Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Shaul Hurwitz, research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Yellowstone National Park is famous for its volcanic landscapes, erupting geysers, colorful hot springs, and abundant and diverse wildlife. The park is also unique because of the many waterfalls along its rivers and creeks that mostly form in deep gorges, where rocks with differences in hardness meet or at the edges of thick rhyolite lava flows.

“After gathering a sufficient supply of water, they commence wearing their channels down into the volcanic rocks, which continue to grow deeper as they descend. Each one has its water-fall, which would fill an artist with enthusiasm.” So wrote Ferdinand V. Hayden, who explored Yellowstone starting in 1871 (Hayden report of 1872, p. 75).

Yellowstone National Park abounds in waterfalls. But how do they form, and why are there so many in the Yellowstone region?

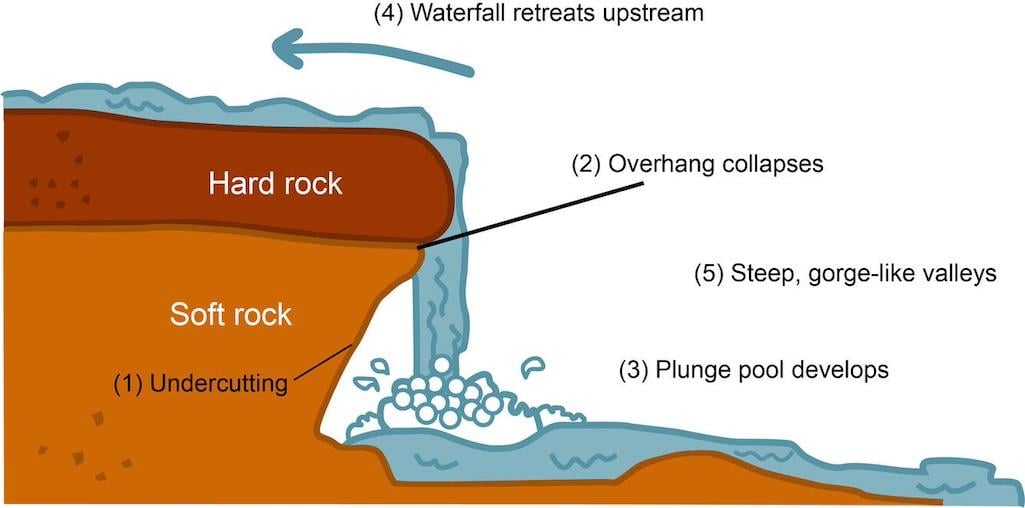

Although there are several definitions for a waterfall, a common one is “a very steep commonly vertical fall of some magnitude in a river course”. Various clas¬sifications of waterfalls were developed based on their origin and characteris¬tics, such as height and rock type. The most common model to explain waterfall formation suggests that they form where rock units with different hardness meet laterally or vertically. If a stream flows over harder rocks that are more resistant to erosion than the rocks immediately downstream, a ledge or bench will form across the streambed because the softer and less resistant rocks are worn away faster. As the ledge becomes higher, the softer downstream rocks will erode faster. This undercutting of the less-resistant rock causes the overhanging rock to shear off, and typically a plunge pool at the base of a waterfall is created where the water impacts.

Schematic illustration of waterfall formation in which a hard rock that is more resistant to erosion is atop a softer rock that is less resistant to erosion. Source: Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WaterfallCreationDiagram.svg).

The highest waterfall in the world is Angel Falls in Venezuela (3,212 feet, or 979 meters), and in the United States it is Oloʻupena Falls on the Island of Molokai in Hawaii (2,953 feet, or 900 meters). There are 52 sites In UNESCO’s World Heritage List with waterfalls, of which three are in the United States (in Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and Yosemite National Parks). A USGS dataset and a US Fish and Wildlife Service waterfall database contain information about waterfalls and rapids for the continental United States.

