To be honest, I have no clue what I’m looking at beyond the fact that it’s a key object in the World War II-era race to develop the world’s first atomic weapons before Nazi Germany. There is a giant wall full of holes that reminds me of a Lite-Brite toy, mannequin men with rods and a legend that talks about donut, iodine and uranium fuel slugs.

“Caution,” a yellow warning sign reads. “Check with the reactor operations department BEFORE opening any hole in the reactor at any time.”

I’ve come to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a highly secure multi-program research facility in East Tennessee, to see how the Manhattan Project National Historical Park conveys the story of America’s top-secret race to create the first nuclear bomb.

At the X-10 Graphic Reactor at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Chief Communications Officer David Keim talks to writer Jennifer Bain/Ray Smith

Los Alamos, New Mexico may have gotten all the attention in the 2023 historical thriller Oppenheimer, but the “Secret City” of Oak Ridge enriched uranium for use in Little Boy, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Three separate uranium enrichment technologies were pursued here while a pilot reactor and chemical separation plant also produced some plutonium.

The X-10 Graphite Reactor — the world’s first plutonium-production reactor — operated from 1943 to 1963 and the building is now a National Historic Landmark. It’s only accessible on guided tours, usually seasonal public bus tours that U.S. citizens (not foreign nationals like me) can take through the U.S. Department of Energy, but this stop is on hold due to nearby demolition work and so I come in as carefully vetted media.

“It’s amazing to me that it doesn’t look more space age,” concedes ORNL’s Chief Communications Officer David Keim as we admire X-10.

If you luck into a guided tour of the X-10 Graphite Reactor, expect benches in front of the famous reactor, a mammoth wall chart of the elements and isotopes, and a small interpretive exhibit/Jennifer Bain

The engineered reactor consists of large block of graphite surrounded by concrete and pierced by 1,248 horizontal channels. Workers once inserted uranium control rods into the channels and circulated cooling air around them. Irradiated rods fell from the back through a chute and into a water-cooled bucket. Inside the reactor, neutrons released from uranium fission transformed uranium-238 into plutonium.

The world’s first continuously operating nuclear reactor, X-10 went into operation (aka “went critical”) on Nov. 4, 1943, produced the first significant amounts of plutonium, and served as a proof of concept for the B Reactor at Hanford, Washington. It supplied Los Alamos scientists with the experimental quantities of plutonium needed to design Fat Man, the world’s first plutonium-fueled atomic bomb used in war.

The control room at the X-10 Graphite Reactor, a National Historic Landmark, can be viewed on public tours/Jennifer Bain

After the war, X-10 did things like produce radioisotopes. Today, you are allowed to see the reactor face and control room plus a museum nook filled with interpretive panels.

“Everything we do here traces in some way back to this reactor,” says Keim.

Before leaving the ORNL campus, I get to see Frontier (an exascale supercomputer that helps scientists to develop new technologies for energy, medicine and materials) and the Spallation Neutron Source (that provides the most intense pulsed neutron beams in the world for scientific research and industrial development). Don't ask me to explain either.

Three of the original gate houses to get into restricted parts of Oak Ridge are still intact, like this Bear Creek Checking Station on the way to the Y-12 National Security Complex/Jennifer Bain

I’m drawn here — after time in Townsend to explore nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park — because of two important anniversaries. The 80th anniversary of the end of World War II is in August. The 10th anniversary of the creation of Manhattan Project National Historical Park (with units in Oak Ridge, Los Alamos and Hanford) is in November.

Stop picturing national parks with entrance gates and clear geographic boundaries. The Oak Ridge unit alone has dozens of sites and only a few have direct ties to the NPS. The story unfolds in DOE research facilities like ORNL but also in museums and luxury assisted living facilities for seniors, outside modest historic homes, in restaurants that have taken over war-era buildings, and in front of 22 interpretive panels scattered across the city.

City of Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith shows me around. The retired historian for the Y-12 National Security Complex (a job he created during his 47 years there) is a photographer, author, filmmaker and tour guide who's also an “authorized visitor services provider” for the NPS.

Besides being home to the Oak Ridge Boys, Oak Ridge was one of three top-secret spots for the Manhattan Project. Historian Ray Smith stands by the Historic Grove Theater and a mural showing photographer Ed Westcott/Jennifer

“I’m very confident that I have the Oak Ridge portion of the story understood and — for the most part — documented,” says Smith over lunch at the Soup Kitchen in a former Manhattan Project-era bowling alley. “You cannot hire what I’m doing. You can’t point to a person and say I’m going to give you X amount of dollars, you go be passionate. It just don’t work that way. I do it because I love it, because I want to do it, because I enjoy it. And I think it is vitally important to be done and done well.”

