Uh-oh, this doesn’t look good. A kayaker is careening down the narrow winding river, letting the current pull her towards danger instead of paddling like mad away from it. “Stay hard right,” shouts Hailey Albers. “Stay away from that root wad.” Whooping and hollering, the woman rather gleefully crashes right into a partially submerged tangle of tree roots.

“Lean towards the tree,” Albers calmly urges.

“Why can’t my husband pull me like he said he would,” laughs the good sport, freeing her kayak and breezing past us towards calmer waters.

Buffalo National River etiquette means lending a hand when other boaters run into trouble, like at this gnarly tree root/Jennifer Bain

I’ve come to Arkansas to float one of the last free-flowing rivers in the lower 48 states. The first time I visited the Buffalo National River it was fall and there wasn’t enough water left here in the Upper District to launch a canoe or kayak. This time it’s spring break and America’s first national river is low but floatable.

I’m daytripping from Bentonville to explore the seven-mile stretch between Pruitt Landing and Hasty Access. It should take four to five hours, depending on the water level and how many times we hit snags, capsize, take breaks or stop to gawk at the Ozark Mountains.

“You might see some gar. Smallmouth (bass), maybe. Might be some turtles out today,” predicts Jon Trublood, the river manager for the Buffalo Outdoor Center (BOC).