The rivers flowing in Yellowstone National Park are fed by large volumes of water from snow and rain falling over the Yellowstone Plateau. Many stretches of these rivers are nearly flat bottomed, but in some sections the rivers contain narrow valleys where deep gorges were carved. Some waterfalls in Yellowstone formed where rocks with differences in hardness meet in these deep gorges, while others formed at the edges of thick rhyolite lava flows. There are approximately 350 waterfalls of more than 15 feet in the park. Many of these can be viewed by hiking a short distance, for example, Gibbon Falls near Madison Junction, Tower Falls near Tower Junction, Mystic Falls near Biscuit Basin, and Fairy Falls near Grand Prismatic Spring (the latter named by Colonel Barlow, who explored the Yellowstone region 1871 and 1872, “from the graceful beauty with which the little stream dropped down a clear descent of 250 feet” (Hayden report of 1872, p.112).

Photo of Fairy Falls in the Lower Geyser Basin, near Grand Prismatic Spring/NPS, Jacob W. Frank, October 28, 2018.

There are two prominent waterfalls in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone: the Upper (33 meters, or 109 feet) and the Lower Falls (94 meters, or 308 feet). The Lower Falls is the tallest waterfall in the park and is significantly taller that the total height of Niagara Falls (51 meters, or 167 feet for the Canadian and American Falls). The Upper and Lower Falls can be viewed from several locations along the rim of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

Like many prominent waterfalls, those in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone exist because rock layers change laterally from soft to hard. At the end of the last glacial period, about 14,000 years ago, ice dams at the mouth of Yellowstone Lake failed, and the large volumes of water that were released caused massive floods downstream. These floods led to erosion of the present-day canyon, which is a classic, narrow, V-shaped valley, indicative of erosion by rivers rather than by glaciation (which tends to form broad, U-shaped valleys). The canyon is approximately 24 miles (39 kilometers) long, and its depth is between 800 and 1,200 feet (240 and 370 meters). The thick rhyolite flows at the base of the canyon were hydrothermally altered and weakened by hot groundwater. After the canyon formed, the weakened rhyolite was less resistant to flow of the Yellowstone River downstream from the falls.

A large number of impressive waterfalls are in Yellowstone's southwest corner, which is unofficially named the "Cascade Corner" as a result. Snow accumulation in this area is the highest across the Yellowstone Plateau, and most of the rivers and creeks mainly drain the Pitchstone Plateau, the site of the last volcanic eruption in Yellowstone. To see some of these remote waterfalls requires long hikes. In the Bechler River drainage, these include Colonnade (67 feet, or 20 meters), Albright (260 feet, or 79 m), and Ouzel (230 feet, or 70 meters) Falls. Bechler River was named after Gustavus Bechler, a surveyor and cartographer with the 1872 expedition led by Ferdinand Hayden, and Albright Falls was named after Horace Albright, an assistant and acting director of the National Park Service and later superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. Some other notable waterfalls in the “Cascade Corner” include Silver Scarf (250 feet, or 76 meters) and Dunanda (150 feet, or 46 meters) Falls along Boundary Creek, and Union Falls (250 feet, or 76 m) on Mountain Ash Creek.

Photo of Colonnade Falls on the Bechler River in southwest Yellowstone National Park, also called the “Cascade corner”/NPS, Diane Renkin, September 15, 2012.

When planning a visit to explore Yellowstone National Park’s many wonders, consider taking the time to view some of its many waterfalls. Perhaps you might be able to identify different rocks on either side of the waterfall, or perhaps see the edge of a thick rhyolite lava flow. If you are adventurous and ready to visit the park’s backcountry (having obtained the necessary permit, of course), you will be rewarded by many waterfalls with significantly fewer people. In the "Cascade Corner," where the annual precipitation is more than 50 inches (about 130 centimeters), you will be challenged by many stream crossings and a pesky mosquito population in the early summer months. Most hikes in that area start at the Bechler ranger station trailhead.

Additional Reading:

- The Guide to Yellowstone Waterfalls and Their Discovery (2000) by Paul Rubinstein, Lee H. Whittlesey, Mike Stevens

- Waterfalls of Yellowstone National Park by Charles W. Maynard (1996)

- Ribbons of Water: The Waterfalls and Cascades of Yellowstone National Park (1984) by John Barber

- Goudie, A.S., 2020. Waterfalls: forms, distribution, processes and rates of recession. Quaestiones Geographicae, 39, 59-77.

- Final Sculpting of the Landscape based on The geologic story of Yellowstone National park by William R. Keefer, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1347, 1971

- Wikipedia sites: List of waterfalls in Yellowstone National Park, Yellowstone River Falls, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and List of world’s waterfalls by height

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places