Oak Ridge is now a government town of 34,000 dotted with nuclear-themed street names like Oppenheimer Way and Centrifuge Way. It’s a pleasure to take Smith’s guided tour, especially since the Manhattan Project superintendent cancels our meeting on short notice.

I don’t get to dig into how the NPS manages this unique park with the DOE, but from its foundation document, I know that the agencies collaborate to develop “partnership arrangements and other strategies to tell the complete story of the Manhattan Project and its legacy.” The NPS provides administration, interpretation, education and technical assistance. The DOE handles the management, operations, maintenance, access and historic preservation activities of the historic sites it controls.

This NPS desk in the lobby of the Children's Museum of Oak Ridge serves as the park's Oak Ridge Visitor Center. It is sometimes staffed by rangers/Jennifer Bain

Before I meet Smith, I stop at the NPS-run Oak Ridge Visitor Center. But with no park rangers on duty at what turns out to be a desk in the entrance of the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge, I help myself to park cancellation stamps, a junior ranger book, visitor guide and list of interpretive panels.

“A visit to the Manhattan Project National Historical Park will be different from a visit to many other national parks,” the NPS fold-out map warns. There are seasonal ranger-led walking tours and retro tennis court dances, but today I make do with an oversized map (like the kind big city hotels hand out) directing people to 13 places around town, starting with this museum.

I pay the museum fee, wander down the “Difficult Decisions Hallway” and start learning about people like Ed Westcott, the fellow who landed a dream gig when he was 20 as official photographer of the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge (aka Atomic City or Secret City).