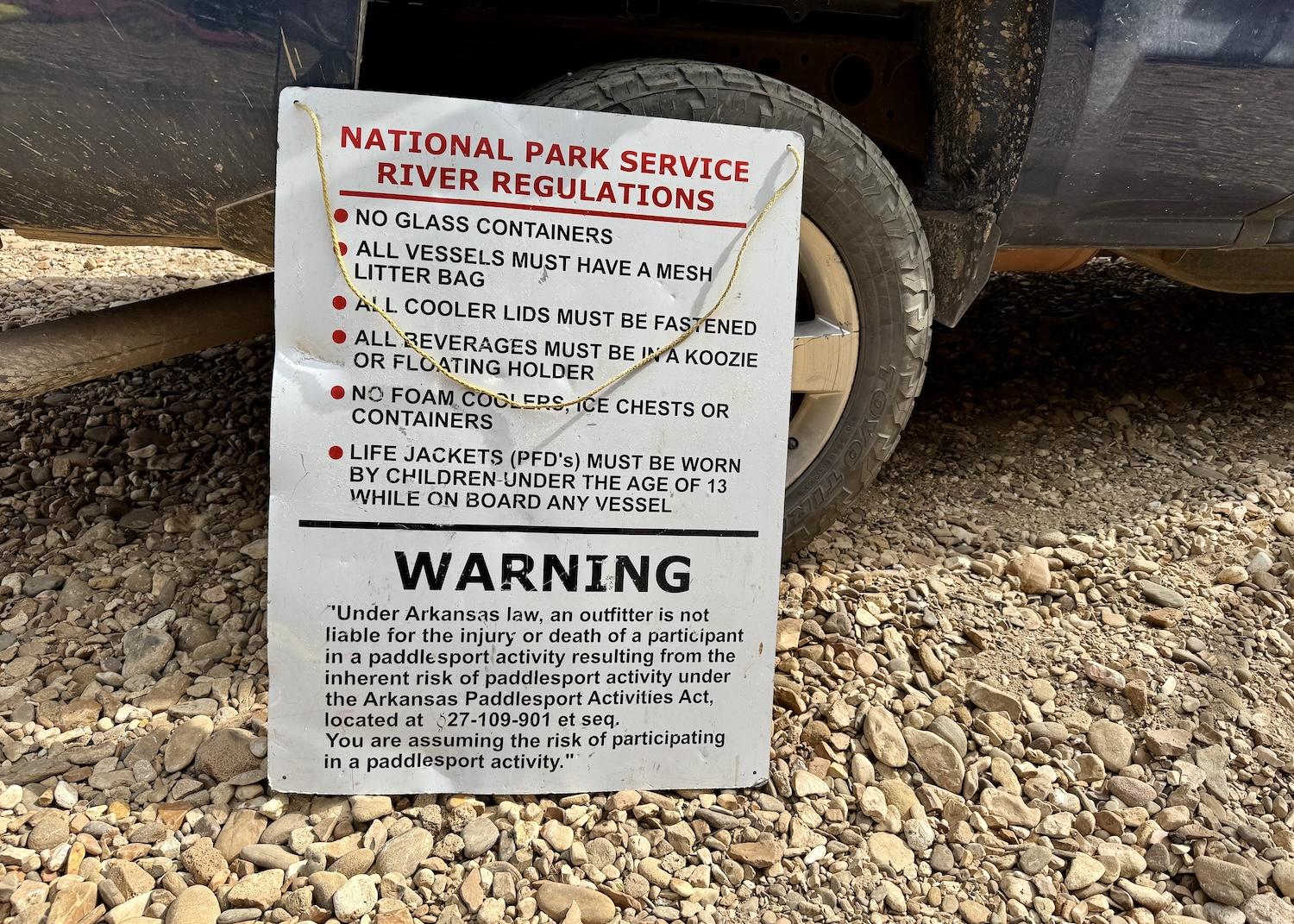

The National Park Service has rules for people floating the Buffalo National River/Jennifer Bain

This part of the Buffalo is rated as a Class I/II river that’s suitable for most paddling skill levels except when the water is high. It’s fairly low today — “a nice, laidback, easygoing stretch of river,” Trublood promises. Well, except for that “big old root wad sticking out of the water about head high” an hour downriver on river left.

“If the current tries to take you right to that tree, you’ve got plenty of room on the right side to get through there,” he advises. “It just gets really shallow. You may have to step out but you won’t have to carry the boat. Maybe just leave it in the water. Take 10, 15 steps, hop back in. Other than that, it should be pretty clear. You folks have a great time out there.”

How could you not have a great time on this “alluvial meandering river” (more on that in a moment) that became a national river in 1972 after a grassroots movement to stop the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from building a dam.

On a spring day, kayakers and canoers set off from Pruitt Landing to float the Buffalo National River to Hasty/Jennifer Bain

The river begins as a trickle in the Boston Mountains and flows north and then east through the Ozark Mountains until it merges with the White River. The National Park Service oversees 135 of the Buffalo's 151 miles. The park’s 94,293 acres are actually divided into three management districts — the Upper, Middle and Lower Districts. People come to float, swim and fish, but also to hike on 100 miles of trails and ride on designated horseback riding trails. In the Upper District, float trip season typically runs March to June.

Last year, the Buffalo drew nearly 1.7 million visitors, a number that has been steadily climbing since the pandemic and that has skyrocketed from 13,200 in 1973.

The first hour of floating is uneventful, just a turtle here and a snake there sunning themselves on logs and rocks. Dumb luck gets me past the gnarly tree, so I stop on a gravel bar and wait for my friends to catch up. One fellow has capsized and lost his Ray-Bans. Someone else searching for it finds a GoPro — what Albers calls "river booty." Anyway, I lose track of how many people paddle by, some screaming with delight and others shrieking in fear.

Buffalo National River boaters must "pack in and pack out" to keep the pristine wilderness free of trash/Jennifer Bain

“Try to stay hard right,” Albers shouts to several kayakers when we all gather on the gravel bar for packed lunches. “Awesome job. That one’s a tricky one right there — y’all survived.”

“Thanks for your coaching,” a grateful man replies.

“It’s a tricky one. It’s gotten a lot of people,” allows Hailey. Her dad, Mike Mills, fell in love with the Buffalo decades ago. He went from renting out canoes and guiding trips along it to buying land just outside the park, building cabins, growing his business to a year-round operation, and building his dream home in the mountains above Ponca.

The Buffalo National River always looks different depending on whether the water is high or low. This gravel bar/lunch spot emerges when the water level is low/Jennifer Bain

Hailey (the company’s “director of first impressions”), her husband Austin (the president) and young son River guide five of us (an Arkansan, Canadian, Swede, Brit and German) on a float trip.

Over sandwiches on the gravel bar, talk turns to how the NPS is finally developing a new river management plan — just the second since the park began more than 50 years ago.

“The plan will identify strategies to address changing visitation patterns, increasing interest in commercial services, impacts on cultural and natural resources, and the implications of climate change on both visitor use and resource management,” the NPS said in a 2024 news release.

The park service wants to learn what makes the Buffalo so special to so many. For Austin, it’s “the turquoise color of the water, the bluff lines, the waterfalls and the beauty” of the natural, flowing river.

The Buffalo National River has turquoise water in certain places thanks to the presence of limestone/Jennifer Bain

The NPS also hopes to hear what’s interfering with desired experiences and what people envision for the Buffalo's future. Key issues include river resource impacts and river health, diminished visitor experience attributable to crowding and safety concerns, and river access and associated infrastructure. As Austin explains, the infrastructure here hasn't kept up with the times, and while the cap on rental boats on the river hasn't changed since the 1970s, the number of people who bring their boats (especially kayaks) has exploded.

