swirling, nutrient-rich water flowing in and out as the tides change, will creep higher up the rocks, with the marine life matching pace to remain at the water line. “A ‘crunch’ may occur where organisms run out of shoreline in which to shift, potentially reducing the abundance and diversity of those intertidal communities,” says the NPS. According to researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Channel Islands may also see loss of crucial eelgrass habitat, as well as fewer areas for sea birds to nest and breed.

In short, a very different experience for future visitors to the national park. Not to mention the life that depends on a stable ecosystem there.

But of course, it’s not just Southern California that will feel the effects.

As you move further north along the west coast, the continental shelf begins to steepen and drop away, but areas with flat sandy beaches at the foot of tall, rocky cliffs are already feeling the effects of rising seas. And, in places like Point Reyes, just like at Channel Islands National Park, those effects are claiming the habitat of protected marine life, and, increasingly, public access to national park seashores.

Now, each winter, waves at Point Reyes encroach ever further up beaches once home to elephant seals, stripping away the sand and eliminating a place for the behemoths to breed. Even at Drake’s Beach, which is increasingly becoming a kind of last stand for the seals.

“I’ve seen entire sections of Drake’s Beach washed away during storms, exposing the bedrock beneath,” Codde says. “It’s been pretty shocking to me.

“Continued climate change could raise sea level on the Pacific Coast enough to inundate most suitable habitat for northern elephant seals in Point Reyes National Seashore by 2100.”

Dave Press, another wildlife biologist at Point Reyes, points out that the Snowy plover, a diminutive shorebird protected under the Endangered Species Act, is also threatened by sea level rise. The little birds nest on flat beaches, exactly the kinds of beaches being reclaimed by the sea.

“We’ve seen areas that have had nesting plovers in the past that have seen total erosion,” Press says.

One of the most important stretches of nesting habitat for the Snowy plover is a flat isthmus of sand called Limantour Spit, just to the east of Drake’s Beach. It’s one of the most popular draws to Point Reyes National Seashore, with families flocking to the soft yellow sands every weekend. As the seas rise, the very existence of Limantour starts to come into question.

“I can imagine a future where the entire spit is submerged under high tides,” Press says, with some resignation.

Looking southeast down Limantour Beach at sunset / NPS

Nowhere Is Immune

North of Point Reyes, other national parks are reckoning with ever higher tides too.

Redwood National Park, near the California-Oregon border, is rugged and wet, with dripping, impenetrable redwood forests pressed against the cold, wild Pacific. Rocky beaches with thin strips of sand dot the more than 40 miles of the park’s coastline. Those beaches, like ones in Point Reyes and at the Channel Islands, are susceptible to being scoured from the face of the Earth.

Incredibly, sea level rise around Redwood National Park must contend with the fact that the land itself is rising above the sea, because of plate tectonics. The Gorda plate, a small offshore tectonic plate is sliding under the North American plate in Northern California. This pushes the land up ever so slightly each year. Yet, the sea rises faster. NOAA projections show that by 2050, intermediate high tides at Redwood NP beaches will be 1.21 feet higher than they are today. By 2100, that figure jumps to an astonishing 4.72 feet.

Already, coastal bluffs at the park are being eroded. More than three feet, in some places, since 2007. The ancestral coastal village of Shin-yvslh-sri~, perched on a sandy overlook, a place of deep cultural importance for the Indigenous Tolowa people, is in danger of eroding away.

Like at the Channel Islands, intertidal marine life at Redwoods will have to adapt to deeper in-shore waters, or face being wiped out. The Thomas H. Kuchel Visitor Center, the park’s popular focus for education and administration, is in danger of being wiped out by higher tides and bigger waves.

Further north still, Olympic National Park, on Washington’s verdant Olympic Peninsula, is facing many of the same issues. According to a report issued by the Environmental Protection Agency and the NPS, rising sea levels threaten to swamp important cultural resources (petroglyphs), inundate sensitive intertidal marine life habitat, erode cliffs beneath park roads, and damage park utilities. Backcountry campsites along the west coast of Olympic in coastal wilderness zones, as well as the popular Pacific Northwest Trail, are also vulnerable to sea level rise.

The changes feel slow, the higher water lines barely perceptible. But changes are coming, faster than we’d like.

What to Save?

So what can be done?

Well, nothing about the rising seas. Even if no more carbon was belched into the atmosphere today, the heat already in the oceans will continue to melt sea ice. That ship has sailed. But there are some ways to at least mitigate some of the damage. One of the easiest, and most effective is already underway at Point Reyes.

“Native dune habitats historically existed much further inland than they do now,” says Press. “We know we can restore dune habitats to provide a buffer.”

By removing invasive species like iceplant and European beach grass, ecologists at Point Reyes are able to expand habitat for nesting Snowy plovers. So, as the seas claim some beaches, there’s room for the little birds to spread inland.

“We’ve already restored 271 acres of dunes,” Press says. “We’re essentially creating a respite for the plovers in a time of climate change.”

Park infrastructure must also adapt. At Point Reyes, trails down by the water are getting “blown out,” Press says. Cliffside erosion means the loss of public access to beaches. Much of Point Reyes is managed as a wilderness area, and as rising seas and erosion claim more land, officials there have to decide if it’s worth trying to save access.

“We struggle with the idea of rebuilding,” the biologist says. “We’re trying to be better about managing wilderness areas. When winter storms destroy trails, we have to ask, ‘do we rebuild those?’

“In more and more cases,” Press continues, “we’re just going to close trails.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places