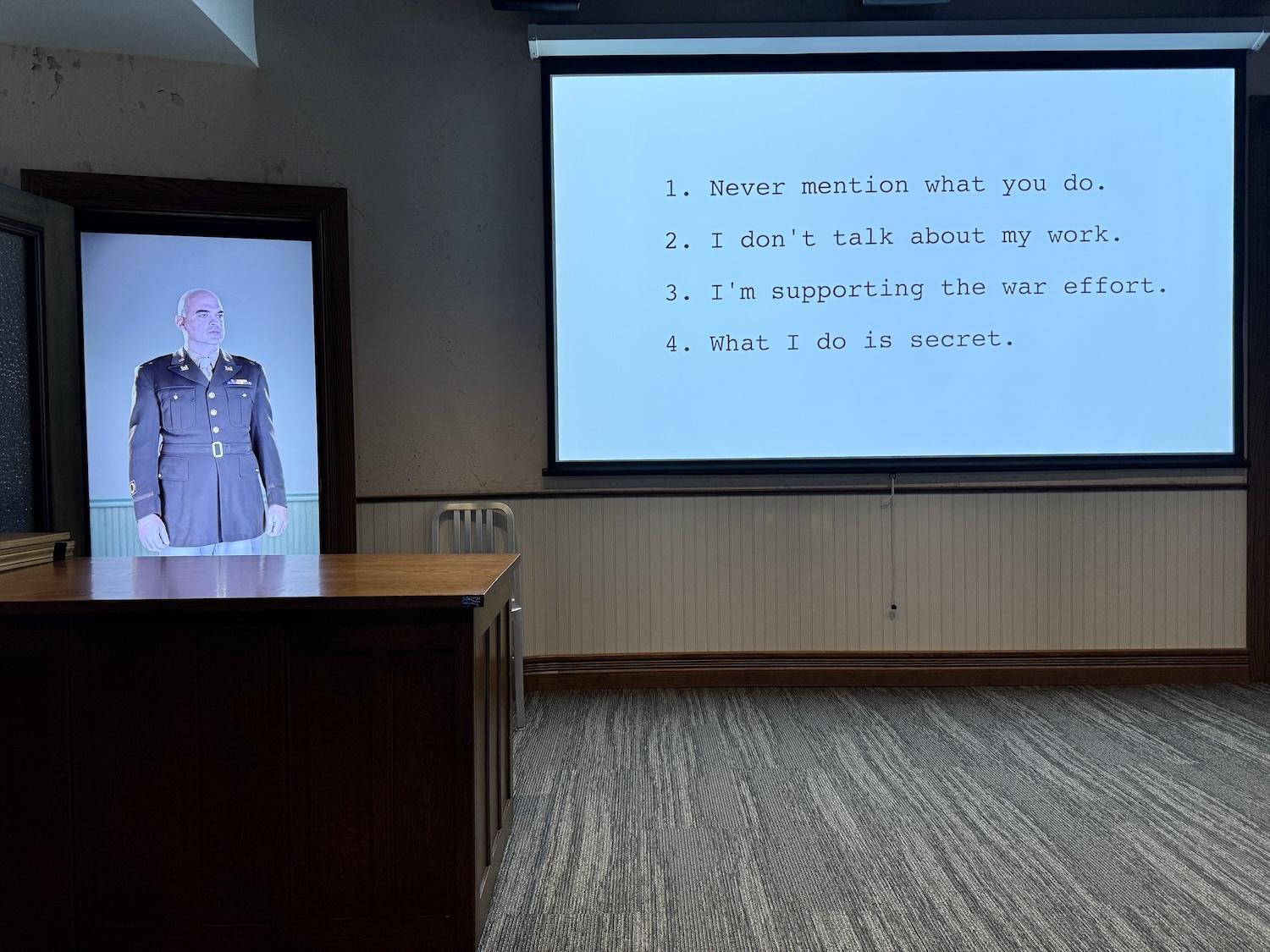

At the K-25 History Center, a short film speaks to the secrecy of Oak Ridge during the Manhattan Project in the 1940s/Jennifer Bain

Junior Ranger books do a great job of simplifying complicated stories. This one asks kids things like why the Manhattan Project was developed, what workers did that was so secretive and what Secret City elementary school is now a children’s museum. “There were seven gates to enter the Secret City and residents had to wear identification badges,” it notes. “How would you feel living behind a fence?”

When locals lobbied for a decade to get this park created, Smith got to tell Congress why it was so important. “Children are interested in history well told and the park service is the best way to tell our history most effectively,” he testified.

The Manhattan Project story starts in 1938 Berlin when chemists split the uranium atom, causing Albert Einstein to urge the U.S. to develop the fission bomb before Germany did. The Army Corps of Engineers quickly established the secret Manhattan Engineer District, headed by Brigadier General Leslie Groves, in Manhattan.

The NPS visitor center desk is in the Children's Museum of Oak Ridge inside what was once a Manhattan Project-era elementary school/Jennifer Bain

The government then used eminent domain authorities to acquire three rural sites in three states, displacing Tribes, farmers and homesteaders. Clinton Engineer Works (later renamed Oak Ridge) was built to enrich uranium and serve as project headquarters. The purpose-built city topped 75,000 people and boasted theaters, stores, schools, hospitals, parks, shops, public transit, a giant community swimming pool and more.

People knew they were helping with the war effort, but very few knew the true purpose of their work. “What you see here, what you do here, what you hear here,” billboards from that era warned. “When you leave here, let it stay here.”

World War II ended soon after the U.S. dropped the uranium-fueled Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on Aug. 6, 1945 and the plutonium-fueled Fat Man bomb on Nagasaki three days later.

There is a replica of Little Boy, the nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima during World War II, at the New Hope Visitor Center at the Y-12 National Security Complex/Jennifer Bain

“Anywhere in the world that you go and you say the word Oak Ridge, you’re going to immediately cause them to think about the atomic bomb. But we are so much more than the uranium for Little Boy,” insists Smith. “Nuclear medicine is the most significant contribution Oak Ridge has made to the world. There’s nuclear navy and nuclear power and right now the governor has put $65 million into forming a nuclear renaissance committee.”

On the pop culture front, he says “the Oppenheimer movie only mentions Oak Ridge two times, and Tennessee once, but it doubled the tourism in Oak Ridge.”

Irish actor Cillian Murphy won an Oscar for playing J. Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist and director of the Los Alamos Laboratory. But when I pop into the Alexander Guest House, I instantly recognize the famous Ed Westcott photo of the real Oppenheimer on the fireplace mantle. Once the only hotel for visiting scientists, dignitaries and workers, this building is now a posh assisted living facility for seniors.