A 30-day public comment is complete. A draft plan is in the works and the NPS has promised to share an update during public meetings by summer, but the park doesn't respond to my email request for an update. It lost rangers in the recent federal downsizing upheaval and the seasonal visitor contact station by the Steel Creek Campground is shuttered on the Thursday that I visit.

The final river management plan is slated to be ready by next summer.

People love to float the Buffalo National River, which is known for its striking bluffs and turquoise water/Jennifer Bain

One thing the plan won’t do, though, is “address or propose a change in designation” from national river to national park and preserve — that would have to be done through Congressional action.

A few years back, some people got together and quietly started studying whether it would make sense to mimic how West Virginia’s New River Gorge National River became New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, a move that usually brings more funding. But when that independent background work — that had nothing to do with the NPS — became public knowledge during 2023 phone surveys, people were furious and feared a government land grab.

“It was like every wild story that you could come up with is what came out,” remembers Austin, “and it got twisted every way except what the actual truth was.”

One kayaker dodges the treacherous tree root while another gets snagged on it and has to abandon her water-filled boat/Jennifer Bain

Our illuminating lunch chat is constantly interrupted by boaters who need help navigating what young River dubs “Mr. Bad Tree Stump.” Since this is a national park, nobody can tie an orange safety flag to the hazard to make it more visible.

“Okay, left, left,” one canoiest tells his family but he's so chill you just know it's not going to end well.

“Lift your paddle — it’s not even in the water,” his furious wife snarls at their teenage son. “If you’re going to steer in the back you have to have it in the water.”

The angry words hang in the air. “This is how you test your marriage,” whispers Austin, shaking his head. “You did great,” Hailey shouts to ease the tension and we quietly hope things turn around for this unhappy family.

The Eastern Redbud blooms in March along a calm, shallow stretch of the Buffalo National River/Jennifer Bain

Mostly because it's the right thing to do, and perhaps because there's no cell service out here, people always help each other out on floats.

“Dad, can you take me over there to that stump,” asks River, who has been taking videos of the hazard to share with the river manager. “I want to direct people.”

“No," Austin replies, "because if they hit it, they’re going to knock you in the water.”

“If they come towards me, I’ll just push them away,” the boy counters to no avail.

A snake (probably a copperhead) suns itself on a rock along the Buffalo National River in March/Jennifer Bain

Anyway, it’s time to pack up our lunch trash and move on down this alluvial meandering river. That’s a fancy way of saying that the Buffalo doesn’t flow over bedrock, but as the NPS explains over a “nice cushion of gravel, sand and rocks that keeps the bedrock intact.” It also meanders with wide curves and less steep surroundings.

We don’t wind up spotting any Alligator gar (the largest fish species in Arkansas) but there are plenty of turtles and snakes out sunning themselves, countless "buzzards" (technically turkey vultures or black vultures) overhead and even a couple of Canada geese foraging for aquatic food. The shallow river is mostly clear, sometimes murky and occasionally turquoise.

The Buffalo cuts through sandstones, limestone, dolostone and limestone. Limestone is composed primarily of calcium carbonate and is white. “As the river breaks down this rock into tiny crystals,” the NPS explains in a Facebook post (the best place these days to hear from rangers), “these crystals will get mixed up into the water. When sunlight hits the tiny crystals, it will reflect that beautiful blue color.”

There's a gorgeous bluff at the end of the Pruitt Landing to Hasty Access float/Jennifer Bain

Somehow I miss Welch Bluff and the visible geologic fault line that captivated American painter Thomas Hart Benton who loved floating and painting Ozark rivers. The "Big Bridge" appears too soon. It's the only thing made by humans instead of Mother Nature that we've seen and a sign that the takeout spot on river right is fast approaching.

We pull our kayaks up on a sandy beach, admire Chimney Rock Bluff, then climb a steep and well-worn path to the parking lot where our driver awaits. Most people have paid extra to have their vehicles shuttled here while they paddled. It's about a 25-minute drive between Pruitt Landing and Hasty Access, but we've taken four hours and 10 minutes to cover that same route by water.

There's no drama at the end of this trip down America's first national river, just happy floaters grateful for their Ozark adventures, root wads and all.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places