The public can pop into Alexander Guest House to see where the most famous photo of J. Robert Oppenheimer was shot. Here the fireplace mantle at the assisted living home for seniors is decorated for St. Patrick's Day/Jennifer Bain

“This is where the famous photo of Oppenheimer was made in 1946,” says Smith. “Ed made it and that makes it important. The fact that it is a good portrait of Oppenheimer I think helps. We know exactly where the picture was made. We know the date, we know when and we know who made it.”

He chuckles remembering how a woman from the DOE Office of Classification once fretted that this black-and-white portrait should be hidden from the public, not because Oppenheimer was smoking or because it inadvertently revealed secret information, but because the handsome scientist's “sexy” eyes made it too sensitive.

It’s a photograph I see again at the Oak Ridge History Museum, which is housed in a Manhattan Project-era community center and is raising money for a much-needed Westcott statue.

The 44-acre footprint of what was once the K-25 Diffusion Plant is part of the Oak Ridge unit of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, but a new viewing platform is being built by another agency/Jennifer Bain

As well as X-10, the official NPS sites noted in the foundation document include Y-12 and K-25. I can’t get clearance to see Buildings 9731 and 9204-3 at the Y-12 National Security Complex where the electromagnetic separation method for uranium enrichment was pioneered and where weapons-grade uranium is still produced and stored.

But within Y-12’s New Hope Center, I do get to visit the Y-12 History Center, see a Little Boy replica and learn about the “Calutron Girls.” Originally known as cubicle operators, these mostly young women operated the control panels of the calutrons (mass spectrometers) that separated uranium isotopes. I'm warnted not to take photos between the parking lot and building.

Then it’s on to the 44-acre footprint of what was once K-25 Diffusion Plant. Construction is wrapping up for a K-25 Viewing Platform that’s funded by the Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management. “This whole area, the East Tennessee Technology Park, is going to be a major piece of the nuclear renaissance I believe is coming,” predicts Smith after we tour the K-25 History Center.

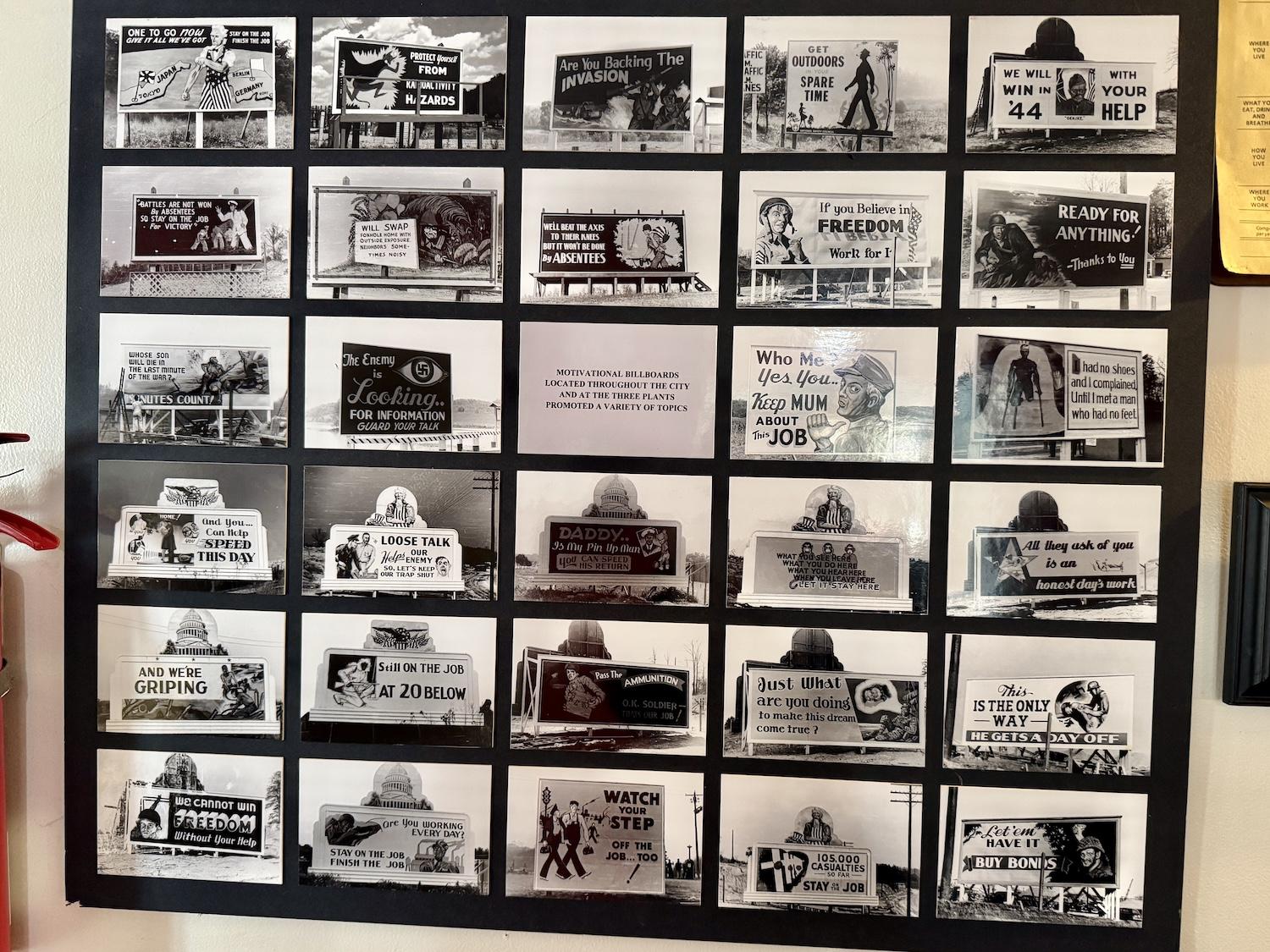

Edward Dougherty did the Manhattan Project's security billboards. This collection of photographs of his work hangs in the Soup Kitchen restaurant and at other spots around town/Jennifer Bain

I’m captivated by several vintage outdoor security billboards outside K-25. One shows a sniper and Oak Ridge worker that says: “Are you working every day? Stay on the job. Finish the job.” Another shows a wide-eyed man saying: “Who Me? Yes You…Keep MUM about this JOB.”

They’re the work of high school teacher Edward Dougherty who became the Manhattan Project’s sign painter and illustrator after being deemed too old for military service at age 35. The Oak Ridge Public Library maintains the Edward Dougherty Collection (photos of his billboards and signs) and says the artist later maintained more than 100 billboards for the American Museum of Atomic Energy.

Oak Ridge historian/tour guide Ray Smith loves the Jefferson Soda Fountain where you can order Y-12 Breakfast Bombs and K-25 Atomic Samplers. A NPS wayside out front provides insight into the historic Jefferson Shopping Center/Jennifer Bain

Now called the American Museum of Science and Energy, that modern, interactive space dives into the Manhattan Project and even mentions the national historical park. Smith also gets me a sneak peek of the Oak Ridge Associated Universities' Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity, acknowledging “we still, to this day, have people that live in Nashville that will not spend the night in Oak Ridge.”

There’s talk of placing NPS signs on the interstate to let more people know the Manhattan Project unit quietly exists, but Smith isn't sure that Oak Ridge is ready.

“Great Smoky Mountains National Park gets 14 million visitors a year,” he muses. “If we could draw a small percentage of that traffic, we would need to have something happening every day.”

The Manhattan Project National Historical Site Oak Ridge Visitor Center desk is only staffed five days a week/Jennifer Bain

The Manhattan Project may be considered “a secret that saved the world," but the atomic bombs that ended a brutal war also killed more than 200,000 people and raised ethical and moral questions among scientists and civilians.

That’s why I must see the International Friendship Bell. Designed in Oak Ridge and cast in Kyoto after local couple Dr. Ram Uppuluri and his wife Shigeko came up with the idea for "Project Peace Bell," this bronze beauty weighs 8,300 pounds and is nearly seven feet tall and five feet wide.

"The bell was built to honor the workers of the Manhattan Project, to commermorate the 50th birthday of Oak Ridge, and to become a symbol and everlasting monument for the peace," Shigeko is quoted as saying on a NPS wayside. "I feel something very special about this town, the town borne of war, living for peace and growing through science.”

Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith, an expert on the Manhattan Project, studies images on the International Friendship Bell/Jennifer Bain

The national park uses the bell to commemorate the Aug. 6 anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing.

Just before dawn each year, rangers light luminaries decorated with community messages of peace. People are invited to ring the bell “for whatever reason speaks to them” — reasons like lives lost, service, sacrifice and peace. But the bell is in a public park and you're free to ring it whenever you like.

With a suspended wooden striker, I do just that before Smith takes a turn and we stand quietly, lost in our private thoughts about war and peace, until the gentle humming ends.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places